Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

August 2024

Vol. 12, No. 8

Phoenician Trade Associations in Ancient Greece

By Denise Demetriou

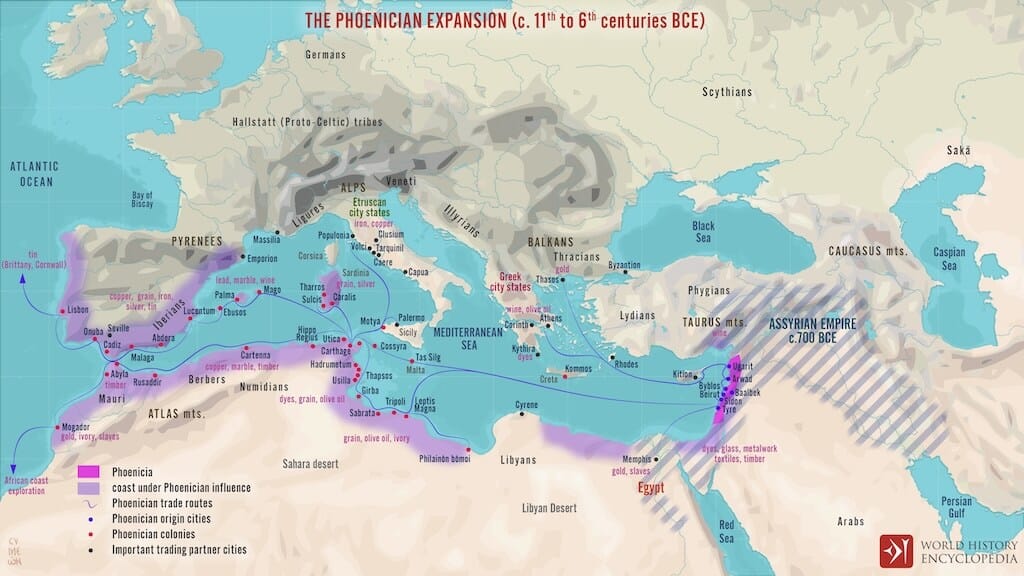

The Phoenicians — famed seafarers, traders, and master craftsmen of the ancient Mediterranean — crisscrossed the sea connecting a vast geographic area from Assyria to Iberia with an extensive network of settlements and trading posts. In the early 1st millennium BCE, they migrated from their homelands of Tyre, Sidon, Byblos, and Arados on the Levantine coast and established several urban centers on Cyprus, Sicily, Sardinia, Malta, the coast of North Africa, Iberia, and the Balearic Islands, and settled as immigrants in Egypt and in Greek polities.

Map of the Phoenician World, 11th cent – 6th cent BCE. By Simeon Netchev, CC BY-NC.

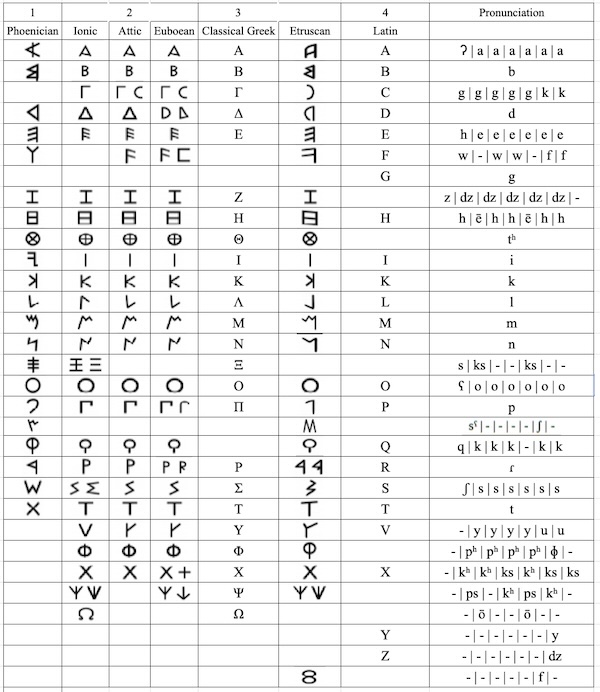

With their maritime ventures and their migratory patterns, the Phoenicians transformed the ancient Mediterranean basin and the societies that they encountered. They created the most important pan-Mediterranean artistic movement of the 8th–6th centuries BCE, conventionally called “orientalizing art;” they reintroduced a writing system adopted by the Greeks, Etruscans, Iberians, and later the Romans, among others; they transferred gods and myths to other groups living in the region; and they established new institutions.

