You can receive NEA (and other ASOR publications) through an ASOR Membership. Please e-mail the Membership office if you have any questions.

Pp. 4–11: “Archaeogaming: When Archaeology and Video Games Come Together,” by Tine Rassalle

The connection between archaeology and video games might come as a surprise to some, especially to those who have never played a video game. However, games and “playing” as a field for serious scholarship and historical research have been explored since the 1930s, when Dutch cultural historian Johan Huizinga wrote that “play is older than culture.” In Homo Ludens, Huizinga makes the case that from human play comes the creation of cultures, the forming of meaning, and the learning and transmitting of knowledge. His “playing man” engages in game-like practices and rituals, in politics, and in war and violence, showing that play and culture exist side by side as a “twin-union,” but play came first (Huizinga).

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 12–21: “Beyond Tomb and Relic: Anthropological and Pedagogical Approaches to Archaeogaming,” by Matthew Winter

The advent of the computer chip has radically altered human life at a global scale, and with increasing access to digital platforms it was inevitable that digitization would reshape popular culture. The video game industry is one of the fastest growing sectors in technological and entertainment industries, reaching an enormous audience. It is now estimated that some 2.5 billion people play games worldwide, with 211 million American adults, 52 percent of whom are college educated (see Rassalle in this issue) ().Figure 1. Infographic of gamer demographics. From Entertainment Software Association. Source: https://www.theesa.com/esa-research/2019-essential-facts-about-the-computer-and-video-game-industry/.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 22–31: “Formless and Void: The Emergence of Biblical Lands in Early Religious Video Games (1982–1991),” by V. Gonzalez and Tine Rassalle

This essay examines how digital signifiers across the first decade of religious video games (1982–1991) helped players to situate themselves in the biblical landscapes. Spanning eight gaming platforms, and many different genres, from puzzle games to adventure, 17 games depicting biblical lands were created in this time period, offering us a fresh perspective on the question of how the past is presented through video games.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 32–43: “Might, Culture, and Archaeology in Sid Meier’s Civilization,” by Shannon Martino

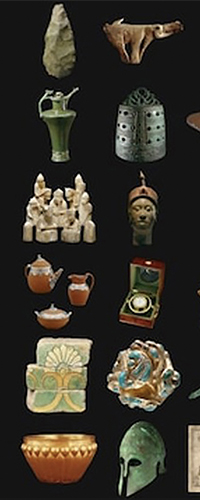

That video games should be socially conscious, engaged with political discourse, or historically accurate may not immediately come to mind: Video games are entertainment. One popular game series, Sid Meier’s Civilization (Civ), however, has run into multiple issues regarding its representations of culture(s) and history, particularly of underrepresented societies. This is unsurprising given the premise of the game, where users create civilizations based upon predefined, somewhat historically informed, often unfamiliar historical cultures. Players are encouraged to learn about these from the quasi-academic, imbedded encyclopedia Civilopedia, from in-game historical allusions and scenarios, game units, buildings, and archaeology.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 44–51: “Persia’s Victory: The Mechanics of Orientalism in Sid Meier’s Civilization,” by Angus Mol and Aris Politopoulos

A large Persian army consisting of archers, siege equipment, and fearless Immortals is wedged in a narrow strip between the sea and the mountains. Beyond this pass lies the Greek heartland and the ancient cities of Corinth and Athens. All that stands between Persia and their conquest of Greek cities is a handful of charioteers and bowmen. The battle commences. Arrows cloud the sky but fail to stop the advance of the Immortals. The Greek charioteers, caught by surprise and without enough room to maneuver, are quickly defeated. Corinth cannot stand the siege and soon falls. With minimal losses to the Persian army and little time for the Greeks to regroup, the city of Athens is soon to follow. In a defeat without distinction, the capital of the Greek world is ceded to the Persians. A few years later, nothing but toponyms are left to remind one of the once thriving Greek civilization.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 52–61: “Virtual Ziggurats: Orientalist Views and Playful Spaces,” by Aris Politopoulos

