Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

May 2024

Vol. 12, No. 5

The Hebrew Bible and the Meanings Ruins Hold

By Daniel Pioske

On April 28, 1462 CE, Pope Pius II issued a bull (Cum almam nostram Urbem) prohibiting the destruction of Roman ruins on penalty of excommunication. As one of the first recorded attempts to safeguard ancient remains, the injunction was put into effect, Pius II writes, to preserve the beauty of ruins not yet disturbed in the city and to better appreciate the ancient virtues that led to their construction. More importantly, however, Rome’s ruins were to be conserved because they conveyed the fragility of all human undertakings (rerum humanarum fragilitatem), their dilapidated forms demonstrating that even the great works of the powerful rulers of old could not withstand the corrosive effects of time.

View of the so-called Temple of Concord with the Temple of Saturn, on the right the Arch of Septimius Severus, by Giovanni Battista Piranesi. 1760-78. Metropolitan Museum of Art 2012.136.916. Public Domain.

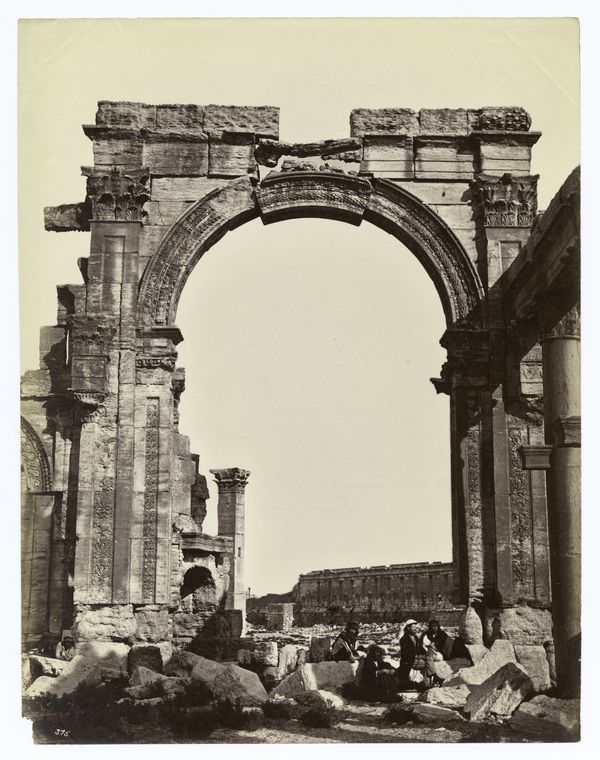

Three centuries later, Constantin-François de Chasseboeuf, comte de Volney, would write a famous work, Les Ruines (1791 CE), set amid the venerable remains of Palmyra. One evening, Volney reports, a phantom appeared from one of the antiquated tombs found at the site. The spirit, aware of revolutions abroad, counsels Volney that the downfall of a people can be averted by enlightened statecraft and the judicious governance of its leaders. The banks of the Seine did not have to succumb to the ruined landscape Palmyra had become.

Two accounts of ruins, two distinct descriptions of the meanings they convey. A lesson that can be drawn from these reflections on ruination is that the values we attribute to material remains are neither uniform nor timeless. Rather, ruins have given rise to an array of impressions over the centuries, the connotations ascribed to them shaped in response to the eras in which they are realized. To the humanist and Renaissance pontiff, ruins attested to both the heights of what ancient forerunners had achieved and the fallenness of the human condition; to Volney, a member of the newly formed National Constituent Assembly, ruins served as a warning of what awaited societies corrupted by attachments to regimes and institutions now obsolete.

Ruins of Beth-Shean on the mound in the background with ruins of Scythopolis in the foreground. Photo by Daniel Pioske.

But if the meanings we assign to ruins take on distinct expressions across the ages, then how did people in antiquity experience the remains they, too, encountered? One of the richest historical sources we possess on this question is the Hebrew Bible, a corpus in which ruins are referred to frequently and among nearly every scroll that would come to be contained within its canon. The Hebrew Bible is in many ways a book of ruins, written in a world where wreckage and loss, or the threat thereof, were common. From the famous accounts of the fall of Jericho or ‘Ai (Josh 6, 8) to the anguished descriptions of Jerusalem’s ruins after its Babylonian conquest (e.g., Ps 79; Lam 2; Jer 44), we are offered insights into how those behind the formation of these texts valued the material remains that we know, archaeologically, were embedded in the landscapes they held in view.

When we turn to these ancient accounts, what is striking is that we do not come across a single passage that expresses an interest in unearthing the ruins referred to. Instead, material remains provoked different responses. Above all, ruins conveyed something about time to the biblical writers who refer to them. At moments, ruins were connected to a world of forerunners and of events that had come to pass long before these texts were written down. In the Book of Jeremiah, for example, the prophet directs his contemporaries to visit the ruins of Shiloh and remember what had once transpired there (Jer 7:12; 26:9), though the destruction of the location, we are told elsewhere in the biblical writings (Ps 78:60-64), would have occurred well over four hundred years before. In other texts, anonymous storytellers direct our attention to ruins that could be encountered “to this day,” such as in the story of Rachel’s Tomb in the Book of Genesis (Gen 35:20). There we read that after Rachel’s postpartum death, “Jacob set up a pillar over her tomb; it is the pillar of Rachel’s tomb to this day” (הוא מצבת קברת רחל עד היום). What comes to the fore in passages such as these is a present haunted by the remains of former times, harrowed by figures bound to the ruins that remained. Most frequently, however, ruins in the Hebrew Bible are affiliated with a time yet to come. This prospective sense of ruination is typically associated with the city of Jerusalem and a destruction that a collection of biblical texts, especially among the prophetic writings (eg., Micah 3:12; Jer 22:1-10; Ezek 5), foresee and forewarn. Much like Volney’s meditation on Palmyra, when these texts refer to ruins they perceive material remains as harbingers of possible futures to come.