Formation of the alphabet: Phoenician compared with Epigraphic Greek (Ionic, Attic, Euboean versions), Classical Greek, Etruscan, and Latin. Adapted from a chart by Joan Gené, CC BY-SA 4.0.

Ivory box and lid with sphinx handle, in “orientalizing” style. From the Sorbo Necropolis in Cerveteri (Etruria) the object is believed to have been inspired by Phoenician luxury goods and is an example of the wide reach of Phoenician trade and culture. Ca. 650–625 BCE. Walters Art Museum 71.489. Photo courtesy of the Walters Art Museum, CC0.

One of these novel institutions was the phenomenon of professional associations structured around an occupation, the home state of its members, and that state’s patron deity. They first appeared in Athens in the 4th century BCE and were later found on 2nd century BCE Delos and even in 2nd century CE Puteoli in Southern Italy. In prosperous such commercial centers, inhabited and frequented by individuals of different ethnicities who collaborated in trading ventures, these institutions developed to facilitate cross-cultural trade. Indeed, all Phoenician associations recorded in ancient sources were associations of professions related to trade: traders, shippers, and warehouse workers. Such associations were a Phoenician invention of the 4th century BCE that emerged in migrant communities in Athens to represent their interests and provide them a social and physical space for maintaining religious and other cultural ties to their home state.

Although the intricacies of how such associations functioned have largely been lost, surviving inscriptions indicate that the professional associations established by collectives of Phoenician traders in Athens and Delos helped immigrants navigate the legal and other restrictions imposed on them by their host states. These restrictions were significant: without the ability to own land, immigrants could not build their own temples or bury their dead in public cemeteries; without the right to participate directly in government, they had little political say in their communities. Like today’s special-interest groups and nongovernmental organizations, by organizing into collectives, groups of foreigners were able to pool their resources and gain access to avenues through which they could petition their host state, lobby for awards and privileges for their members, and negotiate various rights for the association itself.

A chief way in which these professional organizations served the interests of their members was petitioning the host state for honors and rights not generally available to foreigners or non-citizens. For example, around 360 BCE, Athens granted special privileges in the form of tax exemptions to a group of Sidonian traders resident in Athens. Members of the association were no longer required to pay resident alien taxes, capital taxes, or be liable to finance a chorus for dramatic contests. In the 320s BCE, an association of traders and shippers approached the Athenian state and nominated a Sidonian man named Apollonides for several rewards because of the goodwill he had shown to Athens. Usually, worthy foreigners were sponsored by individual Athenians but the text honoring Apollonides suggests that by forming associations immigrants were allowed to petition the state for awards for their immigrant members. Apollonides received a gold wreath worth a thousand drachmas, the right to own property, and the honorary position of proxenos. The right to own property, usually reserved for citizens, would have improved Apollonides’ status in Athens. The monetary award of the gold wreath would have encouraged him to engage in trade activities that would serve Athens’ interests. The honor of serving as a proxenos — an honorary consul legally responsible for Athenian citizens in his home state of Sidon — would have tied him to Athens in an official capacity.

Phoenician professional associations did not only lobby their host state for awards and privileges for their members; they also helped their members maintain their ancestral religious traditions in their new homes. For example, in 333/332 BCE, a group of traders from Kition on Cyprus (modern-day Larnaca) formed a trade association called the “demos of the Kitians” that represented the interests of Kitian traders and the broader Kitian immigrant community living in Athens. As an association, they approached the Athenian state to request the right to own property for the purpose of establishing a sanctuary dedicated to Aphrodite. The Kitians most likely erected a sanctuary to the Phoenician goddess Astarte, the most prominent divinity in Kition, and translated the goddess into her Greek equivalent, Aphrodite. This event is recorded on a large, inscribed stone discovered from Piraeus, the port of Athens, a bustling neighborhood where many immigrants lived. The inscription indicates that the association of Kitian traders presented their request to the Athenian council as a collective and that the Athenians accepted their request. The Kitians subsequently inscribed the decision of the Athenians on a stone and set it up in the courtyard of their sanctuary to publicize the service they performed for their immigrant community.

