Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

July 2024

Vol. 12, No. 7

Is it Ethical to Continue Excavating the Dead in the Ancient Near East?

By Lesley A. Gregoricka

Around the world, bioarchaeologists are beginning to come to terms with the ethical ramifications of working with the bodies of the dead. This reckoning has largely been driven by living members of descendant communities, particularly those in the United States under the purview of NAGPRA (Native American Graves Protection & Repatriation Act) as well as by marginalized communities whose ancestors continue to be held by academic institutions and museums without consent (see recent debates on the brains, bones, and other bodies held by the Smithsonian Institution or the bones of MOVE bombing victims at the University of Pennsylvania and Princeton). It must be acknowledged that we do not own the archaeological human skeletons with whom we work, and that without consent from these descendant communities, the skeletons of once-living individuals should not be studied and must be repatriated.

This movement has likewise instigated bioarchaeologists working outside of the United States to more seriously reflect on current practices and procedures surrounding the ways in which we handle the bodies of the dead. However, these considerations rarely include contemplating the first step in this process — the excavation of human skeletons themselves. Today, Near Eastern archaeologists and bioarchaeologists alike continue to excavate and amass ancient human skeletons. Oftentimes, however, little thought has been given to whether we should continue generating such assemblages amidst the existence of already-excavated skeletons — especially those legacy skeletal collections that have not yet been properly curated or analyzed.

Undergraduate students at the University of South Alabama assist with the curation of archaeological human skeletons from a legacy collection. Photo by L. A. Gregoricka.

From a scientific perspective, the human skeleton contains a wealth of information about the life and death of that individual, a direct means by which we can reconstruct aspects of that person as a biological and social being. We can make interpretations about diet, disease, mobility, and activity patterns, all of which (when informed by archaeological context) provide us with a richer understanding of human behavior and the human experience in the past. None of this is in question.

At the same time, we need to be more reflexive about why we excavate in the first place, and ask ourselves if our research goals can be accomplished without disturbing even more human burials. After all, these are not objects or specimens, but people, and as such, must be treated with dignity and respect. Instead of continuing to generate new human skeletal assemblages through excavation, I would urge ANE bioarchaeologists to seek out and rehabilitate understudied legacy or orphaned collections. This is in line with Pamela Geller’s concept of bioethos — to move past the mere acknowledgement of ethics, and instead, to voluntarily and proactively carry out ethical actions, beyond mandated legislative requirements.

The choice to conduct research on skeletal assemblages that have already been excavated — sometimes decades (or more) ago — is not an easy decision to make, particularly as our identities as archaeologists and bioarchaeologists are often tied to our ability to excavate and generate new materials or skeletons with which to work. On the other hand, though, substituting excavation with rehabilitation is equally, if not more, important. It means committing serious time to combing through the field notes of others to re-attach context to these bodies, and to work to properly curate these individuals so that with consent, their skeletons can be studied. If legacy collections can help us to answer similar research questions that we seek to explicate by excavating, we have to seriously consider this as a more ethical option. Alternatively, if we do not have consent from descendant communities to study these skeletons, or if too much context has been lost to make studying them productive, we need to work towards repatriation and reburial, instead of hoarding these once-living people who did not give consent to be excavated or stored in this way.

To be clear, I am not advocating for a moratorium on the excavation of human skeletons. Under the right circumstances — which beyond consent, include an obligation to follow through with a commitment to properly document, curate, and store the assemblages we produce — I still think it’s incredibly important for us to do this as bioarchaeologists. But, it’s also time for us to recognize that we need to take responsibility for our predecessors who accumulated these collections in the first place, and to normalize working with these kinds of collections instead of constantly generating new individuals for study. While legacy collections certainly require us to invest a great deal of time and resources to their rehabilitation, they also hold invaluable information that can be unlocked if we don’t allow our own biases towards such collections to stand in the way.

Lesley A. Gregoricka is a Professor of Anthropology at the University of South Alabama. Her paper, “The Ethics of Excavating: Bioarchaeology and the Case for Rehabilitating Legacy Human Skeletal Collections in the Near East” was recently published in a special issue on ethics in the journal Levant.

Further reading:

de la Cova, C. 2021. Making silenced voices speak: Restoring neglected and ignored identities in anatomical collections. In Cheverko, C., Prince-Buitenhuys, J. R., & Hubbe, M. (eds), Theoretical Approaches in Bioarchaeology (pp. 150-169). New York: Routledge.

Kakaliouras, A. 2012. An anthropology of repatriation: Contemporary physical anthropological and Native American ontologies of practice. Current Anthropology, 53(S5), S210-S221.

Kersel, M. 2015. Storage wars: Solving the archaeological curation crisis? Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies, 3(1), 42-54.

Lans, A. M. 2021. Decolonize this collection: Integrating black feminism and art to re-examine human skeletal remains in museums. Feminist Anthropology, 2, 130-142.

Stantis, C., de la Cova, C., Lippert, D. & Sholts, S. B. 2023. Biological anthropology must reassess museum collections for a more ethical future. Nature Ecology & Evolution, 7, 786-789.

Supernant, K. 2021. Decolonizing bioarchaeology? Moving beyond collaborative practice. In Meloche, C. H., Spake, L. & Nichols, K. L. (eds), Working With and For Ancestors: Collaboration in the Care and Study of Ancestral Remains (pp. 268-280). New York: Routledge.

Thomas, J.-L., & Krupa, K. L. 2021. Bioarchaeological ethics and considerations for the deceased. Human Rights Quarterly, 43, 344-354.

Voss, B. 2012. Curation as research: A case study in orphaned and underreported archaeological collections. Archaeological Dialogues, 19(2), 145-169.

Want To Learn More?

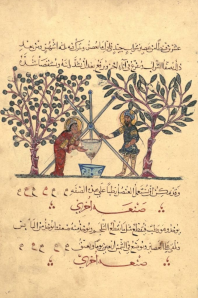

Digitizing Manuscripts from Southwest Asia: Access, Ethics, and Sustainability

By Raha Rafii

Digitization of manuscripts is widely seen as a valuable process that preserves documents and democratizes access. But do digitized manuscripts actually increase access for all potential users? And is digitization as permanent and sustainable as people assume? Read More

Achieving Divinity: “Golden Mummies of Egypt” at Manchester Museum

By Campbell Price

The primary purpose of the ancient Egyptian mummification ritual wasn’t to preserve the mortal body for the afterlife — it was to transform the deceased into a divine being. Read More