You can receive NEA (and other ASOR publications) through an ASOR Membership. Please e-mail the Membership office if you have any questions.

Pp. 100–109: “Yotvata in the Southern Negev and Its Association with Copper Mining and Trade in the Early Iron Age,” by Lily Singer-Avitz

Yotvata is the modern name of a small oasis located on the western edge of the southern Arabah Valley in the southern Negev. In Arabic it was called ‘Ein Ghadian, probably after the Saxaul bush (Haloxylon persicum) (ghada in Arabic), commonly found in the surrounding sands. The Arabah Valley stretches from the southern edge of the Dead Sea to the Gulf of Eilat (Aqaba). The valley has an extremely hot and dry climate. Absolute temperatures in the summer reach 45° C and the mean annual rainfall is 30 mm (Bruins 2006: 29–32). The oasis is situated on the main road to Eilat, about 40 km (25 mi.) north of the city, at an elevation of 125 m above sea level.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 110–119: “Everything But The Oink: On the Discovery of an Articulated Pig in Iron Age Jerusalem and Its Meaning to Judahite Consumption Practices,” by Lidar Sapir-Hen, Joe Uziel, and Ortal Chalaf

Pork consumption and avoidance during the Iron Age in the southern Levant is extensively discussed in the context of the identity of the populations of ancient Israel. It is often examined by calculating pig frequencies in faunal assemblages (Hesse 1990;Hesse and Wapnish 1997, 1998; Faust and Lev-Tov 2011; Maeir, Hitchcock, and Horwitz 2013; Meiri et al. 2013; Sapir-Hen et al. 2013; Faust and Lev-Tov 2014; Sapir-Hen, Meiri, and Finkelstein 2015; Maeir and Hitchcock 2017; Sapir-Hen 2019a). Recent studies that reviewed data on pig frequencies in correlation to the subphases of the Iron Age have shown that while frequencies of pork consumption fluctuated in the Northern Kingdom, it remained constantly low in Judah throughout the Iron Age (Sapir-Hen et al. 2013; Sapir-Hen 2019a). In Jerusalem, the capital of Judah, low frequencies or absence of pigs (0–2 percent of livestock) were found in all excavated sites (see further below). Thus, the discovery of an articulated pig in an Iron Age IIB (eighth century BCE) building during recent excavations along the eastern slopes of the City of David is intriguing.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

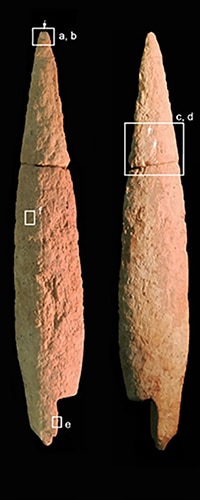

Pp. 120–129: “A Bone Projectile Point and Its Possibly Associated Workshop from the Iron Age IIA of Tell eṣ-Ṣafi/Gath,” by Liora Kolska Horwitz, Maria Eniukhina, Ron Kehati, Iris Groman-Yaroslavski, and Aren M. Maeir

Although not as old as artifacts made of stone, the manufacture and use of bone tools is of great antiquity, with the earliest known bone artifacts from Lower Paleolithic sites in Africa: Olduvai Gorge (Tanzania) dating to 2.1–1.1 Ma and the sites of Swartkrans, Sterkfontein, Drimolen (South Africa), dated to around 1.8/1.7 Ma to 1.4/1.0 Ma (Bradfield and Choyke 2016). From this point on in time, alongside stone and metal artifacts, universally, people continued to manufacture and use bone tools. This practice continued even into recent times, as attested by innumerable ethnographic examples of bone artifacts and ornaments (e.g., Stordeur 1980; Ayalon and Sorek 1999; Walshe 2008; Legrand-Pineau et al. 2010; Stone 2011; Bradfield 2012). Often, lithic and metal tools were used for bone working, illustrating the continued value of bone even in historic periods.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 130–139: “Divine Cults in the Sacred Precinct of Girsu,” by Sébastien Rey

Sumer in present-day southern Iraq is the heartland of the first cities and birthplace of writing (fig. 1). It is where, between 3500 and 2000 BCE, its inhabitants, the Sumerians, instituted the first codes of law, advanced metallurgy to craft new tools and weapons; enhanced wheel technology and invented the potter’s wheel. The Sumerians organized long-distance trade over land and sea; they carved monumental sculptures and wrote poems, epic myths, and musical hymns (Jacobsen 1987; Bottéro and Kramer 1989). They created irrigation canal networks and built bridges, temples, and stepped towers “reaching the heavens,” their time-honored ziggurats (George 1993). It is the sum of these innovations that characterizes Sumer as one of the first civilizations of the ancient world.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 140–147: “The Spiritual Life of Teleilat Ghassul and Building 78,” by Ben Greet