The Kitians’ choice to build a temple to a deity prominent in their home state indicates their wish to perform their traditional religious practices and retain their civic identity. To do so, they had to petition the Athenian state for a right that ordinarily belonged only to citizens. Similarly, the Herakleistai on Delos, an association of Tyrian traders and shippers, sent an embassy to Athens with a successful request for some land on which to build a sanctuary to Herakles, whose Phoenician equivalent, Melqart, was the patron deity of Tyre. Ultimately, the presence of deities, temples, and priests belonging to the Phoenicians and other foreign groups also changed the physical and social landscapes of the host societies for immigrants and non-immigrants alike. That Greek polities were willing and able to accommodate such requests suggests they were aware of the ways in which host states benefited from the presence of both immigrants and the professional associations that represented them.

The remains of the club house of the Poseidoniasts of Berytus, a Phoenician professional association, on Delos. Ca. 3rd century BCE. Photo by Bernard Gagnon, CC By-SA.

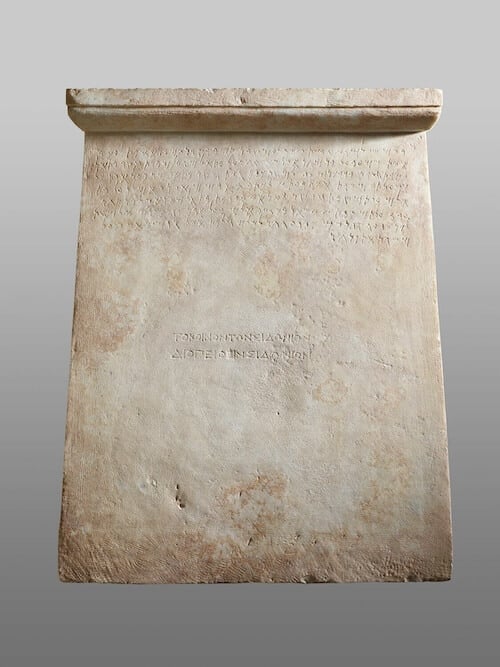

The Phoenician trade associations of 4th-century BCE Athens and 2nd-century BCE Delos acted as autonomous political entities with their own decision-making organs. The phrase used to describe the Kitian trader association, “the Kitian demos,” suggests the group had a political structure and some degree of independence. Similarly, a 4th-century BCE Sidonian association in Athens honored a man named Diopeithes in Greek and Shamabaal in Phoenician because he had benefited the association by outfitting its sanctuary with a court and performing various other tasks entrusted upon him. In the Phoenician text the Sidonian association is described as meeting as an assembly that decided to honor Shamabaal with a golden crown and inscribe this decision on a stele to be displayed in the temple of Baal. The internal organization of the Sidonian association mimicked that of a political entity. By the 2nd-century BCE, trade associations on Delos, like those of the Berytian Poseidoniastai and the Tyrian Herakleistai used several terms to describe the deliberative and decision-making organs of their associations: koinon, synodos, thiasos, ekklesia.

Stele with a bilingual inscription in Phoenician and Greek honoring Shamabaal (Diopeithes), leader of an association of Sidonians in Athens. Found at Piraeus, Greece. Louvre AO 4827. © 2014 Musée du Louvre, Dist. GrandPalaisRmn / Thierry Ollivier.

The structure of Phoenician professional associations, which in essence acted as miniature polities, suggests that these types of organizations had multiple functions. They not only facilitated commerce but also allowed migrants to administer aspects of their lives with some autonomy, even while living under the jurisdiction of their host state. In addition, they enabled immigrant communities to maintain their religious traditions by worshiping their ancestral deities in sanctuaries usually built on land granted to the associations by their host state. Their ability to lobby their host states for awards or petition them for grants bypassed restrictions placed on immigrants, provided them with the opportunity to participate in their host state’s deliberative processes and influence its policies. For their part, host states recognized Phoenician trade associations as having the political standing to make suggestions of a political, economic, or diplomatic nature.

