Table of Contents for Near Eastern Archaeology 85.2 (June 2022)

Pp. 84–89: “Tel Reḥov: The Site and Its Excavation,” by Amihai Mazar

The author offers a brief introduction to the excavations at Tel Reḥov, beginning with a description of the mound. This is followed by a summary of the appearance of the toponym Reḥob in written sources; the identification of the site; and a brief survey of the excavation project, including its goals, the core staff, the excavation areas and the methods used. Finally, it presents the stratigraphic sequence and the structure of the final report that appeared in 2020, as well as reference to an exhibition held on the excavations.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 90–95: “Tectonic Activity and Site-Formation Processes at Tel Reḥov,” by Uri Davidovich and Ezra Zilberman

The site of Tel Reḥov is located on one of the most active tectonic fault zones in the Near East—the Western Marginal Fault of the Dead Sea Rift—and was prone to tectonic movements, which had a significant effect on site-formation processes. Geoseismic and geoarchaeological studies conducted as part of the Tel Reḥov excavation project suggest that the site was located on an uplifted tectonic block (horst) bounded by faults on the north, west, and south. Recurrent tectonic activity during the Late Holocene resulted in an eastward-tilting of layers and the entire mound, contributed to the shaping of mound boundaries, and constrained the extent of postdepositional erosion.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 96–109: “The Canaanite City at Tel Reḥov: From the Early Bronze Age to the End of the Iron Age I,” by Amihai Mazar, Uri Davidovich, Nava Panitz-Cohen, Yael Rotem, and Amir Sumaka’i Fink

The article describes the development of the city throughout the Late Bronze–Iron Age I sequence. A massive Early Bronze fortification system was revealed on the slope of the upper mound. Following the end of EB III, there was an occupation gap until LB I/IIA, when a ten hectare Canaanite city was founded and became one of the largest cities in the southern Levant, identified with Reḥob, mentioned in several Late Bronze Age sources. The unusual foundation of a city in the Late Bronze Age may have been related to the Egyptian garrison town at nearby Beth-Shean. Though exposure was limited in scope, the results indicate that unlike many other sites, Reḥov maintained its Canaanite urban character throughout this period with no occupation gap.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 110–125: “Tel Reḥov in the Tenth and Ninth Centuries BCE,” by Amihai Mazar

Tel Reḥov was the location of one of the largest Iron Age cities in northern Israel during the Iron Age IIA, the main period investigated at the site. This article summarizes the stratigraphy, main architectural features, aspects of daily life and material culture, industries, trade relations, writing, religion and iconography, as well as chronology and historical questions. The finds reflect cultural and economic processes that the city and its environs underwent during this momentous time. Canaanite traditions alongside innovations, economic prosperity, vibrant trade relations with the Phoenician coast and, indirectly, with Egypt, Cyprus, and Greece are evidenced. Notable is the exceptional and peaceful continuity between the Iron I and Iron II cities. The city may have been the hometown of the Nimshi clan, to which Jehu belonged. The city suffered a violent destruction, probably at the hands of Hazael, king of Aram-Damascus.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 126–131: “The Apiary at Tel Reḥov: An Update,” by Amihai Mazar, Nava Panitz-Cohen, and Guy Bloch

The apiary discovered in Stratum V at Tel Reḥov in 2005–2007 remains unique in the archaeology of the ancient Near East. Here the authors briefly summarize the data previously published in this journal and add results of new studies, mainly concerning the identification of ancient charred bees trapped in burnt honeycombs found in the hives. Measurements of two wings and one leg, and statistical work based on existing database of modern subspecies, are inconsistent with the Syrian subspecies local to Israel (Apis meliferra syriaca), but were found to be similar to the Anatolian bee (Apis meliferra anatoliaca). We discuss the implications of this result, suggesting trade relations with southern Anatolia. The authors suggest that the beeswax was perhaps related to the copper-based metallurgical industry that entailed casting in the lost wax method, at a time when the copper trade based on the Arabah mines was at its peak.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 132–145: “The Exceptional Ninth-Century BCE Northwestern Quarter at Tel Reḥov,” by Nava Panitz-Cohen and Amihai Mazar

An exceptional architectural complex at Tel Reḥov dating to the last phase of the Iron IIA occupation in the ninth century BCE (Stratum IV) was uncovered in Area C, located on the northwestern and highest part of the lower mound. Each of the buildings belonging to this quarter, built exclusively of mud brick, had an exceptional architectural layout, while at the same time, they were interrelated and organized according to a preplanned agenda. All the buildings were completely destroyed by the severe fire that resulted in the abandonment of the lower city at the end of Stratum IV. The abundance of rich remains found in the destruction debris just below topsoil, many of them of a unique nature and reflecting quotidian, cultic, and industrial activities, as well as three inscriptions with personal names, indicate the special role played by this complex, particularly the largest and most exceptional: Building CP.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 146–151: “Facing Assyria: Tel Reḥov in the Late Ninth and the Eighth Centuries BCE,” by Amihai Mazar and Robert A. Mullins