Teleilat Ghassul is a 20 ha Chalcolithic site, likely dating to between 4500–4250 BCE (Gilead 2011: 14), that consists of many interconnected domestic buildings interspersed with rooms containing elaborate frescoes. The discovery of infant burials, ritual objects, and frescoes points toward an elaborate spiritual life of the community that inhabited the site. The aim of this paper is to explore an aspect of that spiritual life in detail through a reexamination of the frescoes of Building 78 on Tell 3. Building 78 provides an excellent opportunity for this type of study, as its context links it with Drabsch’s (2015a: 52) model of lineage houses and their centrality to the spiritual life of Ghassul. Through a reinterpretation of the bird fresco and spook masks focused on their connection to the ecology of the region, I hope to demonstrate that these frescoes were thematically linked through concepts of spiritual liminality and annual cycles. This thematic link can then be used to posit the types of rituals that may have been performed by the Ghassulian community within Building 78.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

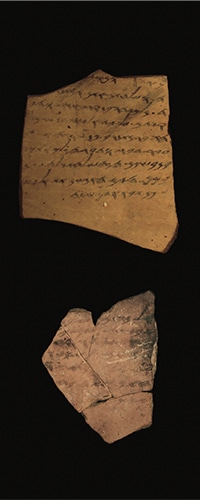

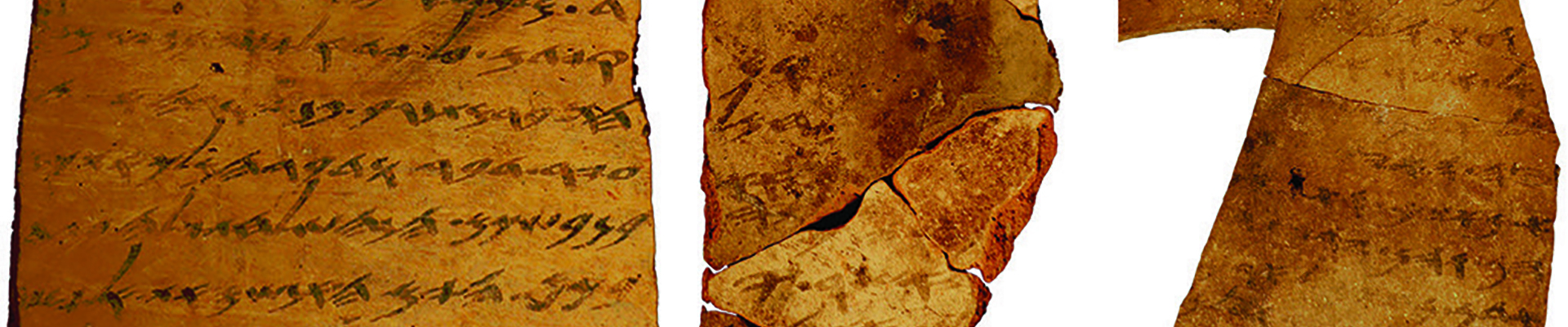

Pp. 148–158: “Literacy in Judah and Israel: Algorithmic and Forensic Examination of the Arad and Samaria Ostraca,” by Shira Faigenbaum-Golovin, Arie Shaus, Barak Sober, Yana Gerber, Eli Turkel, Eli Piasetzky, and Israel Finkelstein

A highly discussed issue in the fields of Hebrew epigraphy and biblical research is the level of literacy in the Iron Age kingdoms of Israel and Judah (Rollston 2010; Davies and Römer 2013; Schmidt 2015). Treating this topic using biblical texts, for example, the references to scribes at the time of a given monarch, may lead to circular argumentation: The reality behind a given account may reflect the time of the authors, who could have lived centuries later and retrojected their own situation back onto earlier history. A preferable methodology is to consider the material evidence—the corpora of Iron Age Hebrew ostraca from archaeological excavations. The idea is to use algorithmic and forensic methods to distinguish between handwritings and thus the number of authors in a given corpus.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 159–165: “Communal Architecture at Boncuklu Tarla, Mardin Province, Turkey,” by Ergül Kodaş

Villages of the Preceramic Neolithic in the Near East are marked by a new style of construction, created to play a new, essential function. Indeed, it is in this period that, outside of residential habitations, communal buildings make their first appearance in the heart of Near Eastern villages. It is without doubt one of the first clear, historical attestations of social differentiation/organization in architecture. Truly, reflections on such constructions lead one to attribute to them adjectives aimed at encapsulating their supposed functions, such as “collective,” “communal,” “monumental,” “public,” “cultic,” “storage structures,” or even “megalithic” (Aurenche and Kozlowski 2000; Stordeur 2014; Watkins 2006; Goring-Morris and Belfer-Cohen 2014; Hauptmann 2012). The terminology here reflects considerably varying interpretations, often complementary and essentially derived from the architectural data, as the buildings reveal ground plans and internal structures that are quite distinct.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.