Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

June 2024

Vol. 12, No. 6

No One Thought to Ask the Fruits: Revealing Philistines’ Traditions

By Suembikya Frumin

The Philistines (ca. 1200-604 BCE) left no textual sources for understanding their religion, and its study has traditionally been based on external textual sources, such as the Bible. Archaeological research has provided insights into their material culture. However, the Philistines’ cultic practices, calendar of rites, and the hierarchy and relationship between the worshiped deities remain mostly unclear.

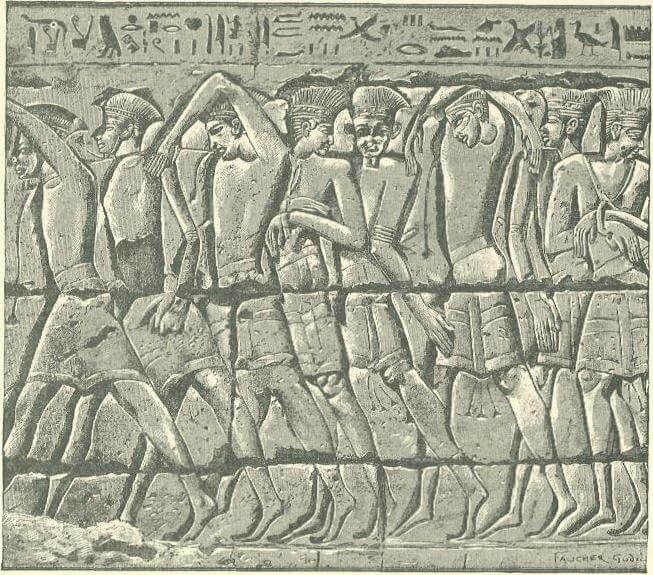

Figure 1. Procession of Philistine captives, relief at the Temple of Ramesses III at Medinet Habu. Drawing by Henri Faucher-Gudin, from History of Egypt, Chaldea, Syria, Babylonia, and Assyria, ed. by G. Maspero (1903–1904). Public Domain.

Archaeobotany — the study of plant finds retrieved from archaeological sites — provides vital direct data for the reconstruction of ancient life and extinct cultures. Fruits and seeds found in votive contexts visualize the type of settlement economy and the role of different crops and wild plants in rituals. Archaeobotanical data accumulated in recent decades show that during the turbulence of the late Bronze and early Iron Age transition, the old Canaanite set of cultivated crops was preserved by the Philistines in what I refer to as a refugium around the Pentapolis cities (fig. 2). A refugium is a biogeographical term for an area where a species (once more widespread) continue to grow and survive, despite regional climatic/landscape changes, or human activities.

The data also show that Philistines actively participated in long-distance trade, as evident from the offering of imported grain pulses and the usage of imported cinnamon and plant-derived oils with hallucinogenic properties for burning in ritual chalices and incense altars. We can also see that the Philistines introduced certain innovations in the use of local wild-growing edible plants.

In a new study on plant-related ritual practices at biblical Gath (Tell es-Sâfī), published in Scientific Reports, a team from Bar-Ilan University (S. Frumin, Aren Maeir, Amit Dagan, Maria Eniukhina, & Ehud Weiss) has been able to provide data that opens a new chapter in the research of the Philistines’ cultic belief and practice. Tell eṣ-Ṣâfī/Gath (famous as the home of mythological giant Goliath) is one of the Philistine pentapolis towns and is situated in the Shephelah phytogeographic region — a fertile, hilly region that interconnects the coastal and mountain regions. Our study analyzed plant finds from two temples built on top of each other, one dated to the tenth century BCE and the other to the ninth century BCE. The plant finds retrieved from various parts of the temples were identified up to the species level and the phytogeography of each species was evaluated to identify the probable area of its cultivation/growth. For the first time, the research reveals crop- and wild plant-related activities in Philistine temple compounds throughout the entire annual cycle. The difference in plant finds between the two subsequent temples was assessed to evaluate the possible season in which the latest of these temples (and the city) was destroyed by Hazael of Aram Damascus (ca. 830 BCE).