Excavations on Ophel, Wall of the Jebusites, Jerusalem. American Colony (Jerusalem), c. 1900-1920 CE. G. Eric and Edith Matson Photograph Collection. Library of Congress, Prints & Photography Division, LC-DIG-matpc-05478. Public Domain.

In stepping back from these ancient texts, what is apparent is how different their sense of ruination is from our own. That ruins could disclose something about the time ahead, for example, stands in clear opposition to how ruins are understood historically today. Rather, we historians and archaeologists are predisposed to think of material remains in terms of what they convey about the lived experiences of ancient populations who once inhabited them. The moment we label an artifact as “Late Bronze Age II” or locate it within an assemblage dated to the “4th century BCE,” we have entered a universe of assumptions about time and ruins that the biblical writers did not share. To put it differently: the prospect of digging down through space to journey back in time is an idea so common to us that we rarely reflect on how we came to hold it or how it departs from those who experienced ruins in the centuries before.

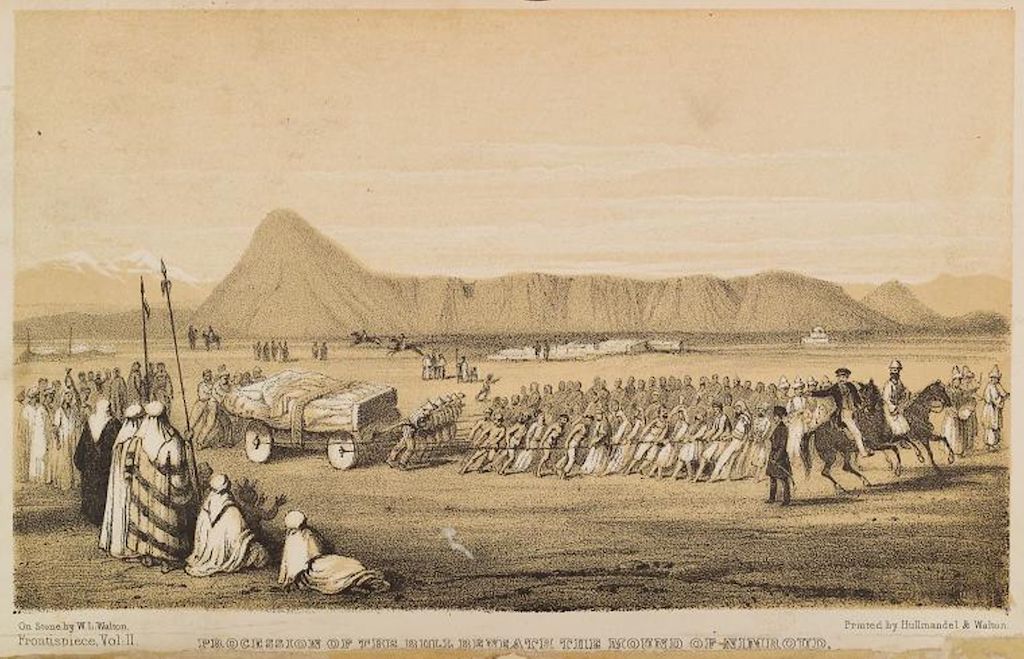

“Procession of the bull beneath the mound of Nimroud.” Frontispiece from Volume II of Nineveh and Its Remains by A.H. Layard (1849); Lithograph by W.L. Watson. Image: The New York Public Library Digital Collections (OCLC 700101). Public Domain.

The ruins have not changed, but the way we look at them has. This is a shared insight also found in Peter Fritzsche’s investigation of ruination and the French Revolution, Susan Stewart’s work on ruins and the early modern period, and Julia Hell’s study of mimesis and the ruins of the Roman Empire. Alongside these eras and their conceptions of ruination, the Hebrew Bible, too, I argue, offers a vantage point by which to consider how those still further back in time and outside of European lands perceived the ruins they encountered. But to tell the histories of these encounters and attend to the meanings ruins once held, it is perhaps necessary to also turn the looking glass around and ask what it is about us and our time that we experience ruins as we do, excavating their remains in ways none of our predecessors did before. Why, that is, do we dig?

Daniel Pioske is Assistant Professor of Theology at University of St Thomas, Minnesota. He is the author of The Bible Among Ruins: Time, Material Remains, and the World of the Biblical Writers (Cambridge University Press, 2023).

For Further Reading:

Peter Fritzsche, Stranded in the Present: Modern Time and the Melancholy of History. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2004.

Julia Hell, The Conquest of Ruins: The Third Reich and the Fall of Rome. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2019.

Daniel Pioske, The Bible Among Ruins: Time, Material Remains, and the World of the Biblical Writers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2023.

Susan Stewart, The Ruins Lesson: Meaning and Material in Western Culture. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2020.

Constantine-François Volney, Les Ruines, ou Méditation sur les Révolutions des Empires. Paris: Desenne, 1791.

Want To Learn More?

Are Possession and Other Spirit Phenomena Depicted in the Hebrew Bible?

By Reed Carlson

Many scholars rule out the presence of spirit phenomena in the Hebrew Bible. Reed Carlson explains why this is a mistake. Read More

(Re)visiting the Past in the Present: The Power of Place and the Malleability of Monuments

By Matthew D. Howland, Morag M. Kersel, James F. Osborne, and Yorke M. Rowan

Archaeology aspires to reveal the layered meanings of ancient places. Can studying contemporary urban landscapes help us better understand monuments and the power of place in the Ancient Near East? Read More