2024 Seger Grant Report: Paths to Urban Growth in the Nineveh Plain: Survey at Tell ‘Arna

Khaled Abu Jayyab, University of Toronto

The Paths to Urban Growth in the Nineveh Plain project (PUG) established in 2023 aims to understand proto-urban developments and population aggregation that took place in northern Iraq during late prehistory. The efforts of this project include exploring past assumptions about trajectories towards complexity through targeted excavations at Tepe Gawra and Tell ‘Arna, and carrying out a regional survey in collaboration with our partners at the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH).

Work at Tell ‘Arna, facilitated in part by the generous contribution of ASOR’s Joe D. Seger Project Grant, allowed for a team from the University of Toronto led by Khaled Abu Jayyab in collaboration with the Mosul office of the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH) to carry out a systematic survey of Tell ‘Arna located in the eastern Mosul Suburb of Gogjeli (Fig. 1).

Survey work at the site proved to be an important step towards establishing an accurate periodization of the site and streamlining our approach to future excavations, protection, and conservation work at Tell ‘Arna.

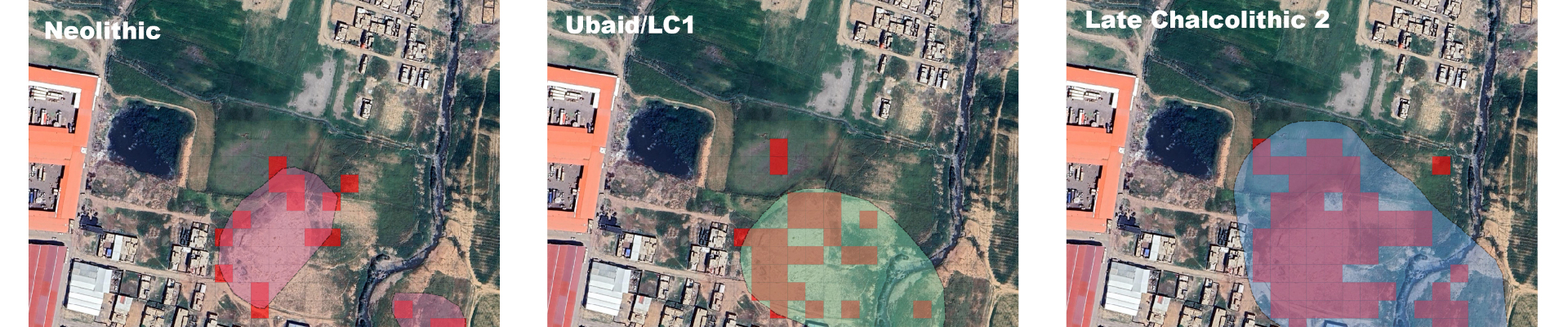

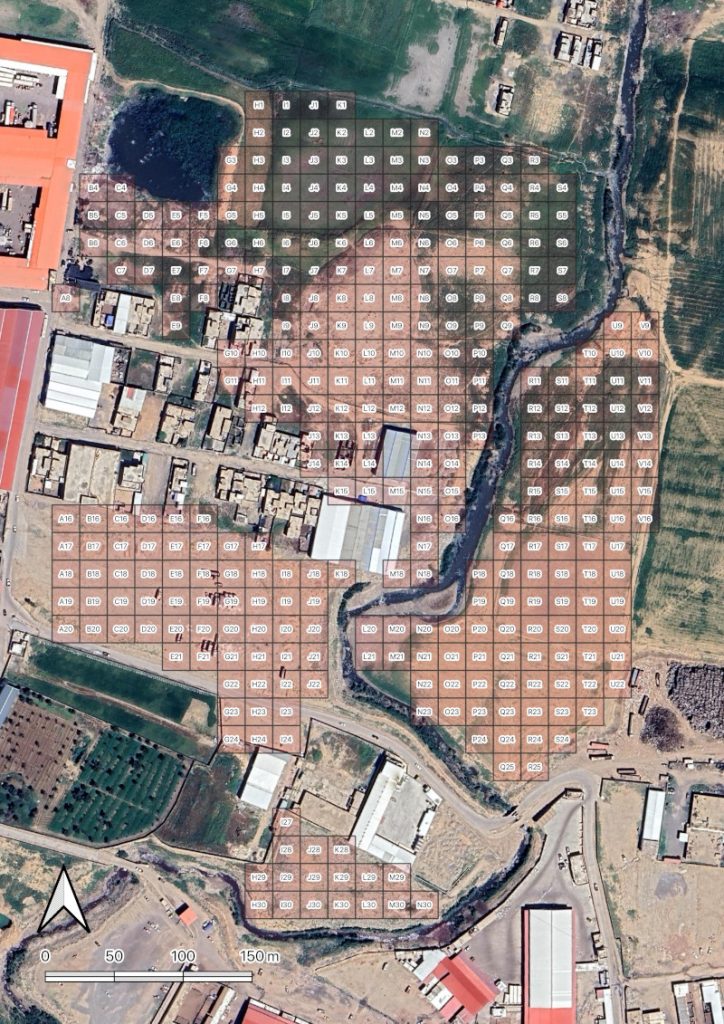

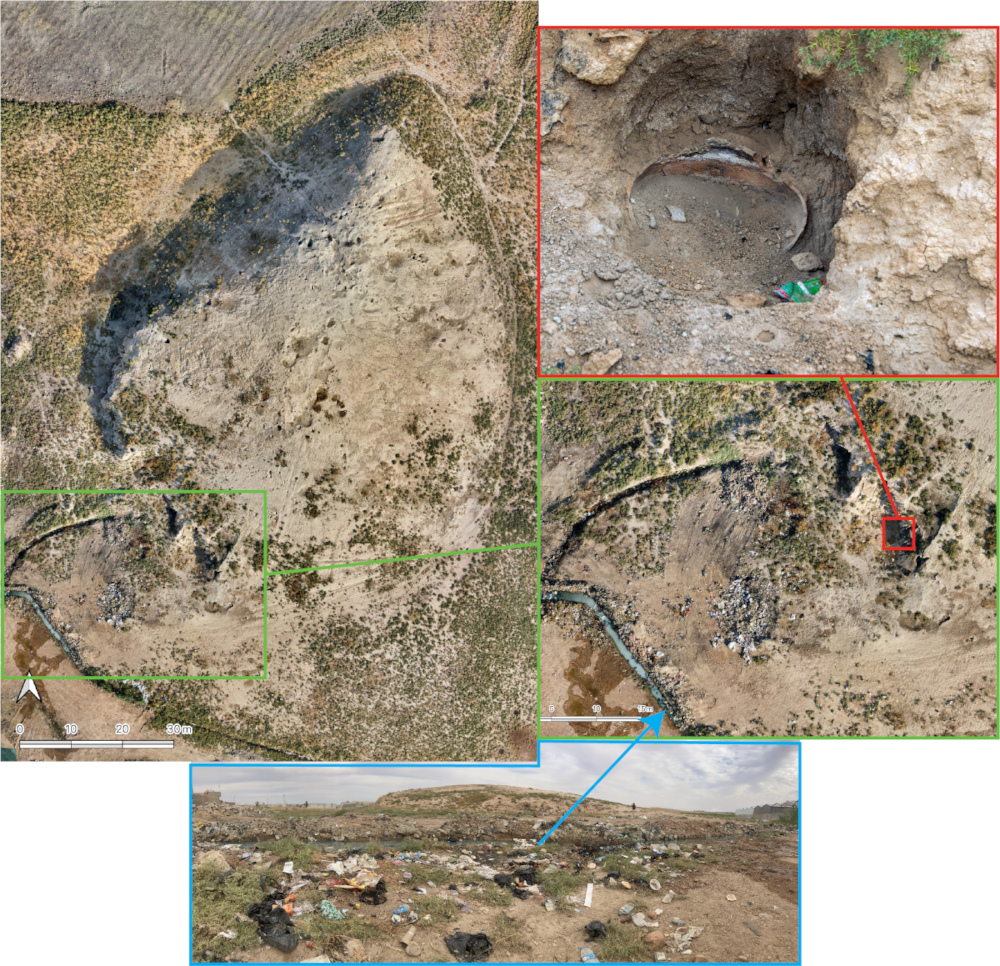

Our methodological approach consisted of combining remote sensing data with field walking in order to obtain a complete picture of the cultural and physical surroundings of the site. Prior to our work in the field, we explored the landscape around the site using satellite imagery (Corona, Hexagon, and Landsat) to document any changes that took place at the site between the late 1960’s and present day. In the field, we carried out a UAV (drone) survey of the site in order to obtain a high-resolution digital elevation model (DEM) and render a 3D model of the site and its surroundings (Fig. 2).