Plants and Cult Practices at Gath

The archaeobotanical study of the Philistine temples at Gath revealed new data concerning the functionality of the temples and their cultic practices. First, we observed the temples were kept clean and there was no sign of communal crop storage/offering. Rather, the presence of charred but complete (unprocessed) seeds of crops, such as wheat, grape, lentils, etc., indicate ritual burnings of samples of harvested products. Also, the presence of one silo, a clay oven, and grinding stones in the temple courtyards suggest that food was prepared in situ and this food was a component of cultic practice. Beyond these, the finding of strainer spout jugs inside the temple suggests the offering and consumption of various fermented foods. Besides crops, the plant assemblage includes evidence that the temple personnel were knowledgeable regarding the use of plants with mood-affecting features. Indeed, considering that the temples were kept clean, it is noteworthy that the temple assemblages include plants with a history of pharmacological use, such as bitter vetch, chaste tree, golden daisy, and poison darnel. These finds also provide the first-known case of the connection of crown daisy and scabious to cultic depositions, and the earliest example of the chaste tree’s cultic use.

Poison darnel (Lolium temulentum) is a weed of wheat and a host for ergot — a parasitic fungi containing an LSD-type alkaloid, known to be hallucinogenic. Its chemical properties have been known since antiquity, and it was used both by midwives and as a fortifying ingredient in brewing. The use of ergot in cultic contexts as a psychoactive is mentioned in ancient sources in connection with the Greek Eleusinian Mysteries, which were associated with cults of agriculture. Bitter vetch (Vicia ervilia), an edible and medicinal plant, is associated with the Talmudic (second century CE) borit karshina — a type of lye which is listed in the incense offerings (and proposed to be a conserving ingredient) used in the Tabernacle and the First and Second Temples in Jerusalem.

Among the edible plants found in the temples, all were of typical local agriculture, with no seeds or fruits of exotic, imported crops, indicating the importance of local agriculture for the settlement economy and culture. Yet, one plant foreign to the Shephelah region occurred by the altar. This gromwell species (Buglossoides incrassata) — a weed of cereals and pulses — currently does not occur in the Shephelah, and thus sheds light on the crops trade (fig. 3). This plant is a rarity in the neighboring Judean Mountains and the Samarian Desert, yet common in northern Transjordan and on Mount Hermon. Notably, the gromwell was found along with crops and other weeds near a jar from the Jerusalem area. This suggests that Philistines used traded staples for offerings from Judah and from other regions.

Figure 3. Map of the natural area of distribution of Buglossoides incrassata in the southern Levant – green squares mark locations of the species observation. Image from Danin, A. & O. Fragman-Sapir. 2016+, Flora of Israel and adjacent areas. https://flora.org.il/en/plants/buginc/

Seasonality of Cultic Rites

Considering the reconstruction of the seasonality of rites, crop phenology reveals that freshly harvested crops could be offered almost year-round, since their harvests span from the end of March (barley) till the end of October and into December (olive harvest for oil production). Grain staples and fruits such as grapes, figs, and olives can be stored dry for extended periods and therefore can be offered at any time. Therefore, the presence of crop plants among the botanical remains cannot help us pinpoint the time of year of the dedications.

Luckily, beyond crops, the temple plants included wild plants, edible only when green, and thus gathered for use while fresh. The earliest (seasonally) among the wild plants are the crown daisy (Glebionis coronaria; fig. 4) and cheese weed (Malva parviflora); they both flower from February to May. These two species were found in both temples and therefore signify the continuous significance of this season and its natural events, such as the end of winter/early spring, for the Philistine rites. Moreover, the shape of the Aster family inflorescences, and the crown daisy in particular, resembles the well-known “rosette” motif. This flower motif is widespread across the Late Bronze Age Mediterranean, as well as in Iron Age II Philistia, Judah, and Mesopotamia. We propose that the similarity with the shape of the “rosette” was apparent for the gatherers of crown daisies for the temples (fig. 5).

Figure 4. Crown daisy in bloom. The petals of the crown daisy can be white or yellow with a yellow crown in the center. Photo by the author.

Figure 5. “Rosette plaque”, ca. 1175 BCE. We believe the rosette device so popular in the eastern Mediterranean in the late Bronze Age and Iron Age was inspired by the crown daisy. Photo courtesy of Princeton University Art Museum (object number y387b)

Two other species are found only in the last temple of Gath, providing data for the reconstruction of the last rites held there and possibly for the time of the city invasion by Hazael. These are lilac chaste tree (Vitex agnus-castus) and lovegrass (Eragrostis minor). Lilac chaste tree (fig. 6) is a large shrub common in places with a high water table with flowers starting from the middle of summer, i.e. the end of June, when most plants in the local flora are not in bloom. Its fruits were found among the miniature vessels and other cultic paraphernalia deposited in the cella. Lovegrass is a wild cereal, grains of which were found inside a storage jar intermixed with grape pips and linseeds. Lovegrass ripens from September to January, so these may have been brought to the temple somewhere around September. Considering the presence of both lilac chaste tree and lovegrass, this indicates that the city of Gath was destroyed in the late summer/early autumn.

