Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

June 2024

Vol. 12, No. 6

Ancient Near Eastern Rulers and their Delegations in 18th Dynasty Egyptian Tombs

By Mohy-Eldin E. Abo-Eleaz

The victories of Pharaohs in their northern campaigns during the first half of the 18th Dynasty earned Egypt’s rulers entrance into a brotherhood of Great Kings who recognized Egypt’s great status. In the reign of Thutmose III, the kings of Babylonia, Cyprus, Assyria, and Ḫatti began to court the Pharaohs to strengthen their alliances. In the famous annals of Thutmose III, the arrival of the embassies to meet the king and his army, as well as the list of gifts carried by each of them, are presented as signs of respect from the donors, showing the sincerity of their intentions. Not only did such embassies communicate with Pharaohs while on campaign, but they also appear to have reached the Egyptian court with relative frequency.

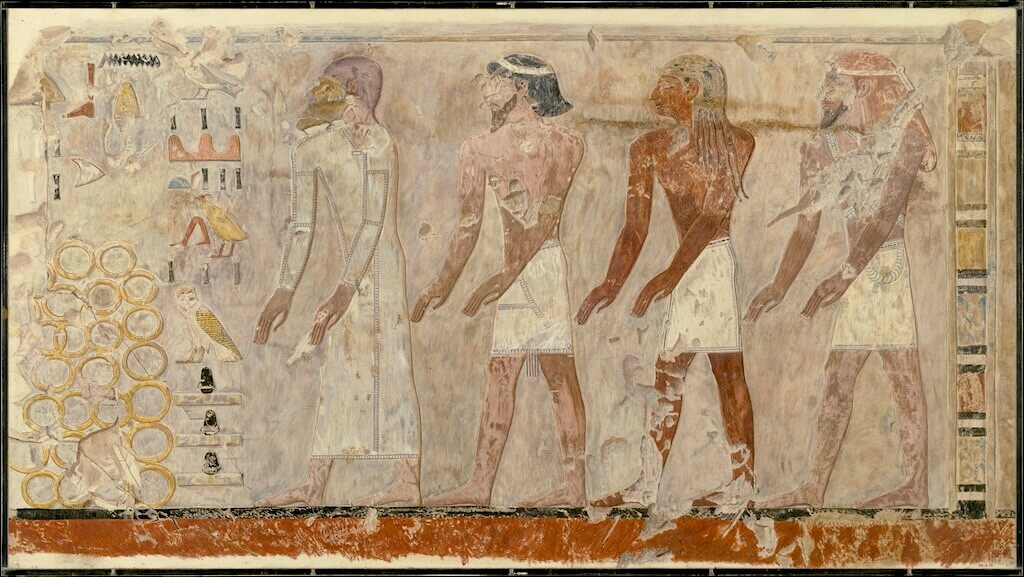

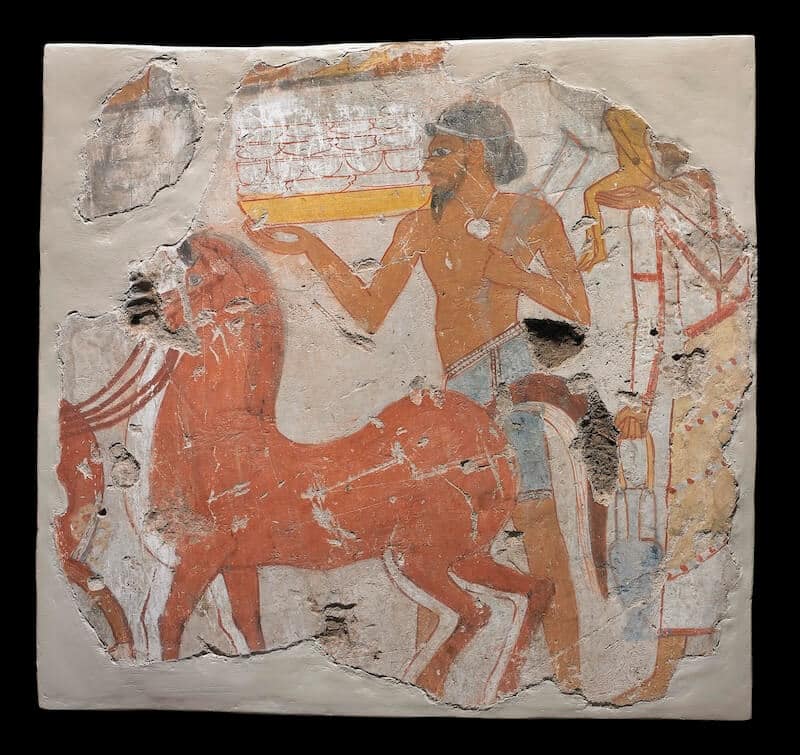

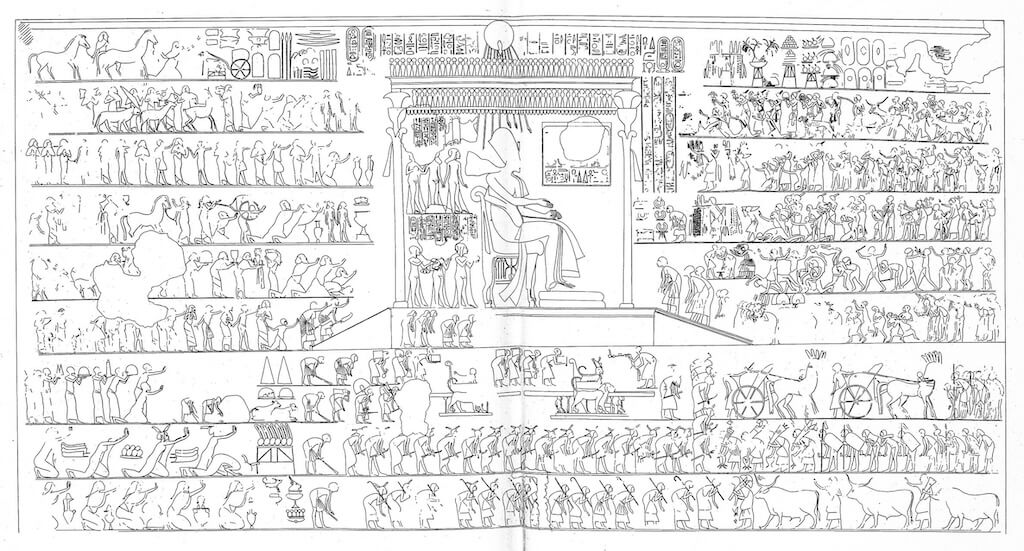

Facsimile of a painting from the tomb of Puimre (TT39; reign of Thutmose III): Four foreign rulers show their respect at the Egyptian court. Painting by Norman de Garis Davies (1915), held by the Metropolitan Museum of Art (30.4.13). Public Domain.

The names of those countries were typically recorded in the royal annals. At the same time, Egyptian royal officials also bragged about these visits, memorializing the arrival of foreigners and their tribute through scenes in their tombs. A typical caption reads:

Giving praise to the Lord of the Two Lands, making obeisance to the Good God.… They extol the victory of his majesty, their gifts (ı̉nw) upon their backs, namely every product of God’s land: silver, gold, lapis lazuli, turquoise, and every precious stone so that the breath of life might be given to them. (Translation from E. Morris, Ancient Egyptian Imperialism (2018). John Wiley & Sons).

Foreigners are depicted in no less than fifteen private tombs from the 18th dynasty. The most frequent foreigners shown in these scenes are Levantines, Nubians, and the Aegeans. Within each register there is generally a hierarchical ordering of people and objects according to the Egyptian ideological worldview. At the front of the delegation is the most important figure, usually designated as “wr” in Egyptian, which is often translated into English loosely as “chief” or “prince”; it is thought that the wr is the local ruler. Following him are other men in varying attire. Behind the men are the women and children, who follow the animals that the men in front of them carry or lead on a leash.

