Table of Contents for Bulletin of ASOR 392 (November 2024)

Pp. 1-20: “Terra-cotta Roof Tiles in the Ancient Synagogues of Judaea/Palaestina,” by Mechael Osband

Terra-cotta roof tiles are some of the most common and volume-intensive finds in the excavation of ancient synagogues, but their significance has received only minor consideration. This article reviews the evidence for terra-cotta roof tiles, which were the preferred roofing used in ancient synagogues in the Late Roman and Byzantine periods. A change took place from non-tiled roofs in Early Roman synagogues to the common use of terra-cotta roof tiles in the later synagogues. It will be suggested that this shift in roofing style was not merely a functional one, but part of the broader developments in synagogue-building, from a place of gathering in the Early Roman period, with an unassuming flat roof, to a more ornate and monumental structure (both internally and externally) with a prominent high tiled roof in plain view.

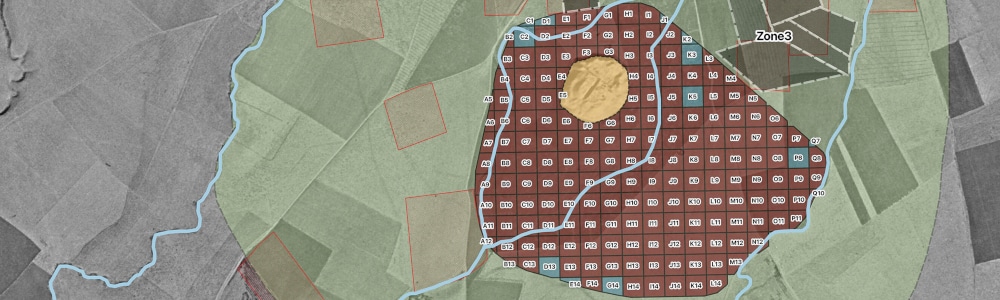

Pp. 21-54: “Reconstructing Late Prehistoric Occupation in the Southern Levant: Irbid as a Case Study for Settlements and Funerary Patterns,” by Antoine Caminada, Tara Steimer-Herbet, Lamia Al-Khoury, and Marie Besse

The region of Irbid (Jordan) in the southern Levant has been known for its megalithic structures since the end of the 19th century. But despite hundreds of dolmens inventoried, it has never been the subject of an in-depth study. This article contributes to a better understanding of human occupation in the area during the 4th and 3rd millennium B.C.E., based on unpublished data collected in September 2005 by a co-directed Jordanian and French mission (University of Yarmouk and the French Institute of the Middle East–Institut français du Proche-Orient Damascus). Data acquisition analysis was realized thanks to a Geographic Information System (GIS) allowing the authors to map and study the spatial relationships between the various elements, with an emphasis on the relationship between the funerary and domestic spheres. By placing the dolmen necropoleis and settlement sites (both double-apsed and rectangular houses) of the north Jordanian Plateau within the general context of the southern Levant, the authors question the “classic” model linking nomadism and megalithism, and bring forward a more sedentary perspective.

Pp. 55-82: “The Tepe Gawra Lower Town Survey 2022,” by Khaled Abu Jayyab, Ira Schwartz, Abbas Al-Hussainy, Stephen Batiuk, Arno Glasser, and Hossam Hadi

Tepe Gawra has long been seen as an essential site for late prehistoric and early historic periods, not only in Iraq but for the entirety of northern Mesopotamia. This importance stems from its long sequence, and its implications for understanding the development of societal complexity. Despite its small size, Tepe Gawra has produced evidence of highly specialized practices that overshadowed farming. This has led to the suggestion that the site was a “center” at the top of an administered network. Some scholars have challenged this assertion and suggested that the site had a lower town, which acted as the source of agriculture goods for the site. Since the area had been closed off to archaeological work this debate has not been resolved. Through recent survey work around Tepe Gawra, the authors show that there was an extensive lower town dating to the Late Chalcolithic and Early Bronze Age stages of occupation. These findings show that Tepe Gawra was a large self-sustaining settlement exploiting its own agricultural hinterland.

Pp. 83-110: “Biography of a Neo-Assyrian Relief Fragment from Nineveh,” by Irene Bald Romano, Kelly Ann Moss, and Gina Watkinson

This article presents the biography of a Neo-Assyrian gypsum relief fragment from Ashurbanipal’s 7th century b.c.e. North Palace at Nineveh, now in the Arizona State Museum, University of Arizona. Its discovery by British explorers in late 1853 or early 1854, its journey to the United States, probably in the mid-19th century through missionaries in Ottoman Mesopotamia, its connection with the circus impresario P. T. Barnum and Tufts College, and its acquisition in 1959 by the Arizona State Museum are discussed, along with the changing uses and meaning of the object in its various contexts. The fragment depicts fat-tailed sheep being led in procession by a royal eunuch. It is related to a larger relief fragment in the British Museum that was positioned to the right of this fragment, allowing some conclusions about its probable location within the North Palace and interpretations concerning its iconography.