Figure 6. Chaste tree: leaves and inflorescence. Photo by the author.

The discovery of around one hundred chaste tree fruits found in the last temple is unique in its abundance in Israeli archaeobotany data. Such a large amount indicates that it was brought for bedding or for decorating the offerings. According to Dioscorides and Nicander, the chaste tree was known as a medicinal (snake bite antidote) and was used as an abortifacient. Notably, chaste tree fruits were part of the cargo of the Late Bronze Age Uluburun shipwreck (late 14th century BCE), revealing that they were valued during that time. During the Iron Age, there is direct and written data for the significance of the chaste tree in the Heraion on Samos during the sixth-third centuries BCE. The plant was also used at the female agricultural festival of Thesmophoria, an ancient Greek festival in honor of Demeter and her daughter Persephone. The cult of Artemis Orthia (Lugodesma, eighth-sixth centuries BCE) in Sparta was associated with this plant. Later, according to Pausanias, the wooden image of Asclepios (Agnitas) at Sparta was made from the chaste tree.

These historical data for the cultic role of the chaste tree are later than the Philistines’ temples at Gath, so no direct connections can be made between them. Nevertheless, the quantity of the plant that was found in the Philistine ritual context is unique in the Levantine archaeological record and therefore is salient. All the cults mentioned above relate to freshwater / purity, fertility, and rejuvenation, which suggests that we should see a connection between the rituals at the temples at Gath and the nearby river. Also, the symbolism of the cults allied with the chaste tree accords with numerous female figurines in Philistine contexts, which have been identified as connected with widespread cults of the Aegean or Mycenaean Great Mother Goddess. Connections between Aegean and Philistine cults have been noted before, but this new data from Gath determine the first such connection that relates to plant use in cultic contexts.

In sum, the plant assemblage from the temples at Gath indicates, for the first time, that the Philistines’ cultic praxis included the worship of early spring. This involved symbolic rites held in the temples involving a wide variety of crops and wild plants (including daisy and chaste tree), along with the consumption of food with mood-enhancing ingredients, prepared by its knowledgeable personnel.

Suembikya Frumin is Laboratory Manager at the Prof. Ehud Weiss Lab for Achaeological Botany at Bar-Ilan University. She is the lead author of “Plant-related Philistine ritual practices at biblical Gath”, recently published by Scientific Reports.

Further reading:

Dagan, A., Eniukhina, M. and A. M. Maeir. 2018. Excavations in Area D of the lower city: Philistine cultic remains and other finds. Near Eastern Archaeology 81 (1), 28-33. https://doi.org/10.5615/neareastarch.81.1.0028

Frumin, S., Maeir, A., Eniukhina, M., Dagan, A., and E. Weiss. 2024. Plant-related Philistine ritual practices at biblical Gath, Scientific Reports 14, # 3513. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-52974-9 (open access)

Frumin, S. 2022. Cereal and Fruit Plants of the Philistines – Signs of Territorial Identity and Regional Involvement, Journal of Eastern Mediterranean Archaeology and Heritage Studies JEMAHS 10 (3-4): 259-286. https://doi.org/10.5325/jeasmedarcherstu.10.3-4.0259

Frumin, S., Maeir, A. M., Horwitz, L. K. and E. Weiss. 2015. Studying ancient anthropogenic impacts on current floral biodiversity in the Southern Levant as reflected by the Philistine migration. Scientific Reports 5, 13308. https://doi.org/10.1038/srep13308

Weiss, E. and M.E. Kislev. 2004. Plant remains as indicators for economic activity: a case study from Iron Age Ashkelon. Journal of Archaeological Science 31(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-4403(03)00072-4

Want To Learn More?

The Wheat From the Chaff: What We Can Learn From Studying Plants in Antiquity

By Jennifer Ramsay

Archaeobotanists have spent decades refining methodologies for the recovery, identification, and analysis of plant remains from the archaeological record. So what can charred bits of plants tell us about the natural and cultural landscapes of the past? Read More

Maritime Viewscapes and the Material Religion of Levantine Seafarers

Maritime Viewscapes and the Material Religion of Levantine Seafarers

By Aaron Brody

Travel was a liminal experience for Levantine seafarers as they left behind the safety of land and existed in a state of in-betweenness on the water. What kind of religious practices did they develop to cope with the uncertainties of life at sea? Read More