With this quotation, this fifth-century BCE Greek historian provides us with a vivid description of Etemenanki, the ziggurat of Babylon. The ziggurat is one of the most enduring symbols of the ancient Near East: From paintings to movies to books to video games, versions of the stepped constructions emerge in popular culture and imagination all the way from classical Greece until today. One could even argue that the ziggurat is a transhistorical symbol (Crowther ); it has existed as a symbol not only produced by and related to the ancient Near East, but has transcended its original historical context and has acquired new meanings and images over time. In this article, I explore this transhistoricity of the ziggurat by examining it within western, modern, popular imagination, and particularly within the context of video games. For this, I take an art-historical approach, examining ziggurats from various games to create a ziggurat typology as portrayed in video games. In doing that, I explore how modern conceptions of the ziggurat affect and shape our understanding of the Near East, and how this can be tied to Edward Said’s concept of orientalism (see also Mol and Politopoulos in this issue). I conclude with a brief discussion on how we can reframe the ziggurat within popular culture in order to increase knowledge and awareness about the history and cultures of the ancient Near East today.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 62–70: “Building Kunulua Block by Block: Exploring Archaeology through Minecraft,” by Dominique Langis-Barsetti

The Computational Research on the Ancient Near East (CRANE) Project, directed by Tim Harrison of the University of Toronto, has united scholars from a variety of disciplines across several institutions around the globe since 2012. Originally focused on the Orontes Watershed of southern Turkey and northwestern Syria, the goal of the project is to provide researchers with a collaborative framework in which to leverage the full array of data produced by archaeology in order to shed light on the rise and development of complex societies in the region. The pooled resources and skills of collaborators have allowed the project to visualize and model connections between social, economic, and environmental factors across a range of temporal and regional scales (https://crane.utoronto.ca/).

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 71–78: “Assassin’s Creed Origins: Video Games as Time Machines,” by Christian Casey

Ancient Egypt is far away. Very far away. For too many scholars who study Egypt professionally, it is far away in space. For all of us, it is far away in time—around two thousand years at the nearest point. This distance has consequences. We tend to view the world of ancient Egypt as we would a city on a mountain top: We observe the buildings as amorphous shapes, the people as bug-like creatures moving about at random, the events that shape their lives as momentary flurries of activity. Deliberate study provides an alternative view. Through the telescopic lens of scholarship, individual moments come into focus, are magnified, and become real, but the whole remains an incomplete sum of its disconnected parts. To use a more-familiar metaphor, we modern scholars see either the texture of the bark or the blue-gray smudge of a distant forest (). We have no choice but to miss the forest for the trees, we can never experience them together.Figure 1. Bayek and trusty pet lion in an idyllic Egyptian forest. The only proper way to experience a forest is to walk through one. Screenshot by the author.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 79–85: “Assassin’s Creed Origins Discovery Tour: A Behind the Scenes Experience,” by Perrine Poiron

Assassin’s Creed: Origins was released at the British Museum in September 2017. For this particular event, which was celebrating the tenth anniversary of the Assassin’s Creed franchise, Ubisoft organized a colossal event, inviting influencers from all around the world plus media and some academics. This large event clearly shows the importance of this video game franchise, which started in 2007 with the launch of the first Assassin’s Creed game, set in Crusader Israel. Since then, twelve games have been released, each taking place in a specific time period, from the Peloponnesian War to the Renaissance era to the Victorian period ().Figure 1. All Assassins-Assassin’s Creed Brand. © 2020 Ubisoft Entertainment. All Rights Reserved.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

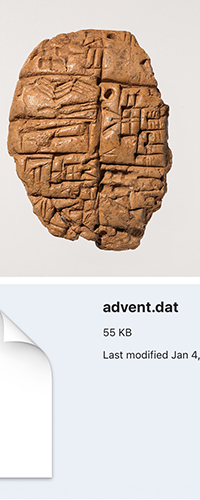

Pp. 86–92: “Colossal Cave Archaeology: Epigraphy, FORTRAN Code-Artifacts, and the Ur-Game,” by Andrew Reinhard

As explained by Tine Rassalle in her article introducing this special issue, video games and archaeology intersect in many ways, all of which can be applied to the archaeology of the Near East. Other authors in this issue describe video games (and their underlying engines) as pedagogical tools, tools for digital visualizations and reconstructions, and offer windows into how archaeology and archaeologists are perceived by both designers and players, which can also inform them about different interpretations of the ancient Near East and its many cultures. In this article, however, I take a different approach, showing that one can take methods, tools, and theories used by more traditional archaeologists working on Near Eastern topics and apply them to work on digital artifacts from the late twentieth century (Reinhard : 49–130).

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.