Following the violent destruction of Stratum IV the city at Tel Reḥov was rebuilt, yet limited to the upper mound, an area of about three hectares. Two main strata can be attributed to the Iron IIB. A fortification system found in Area B had an earlier phase consisting of a casemate wall with a tower and a later phase with a wide city wall. Dwellings and courtyards were excavated in Areas A, B, and J. The Assyrian destruction was severe, evidenced by the slaughter of people in their homes in Area A. Scanty squatter activity was discovered following the destruction, as were seven burials, some with Assyrian-type pottery bottles, perhaps evidence of Assyrian presence on the summit. One of the burials is especially rich in finds and perhaps belonged to a high-ranking person. (Please note: This article contains images of human skeletal remains.)

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 152–158: “The Iron Age II Figurines and Zoomorphic Vessels of Tel Reḥov,” by Raz Kletter and Katri Saarelainen

Forty-nine Iron Age II anthropomorphic and zoomorphic clay figurines and vessels were found at Tel Reḥov. Clay was an inexpensive material and small figurines were a common item; yet, this small assemblage still holds surprises. All the figurines were published in Saarelainen and Kletter. Here we present a selection of the figurines in order to illustrate their variety and aesthetic appeal, and also to demonstrate the difficulties in studying and interpreting them. What do we see in them? Images of powerful, but nearly forgotten deities? The faces of bygone generations (and of their animals too)? Or, perhaps, portrayals of important priestesses and warriors?

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 159–163: “Metalworking at Tel Reḥov,” by Naama Yahalom-Mack

The excavations at Tel Reḥov yielded hundreds of metal objects and numerous metallurgical remains that attest to on-site metalworking. The study of such remains and their distribution sheds light on metalworking practices at the site, indicating a considerable change between the Late Bronze Age and the Iron Age, which comprised both the choice of raw materials (bronze vs. iron), their origin, and metalworking traditions. Particularly significant is the evidence for an Egyptian metalworking tradition during the Late Bronze Age, indicating that the metal industry at Reḥov may have been tightly controlled by the neighboring Egyptian stronghold at Beth-Shean. Iron Age I metallurgical remains suggest that the smiths reverted to Canaanite metalworking practices after the Egyptians’ departure. Iron was introduced into common use during the Iron Age IIA, the tenth and ninth centuries BCE.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 164–169: “Animal Remains from Tel Reḥov: Economy and Culture in the Iron Age Settlement,” by Nimrod Marom, Karin Tamar, and Sierra Harding

The Iron Age settlement at Tel Reḥov has yielded a large and well-preserved faunal assemblage. Zooarchaeological analysis of these animal remains from the Iron Age is used to discuss aspects of settlement economy, examining both development through time and similarity with contemporaneous assemblages. The results show that the animal economy at the site was not very different from contemporary valley sites in the Southern Levant, but suggest a certain development of the pastoral economy between the Iron Age I and II. In addition, some insights pertaining to the symbolic use of animals can be gleaned from the faunal remains, specifically in respect to side preferences.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

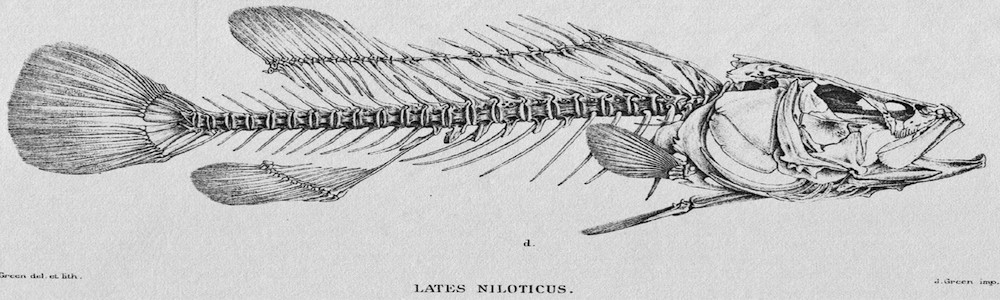

Pp. 170–171: “Fish Imported from a Distance and Consumed at Tel Reḥov,” by Omri Lernau

Excavations at Tel Reḥov brought to light an assemblage of fish remains, dated to different periods covering almost the entire era of occupation of the site. Most kinds of fish were probably purchased in markets along the Mediterranean coast, including local marine and freshwater fish and also several kinds of fish imported from the Nile and from the hypersaline lagoon of Bardawil. Few fish were imported to Reḥov from the Red Sea. The long-lasting supply of many kinds of fish to Reḥov, together with similar findings in the adjacent Tel Beth-Shean, suggest an organized enterprise of commerce between the Mediterranean coast and the Jordan Valley.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.