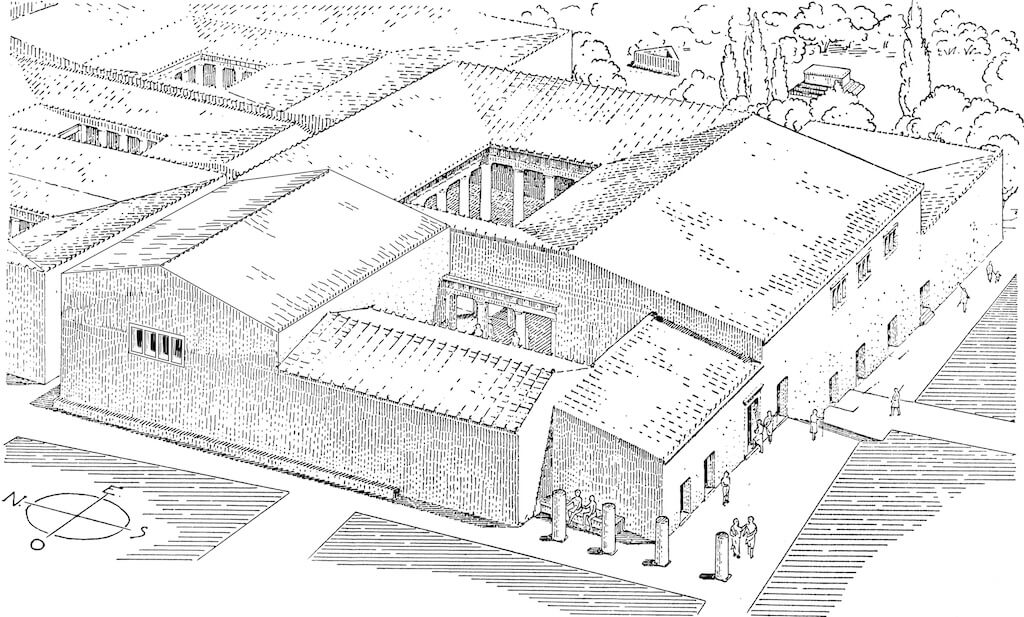

Phoenicians who belonged to professional associations also invested in them. The relationship between associations and their members was reciprocal, as the example of Shamabaal who at his own expense outfitted the temple of Baal in Athens. In investing in their associations, immigrants promoted their home states, maintained their identities, and preserved their cultural traditions. For example, the members of the Berytian association of traders, shippers, and warehouse workers on Delos, known as the Poseidoniastai, made various benefactions that not only supported their association but also promoted their city-state of origin: they refurbished elements of their club house; gave dedications to Poseidon (their patron deity) or their ancestral gods, which acknowledged their ties to their homelands; built altars for religious festivals, etc. Wealthy immigrants like Shamabaal in Athens or the Berytians on Delos helped make it possible for their associations to retain their Phoenician character. They also made it possible for themselves and others from their immigrant community to celebrate their religious traditions and reinforce their ties with their home states.

Preliminary reconstruction of the club house of the Poseidoniasts on Delos, based on Exploration archéologique de Délos faite par l’École française d’Athènes (EAD) Fascicule VI, pl. X. Drawing by Monika Trümper. Used with permission.

Trade associations were Phoenician innovations that emerged because of migration. Like expatriate communities and cultural organizations today (such as the National Hellenic Society; the Alliance Française; or other special interest groups), Phoenician professional associations played an important role in commerce, offered a cultural locus that helped them maintain the religious traditions of their homelands, and they became politically and socially integrated into their host state. As semiautonomous units with assemblies, voting mechanisms, and decision-making processes, these professional associations were incorporated into their host state’s political apparatus, giving immigrants the power to petition their host state and thus participate in its deliberative processes and influence its policies.

Denise Demetriou is a Professor of History and holder of the Gerry and Jeannie Ranglas Chair in Ancient Greek History at the University of California, San Diego. Her book, Phoenicians Among Others: Why Migrants Mattered in the Ancient Mediterranean, was recently published by Oxford University Press.

Further Reading:

Demetriou, Denise. 2023. Phoenicians Among Others: Why Migrants Mattered in the Ancient Mediterranean. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

López-Ruiz, Carolina. 2021. Phoenicians and the Making of the Mediterranean. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Quinn, Josephine Crawley. 2018. In Search of the Phoenicians. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Terpstra, Taco. 2019. Trade in the Ancient Mediterranean: Private Order and Public Institutions. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Want To Learn More?

Maritime Viewscapes and the Material Religion of Levantine Seafarers

Maritime Viewscapes and the Material Religion of Levantine Seafarers

By Aaron Brody

Travel was a liminal experience for Levantine seafarers as they left behind the safety of land and existed in a state of in-betweenness on the water. What kind of religious practices did they develop to cope with the uncertainties of life at sea? Read More

A Sea of Law: The Romans and Their Maritime World

By Emilia Mataix Ferrándiz

The sea was key for Rome’s success, but was also full of danger and risk. How did Roman jurists apply legal principles to deal with catastrophe and loss on the sea? Read More