Pp. 111-137: “The Parthian Manor House of Sarab-e Murt in the Context of the Iranian Architectural Tradition,” by Yousef Moradi

This article presents the results of archaeological field excavations at the site of Sarab-e Murt, located on the outskirts of the town of Gilan-e Gharb in the Kermanshah province of Iran. The investigations, conducted in 2007 and 2008, brought to light an extraordinary royal residence dating back to the Late Parthian period. The aim of this article is to contextualize the architectural design and layout of the Sarab-e Murt building within the broader landscape of palatial architecture in the Iranian world, with historical roots extending as far back as the Achaemenid period. By examining the development of the plans of palatial houses, we gain valuable insights into the dynamics of change across both time and space. Furthermore, this article seeks to advance hypotheses concerning the origins of Parthian ayvan-style houses plans within the larger context of the Iranian cultural sphere.

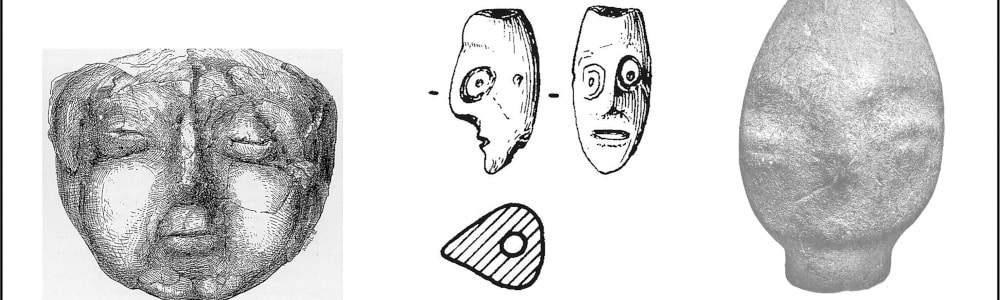

Pp. 139-149: “The Lost Look: A Human Neolithic Figurine from Horbat Sasay (Israel),” by Ianir Milevski and Alla Nagorsky

A human figurine carved on a large limestone cobble was found in the excavations of Horbat Sasay, conducted on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority. It schematically portrays eyes and a mouth and, like other types of human head representations found in the region, it is suggested that it belongs to the southern Levantine Neolithic period. Together with the description of the figurine, comparisons are presented to other known figurines depicting the human face from the Levant and other nearby regions, as well as an interpretation of these human faces and their expressions in relation to the drastic changes that occurred in these regions during the so-called Neolithic revolution and the social organization of the late prehistoric communities of the Levant.

Pp. 151-177: “Defending the Vedi River Valley of Armenia: The Fortification and Refortification of a Flatland-Mountain Interface,” by Peter J. Cobb, Elvan Cobb, Hayk Azizbekyan, Artur Petrosyan, and Boris Gasparyan

The mountainous topography of the Armenian Highlands and the South Caucasus accentuates the importance of valleys as areas of habitation and as conduits among these interspersed settlement areas. The Vedi River Valley of Armenia, located along the southeastern edge of the Ararat Plateau (Plain), serves as one such important transportation route in and through these highland areas. At the center of the mouth of this valley sits the prominent Vedi Fortress, ideally situated for defense of this route and landscape. The site was first fortified during the Late Bronze Age, perhaps during the centralization of power by a local polity contained within the valley. Burned down and abandoned at the end of the Iron Age I, the fortress would then see varied reuse through several later periods given its prominent location and proximity to other local power centers. Of particular importance is its refortification during the Early Medieval (Late Antique) period, when Armenia was under Sasanian Persian suzerainty. This article presents the results of archaeological fieldwork in this valley and at the fortress, followed by a discussion of the landscape’s fortification and refortification during these two periods. The Vedi River Valley provides a case study for examining control, mobility, and the negotiation of local and remote power within the specific contained landscape of a river valley in mountainous terrain.

ASOR Members with online access: log into ASOR’s Online Portal here. Once logged in, click the JOURNALS tab in the top navigation bar. Tutorials for how to log in to the Online Portal as well as how to navigate to the Portal Journals page can be found here.