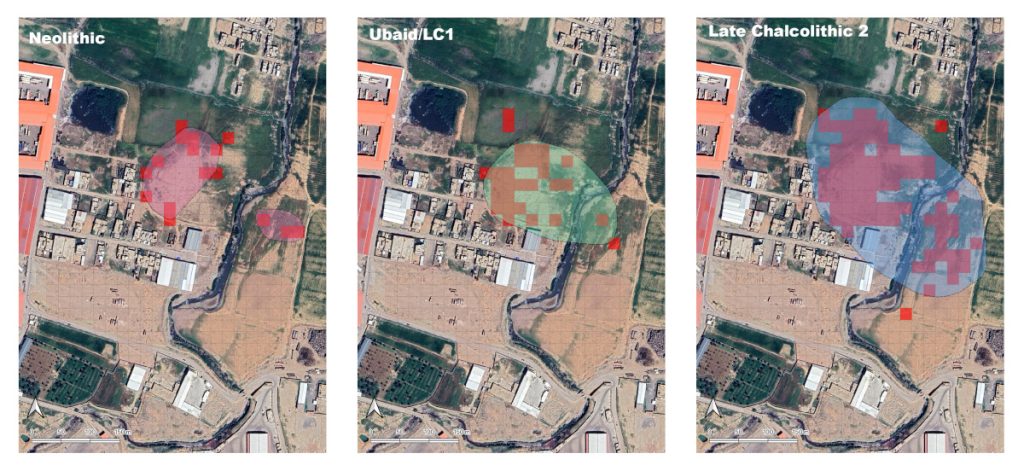

This was an important initial step that aimed to create an accurate plan of the site and to document its present condition, and assess any possible future conservation threats. Our second step was to establish a 20×20 m collection grid around the site as a guide for systematic surface collection that allowed us to explore the distribution of materials from each period as a proxy for settlement extent (Fig. 3).

The survey work had two important aspects to it. First, from the overall scientific questions PUG has been trying to address, Tell ‘Arna produced an occupation sequence that complements that of our other site Tepe Gawra. Whereas the earliest occupation at Tepe Gawra seems to begin from the late Halaf period (5500 BC), occupation at Tell ‘Arna dates back as early as the Neolithic Hassuna period (6200-6000 BC) and continues into the Late Chalcolithic 2 (LC2) period (4200-3900 BC). Similar to what we see at Tepe Gawra (see Abu Jayyab et al. 2024), growth and expansion of Tell ‘Arna takes place during the LC2 where the settlement appears to have doubled in size (Fig. 4). This suggest that nucleation and the formation of aggregated settlements was not unique to Tepe Gawra, but was taking place across the Nineveh Plain, albeit at different scales. Through future excavations we can begin to address the actual scale of aggregation at these sites and how said aggregation may have engendered structural transformations at them.

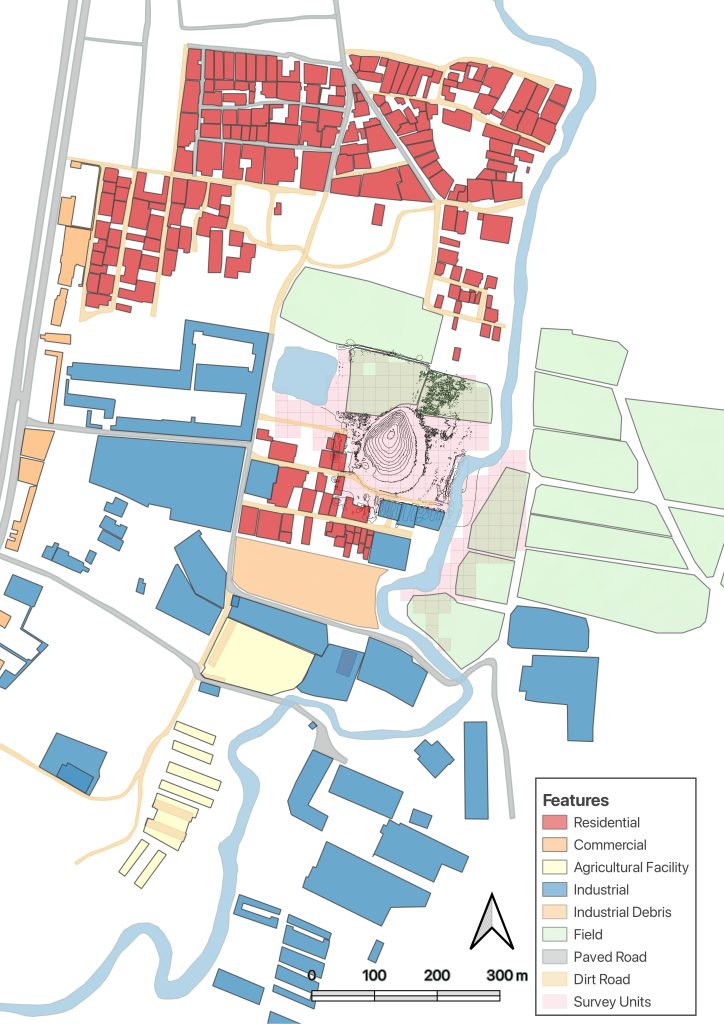

While the mission was primarily meant to be a reconnaissance mission for determining future scientific excavation plans, a second more significant aspect of our documentation has led the PUG team to rethink its priorities. Tell ‘Arna falls in the area of Gogjeli which historically has been an area of open farmland and pasture. With the expansion of the city of Mosul over the past two decades the area here has been slowly engulfed by the city (Fig. 5).