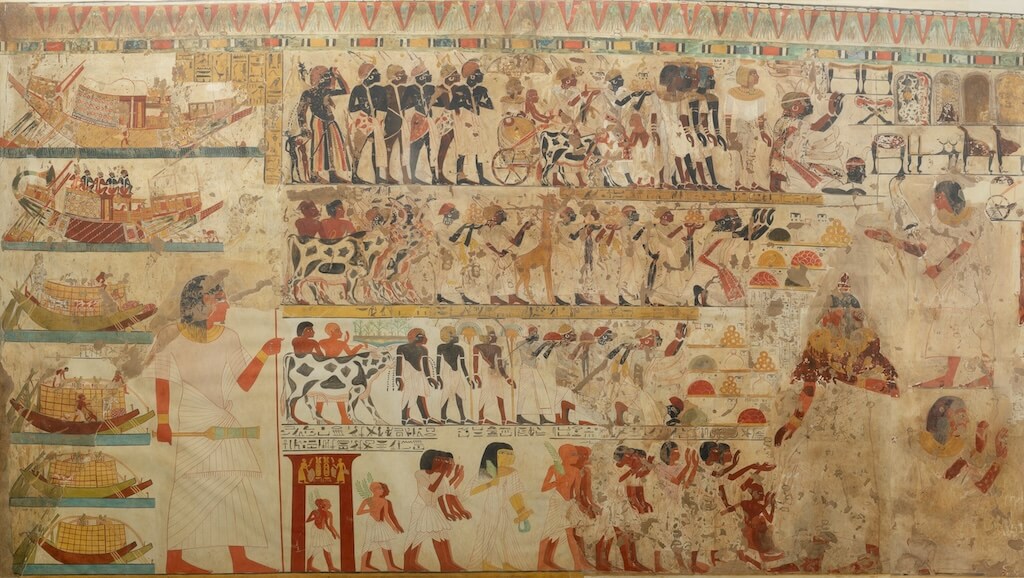

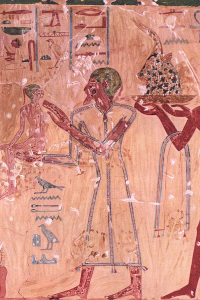

Rulers of Nubia accompanied by their entourage present gifts and pay homage to the Pharaoh. Tomb of Huy (TT40), ca. 1353–1527. Facsimile painting by Charles K. Wilkinson. Metropolitan Museum of Art 30.4.21. Public Domain.

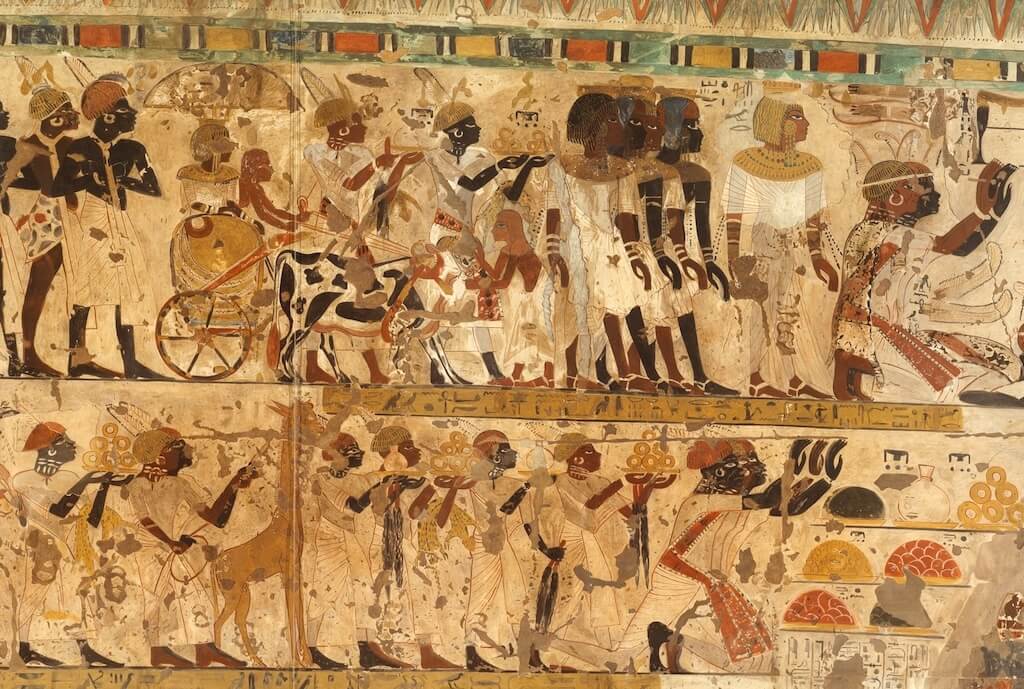

Now, let us search for these foreign rulers in those scenes of the tombs of Thebes. In the tomb of Menkheperreseneb (TT 86), dated to the later reign of Thutmose III, there is a large scene depicting the occasion of the New Year’s Festival. The upper register is dedicated to the Syrian and Aegean figures. The first figure of the first register is prostrating and accompanied by a text identifying him as “chief of Keftiu wr n Kftjw” (Crete). The Annals of Thutmose III record Aegean diplomatic gift–giving in year 42, when the “Prince (wr) of Tanaja ” (the name used for the Greek land) sent silver and copper gifts. The following two figures are also Syrian figures identified by their accompanying texts as “chief of Ḫatti” (wr n Ḫt[ȝ]) and “chief of Tunip” (wr n ṭnpw).