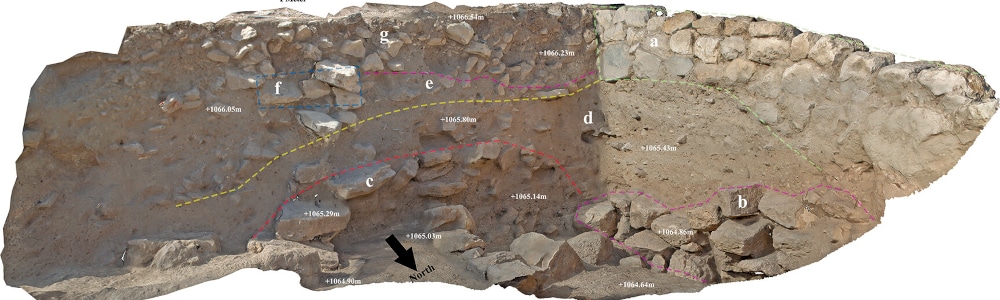

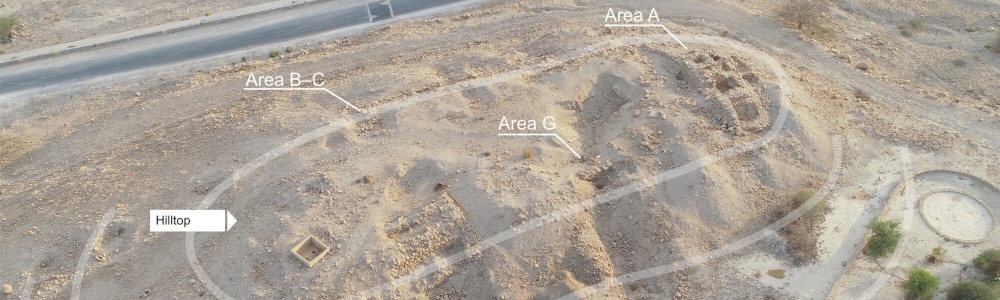

Pp. 179-205: “Revisiting Late Iron Age En-Gedi: A Stratigraphic Reassessment of Stratum V at Tel Goren,” by Avraham Mashiach and Uri Davidovich

The oasis of En-Gedi, on the western shore of the Dead Sea, served during the late Iron Age as a regional hub for the Judahite activity in the Judean Desert. The main Iron Age site in En-Gedi is Tel Goren, a small mound in the oasis plain, excavated in the 1960s by Benjamin Mazar and Immanuel Dunayevsky. The exposed Iron Age remains, attributed to the lowermost occupation (Stratum V), yielded substantial material assemblages associated with a thick destruction layer dated to the early 6th century b.c.e. The excavators interpreted the site as an unfortified, short-lived agricultural estate dedicated to the production of high-valued commodities. Drawing on a critical reassessment of past excavations, coupled with new evidence gathered in small-scale excavations conducted in 2020, it is suggested that the development of late Iron Age Tel Goren was a gradual process that involved at least two major phases, as well as the construction of a fortified compound on the summit of the hill. The implications of this suggestion are further examined within the broader regional and historical context, shedding new light on the multiphase trajectory of Judah’s expansion into its eastern fringe during the late monarchic period.

ASOR Members with online access: log into ASOR’s Online Portal here. Once logged in, click the JOURNALS tab in the top navigation bar. Tutorials for how to log in to the Online Portal as well as how to navigate to the Portal Journals page can be found here.

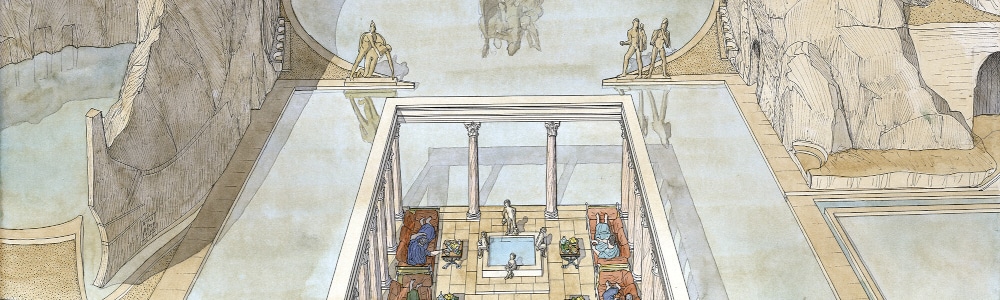

Pp. 207-237: “Dine and Worship: The Roman Complex in Front of the Pan Grotto in Paneas/Caesarea Philippi,” by Adi Erlich and Ron Lavi

Paneas, situated at the foot of mount Hermon, is where the Hermon River emerges from a spring at the foot of a cliff with a natural cave. In the Hellenistic and Roman periods, the cave and nearby terrace served mainly for the cult of Pan. Herod the Great built in Paneas a temple to Augustus, and his son erected there his capital, Caesarea Philippi. A salvage excavation was recently conducted in front of the cave in the area that formerly was identified as Herod’s Augusteum. The new excavations have proven that during the Roman period, the place was unroofed and open to the cave, which was full of water. The water flowed out through a large aqueduct, water installations were constructed in the courtyard, and niches flanked on the west and east. The complex is dated to the last third of the 1st century c.e. and is attributed to Agrippa II, who built there a nymphaeum-triclinium facing a grotto in Italian style. Afterward, the courtyard was used as a cult place to Pan, and hydromantic rituals were performed in the cave. The sources for this complex will be discussed, as well as the changes that took place there through time.

ASOR Members with online access: log into ASOR’s Online Portal here. Once logged in, click the JOURNALS tab in the top navigation bar. Tutorials for how to log in to the Online Portal as well as how to navigate to the Portal Journals page can be found here.