This process has accelerated since with the takeover of the city by ISIS and the subsequent state of disorder and population displacement. Today, as a result, Tell ‘Arna is located in an ever expanding slum where we see the intersection of farmland, factories, and illegal housing encroaching on the site (Fig. 6). Ironically, the project set out to explore the origins of urbanism in the Nineveh Plain and now we can observe rapid urban expansion in real time and its consequences, especially with regards to its impact on cultural heritage.

Slums could be defined as “an overcrowded residential urban area characterized by below standard housing, poor basic services and squalor” (Habitat for Humanity). The conditions around Tell ‘Arna fit that definition as the housing is not part of a zoning plan by the municipality where with the absence of services such as drainage and electricity (electricity is provided through private generators–a common business in Iraq due to the poor infrastructure). While construction of new illegal houses seemed to have stopped, the existing ones are increasingly being choked by industrial buildings and massive storage hangars, with more being built every day (Fig. 7). All these construction activities have been systematically damaging the site, bit by bit. The damage includes bulldozing portions of the site and exposing archaeological remains (Figs. 7-8), cutting a sewage canal through the site (Fig. 8), and increased dumping of household refuse on the site (Fig. 8).

On a more positive note, participation of two University of Toronto students in the work at Tell ‘Arna has opened up new opportunities for them to refine their skills in archaeological survey, material analysis, and leadership. Moreover, we also nurtured deeper collaborations with local stakeholders and members of the local SBAH office in Mosul, through collaboration on field work and opening up conversations with the local community.

Most significantly, work at Tell ‘Arna has shaped our future approach and allowed us to develop a tailored approach to the site in upcoming seasons. While this work started as an exploratory expedition, it has transformed into one that aims to address the threats to the cultural heritage as a point of departure.

Parallel to understanding trajectories towards complexity in the Nineveh Plain, we are developing an approach that preserves the site initially by constructing a fence that prevents the urban push onto the site. Of course, this is not enough as we see that cultural heritage should not alienate the local inhabitants, but on the contrary should, in our opinion, generate a sense of ownership and pride. Accordingly, we see the potential of weaving the site into the fabric of this emergent community of Gogjeli by establishing a park, around the site that includes walkways, educational signs, benches, playground, and a mini-football field to accommodate the local inhabitants of the neighborhood. Through these steps we aim to provide the local inhabitants with a sense of ownership of the space without creating the alienating impact that usually surrounds cultural heritage projects (see Isakhan and Meskell 2019). By converting the area into a usable and functional space for the inhabitants we hope that it would become a place that has value for them and one that they respect and take care of. We also hope it becomes a place that may stimulate their curiosity and one which they can engage with intellectually.

References cited

Abu Jayyab, K. Schwartz, I. Al-Hussainy, A. Batiuk, S. Glasser, A. & Hadi H. 2024 “The Tepe Gawra Lower Town Survey 2022, Iraq.” Bulletin of the American School of Overseas Research, Bulletin of the American Society for Overseas Research, BASOR vol. 392: 55-82.

Habitat for Humanity Urbanisation and the Rise of Slum Housing: https://www.habitatforhumanity.org.uk/blog/2018/09/urbanisation-slum-housing/

Isakhan, B. and Meskell, L. 2019 “UNESCO’s Project to ‘Revive the Spirit of Mosul’: Iraqi and Syrian Opinion on Heritage Reconstruction After the Islamic State.” International Journal of Heritage Studies: 1-16.

Read about applying for a 2025 ASOR Project Grant.

Deadline: February 24

Latest Posts from @ASORResearch

Stay updated with the latest insights, photos, and news by following us on Instagram!

American Society of Overseas Research

The James F. Strange Center

209 Commerce Street

Alexandria, VA 22314

E-mail: info@asor.org

© 2023 ASOR

All rights reserved.

Images licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License

COVID-19 Update: Please consider making payments or gifts on our secure Online Portal. Please e-mail info@asor.org if you have questions or need help.