Facsimile of a painting from the Tomb of Menkheperraseneb (TT86) depicting Aegean and Syrian rulers at the court of Thutmose III. The third figure from the left is the prince of Tunip presenting his son to the court. Painting by N. M. Davies, published in Ancient Egyptian Paintings Vol 1, Pl. 21. University of Chicago Press, 1936. Courtesy of the Institute for the Study of Ancient Cultures of the University of Chicago.

Also depicted in the scene above is the chief of Tunip bringing his son and presenting him to the court. One of the ways that Thutmose III endeavored to maintain control over his empire with a minimum use of force was by having chiefs bring/send their children and their brothers to be detainees in Egypt; and whenever any of these chiefs died, the Pharaoh would have the son/brother return home to assume his position. This practice was embraced by other late 18th–Dynasty rulers as well. Amenhotep III boasted of this practice, and the presence of foreign heirs at court is also attested in the Amarna archive.

A chief from western Asia presents his son (fragmentary figure on right), preceded by a tribute bearer. Tomb of Sebekhotep (treasury official in the reign of Tuthmose IV). British Museum EA37987. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Iamnedjeh, the “overseer of the gate” under Thutmose III, gave a prominent place in his tomb (TT 84) to the theme of foreign delegations. They are depicted presenting their gifts to the Pharaoh during the ceremonial appearance of the king in the palace of Heliopolis at “the beginning of the year” (tpy rnpt). The right-side of the wall commemorates in two registers the presentation of a Syria-Palestinian delegation to the gifts. One of the two prostrating figures of the lower register is named with the superscription as “chief of Naharin ” the most common Egyptian designation for the land of Mitanni).

In some other tombs, foreign ruler figures and their emissaries are represented bearing different objects and piling them in front of Egyptian officials themselves; this is attested in the tombs of Puimre (TT 39), Amenmose (TT 42), Sobekhotep (TT63), Senenmut (TT 71), Amenemheb (T T 85), Rekhmire (TT 100), Useramun (TT131), Intef (TT 155), and (TT119).

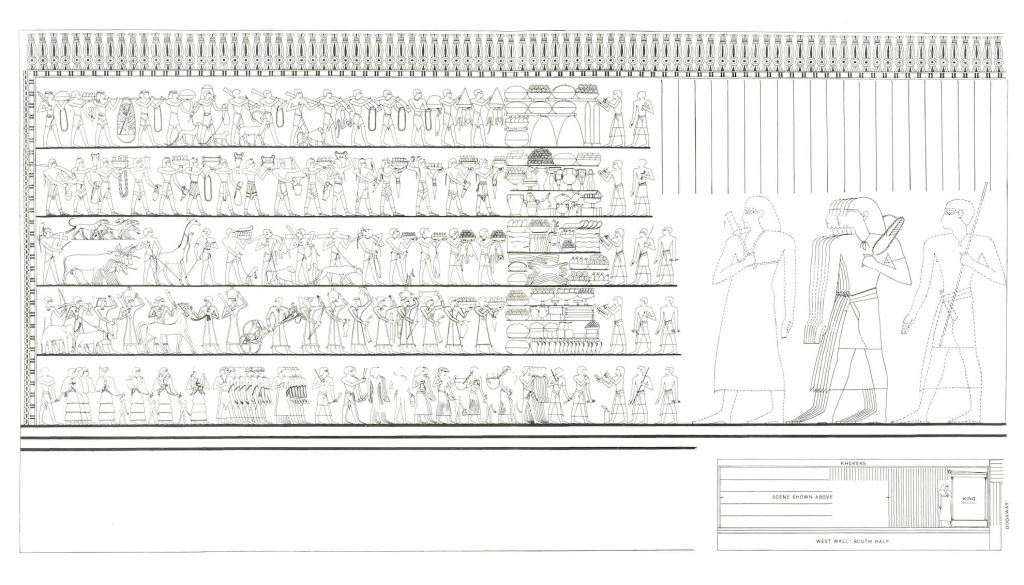

Rekhmire (vizier under Thutmose III and Amenhotep II) receives tribute and gifts from the “great ones” of Punt, Crete, Nubia, and Syria-Palestine. Drawing of a tomb painting from the Tomb of Rekhmire (Thebes, TT100). By Norman de Garis Davies, Paintings from the Tomb of Rekh-Mi-Re at Thebes (1943), Pl. XXII. © Metropolitan Museum of Art. www.metmuseum.org.

Two pairs of men in western Asian dress do obeisance to Sebekhotep, followed by men carrying vessels, some gold and inlaid with precious stones. Tomb of Sebekhotep (Thebes, TT63; reign of Thutmose IV). British Museum EA37991. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

Evidence dating to the late 18th Dynasty period is less abundant but continued to be celebrated during the reign of Akhenaten, even though this king has been criticized by many scholars for his negligence of foreign affairs. Two sets of scenes from the Amarna tombs of Meryra II (AT2) and Ḫuya (AT1) commemorate the gifts ceremony celebrated in the 12th regnal year of Akhenaten, whereby the king received foreign delegations from the Levant.

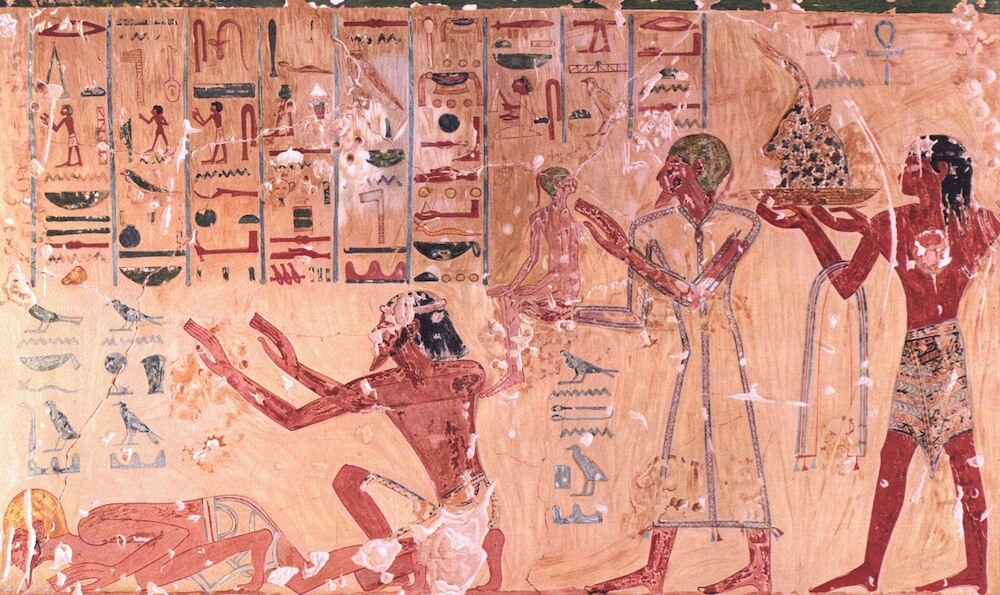

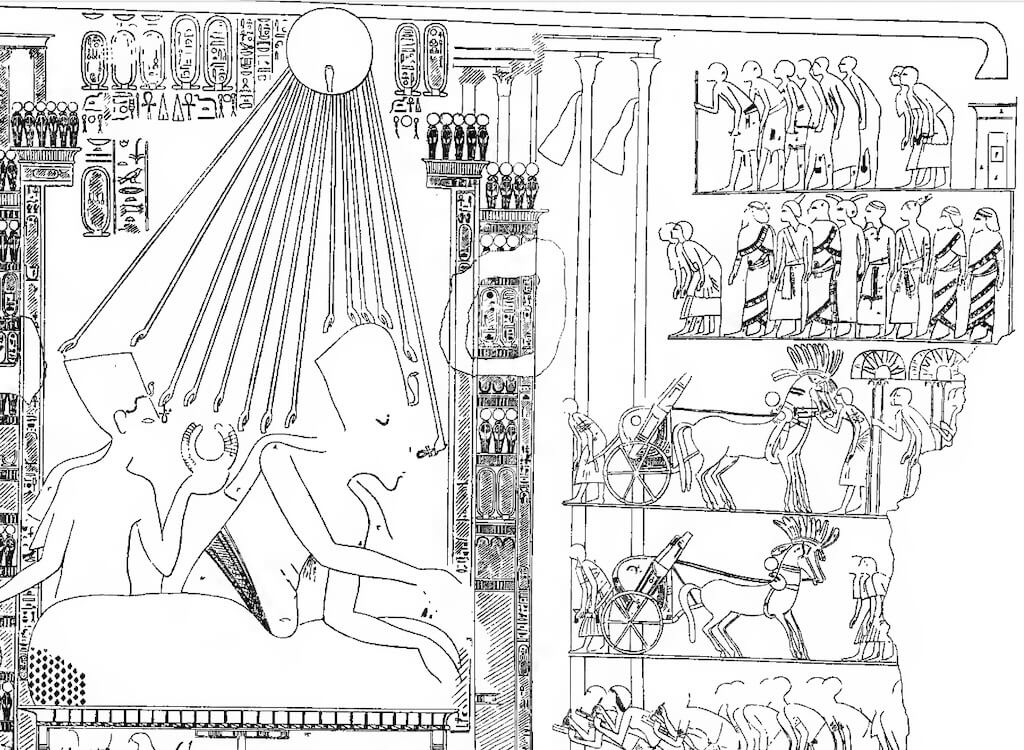

The presentation of gifts and tribute ceremony, celebrated in the 12th regnal year of Akhenaten. Drawing by N. de G. Davies, The Rock Tombs of El Amarna: Part II: The Tombs of Panehesy and Meryra II (London, 1905), pl. 37. Public Domain.

Foreigner delegations in the presence of Akhenaten and Nefertiti at the “Awarding of Gold” ceremony. Drawing from N. de G. Davies, The Rock Tombs of El Amarna: Part III: The Tombs of Huya and Ahmes (London, 1905), pl. 33. Public Domain.

The depiction of foreigners at Akhenaten’s court indicated an interest in making his court appear cosmopolitan, and indicates continuity with the practices of his 18th dynasty predecessors. This is despite accusations of negligence by his Levantine vassals and the prevailing scholarly opinion that he lacked interest in foreign affairs.

It seems that this tradition continued until the end of the 18th Dynasty, as there is a scene of Libyan and Asian envoys bowing and scraping before Horemheb. However, after the end of the 18th dynasty, scenes of foreign chiefs and their delegates carrying gifts to the Egyptian king disappear from the repertoire of private tomb decoration.

Foreign envoys from Libya and the Near East bow and scrape before Horemheb. Relief from his tomb in Saqqara, ca. 1333–1323 BC. Photo courtesy of the National Museum of Antiquities, Leiden. CC0 license.

Mohy-Eldin E. Abo-Eleaz is Associate Professor of History and Civilization of Egypt and Ancient Near East at Minia University.

Further reading:

Abo-Eleaz, Mohy-Eldin E., 2019. Face to face: Meetings between the kings of Egypt, Ḫatti and their vassals in the Levant during the Late Bronze Age, Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 48: 1-21.

Abo-Eleaz, M.-E. E. 2021. “The reward of the pharaohs: Egyptian royal grants and gifts for the rulers of Canaan in the Amarna letters.” Antiguo Oriente 19: 65-112.

Anthony, F. B. 2016. Foreigners in ancient Egypt: Theban tomb paintings from the early Eighteenth Dynasty. Bloomsbury.

Panagiotopoulos, D. 2006. “Foreigners in Egypt in the time of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III.” In: Cline, E.H.; O’Connor, D. (eds.), Thutmose III. A new biography. University of Michigan Press, 370-412.

Want To Learn More?

Understanding Trade and Power in Early Egypt: A Geopolitical Approach

by Juan Carlos Moreno García

International trade is closely tied to the organization of power in Egypt, but it isn’t all about the royal court. Rather, commercial activity sometimes flourished when monarchies collapsed. Read More

The Harsh Life of Diplomatic Messengers in Egypt in the Late Bronze Age

By Mohy-Eldin E. Abo-Eleaz

Diplomatic messengers in the Late Bronze Age had to endure numerous difficulties to accomplish their missions. But from the surviving correspondence, it seems that Egypt may have been the most hazardous posting of all. Read More