Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

February 2024

Vol. 12, No. 2

Jewish Experiences in the Roman Bathhouses of Judaea/Syria Palaestina

By Yaron Z. Eliav

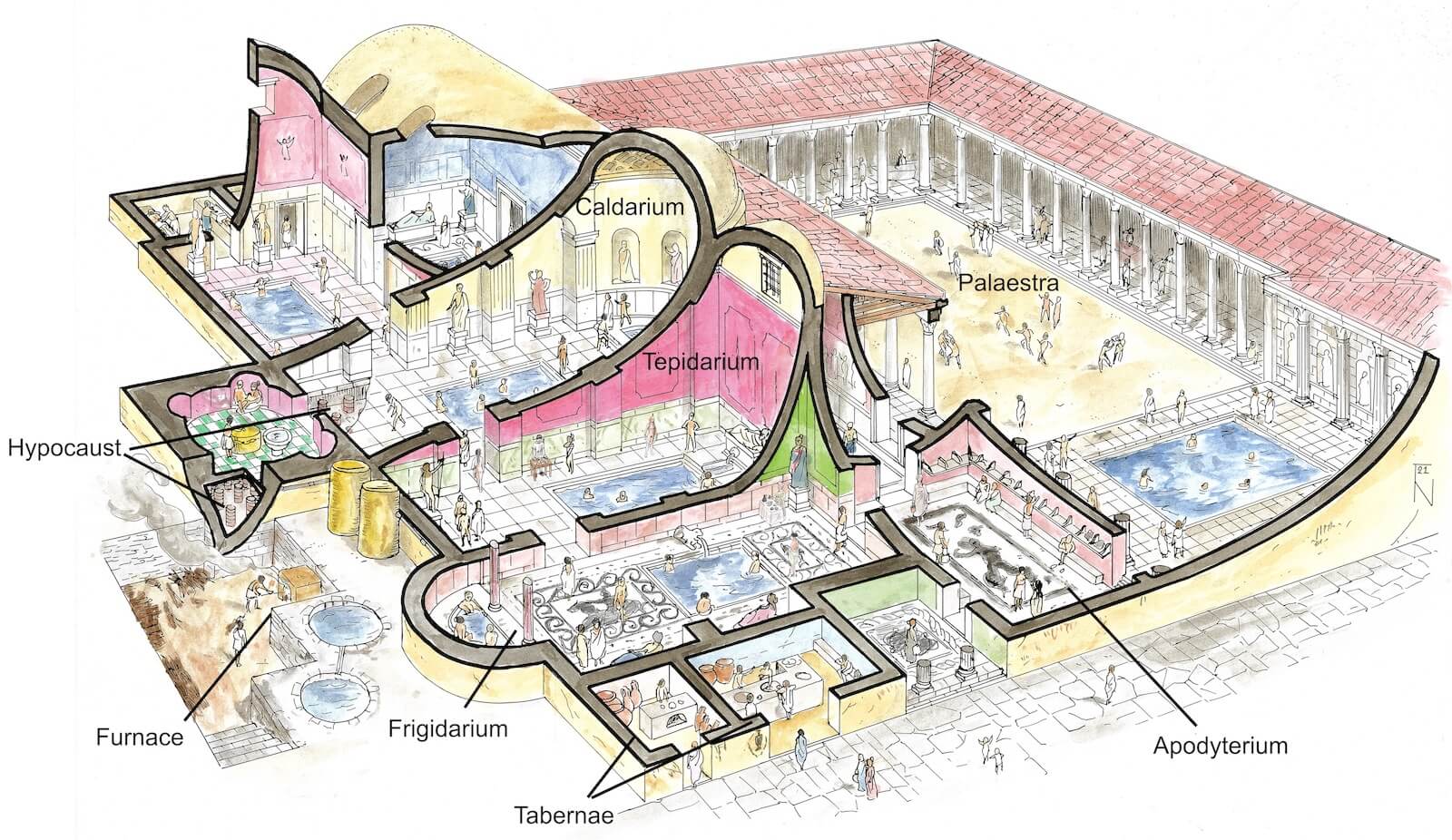

The Roman public bathhouse was an impressive architectural complex, featuring both hot and cold water installations as well as a wide range of other services — a sauna and massage parlors, swimming pools, open courts for recreation and sports, gardens, meeting rooms, food and oil stands, and at times even libraries and brothels. No other space within the ancient world embodied so many different features of the Roman way of life (known as romanitas): everything from engineering and architecture to food and fashion, from sculpture to sports, from nudity and sex to medicine and magic, to name just a few. Ideas about the human body, science, religion, and metaphysics, life and its carnal and spiritual pleasures, as well as concepts about fate, aesthetics, social hierarchy, and imperialism, all manifested themselves in the physical environment of the baths, and the daily experience of attending them. In an empire that extended from modern England and Spain to Egypt and Iraq, residents of the empire erected bathhouses in sprawling cities and small villages alike. And people from all walks of life visited them, both wealthy and poor: prominent citizens and ordinary, men, women, children, as well as household slaves, all came in droves, usually every day. The Jews were no different.

In the first few centuries of the common era, hundreds of thousands of Jews lived in the Roman province called Judaea (which, during the second century, became Syria-Palaestina, or simply Palestine). A wide variety of ancient sources document the Jewish life that transpired in this region: archaeological remains such as synagogues and the art (mainly mosaics) displayed within them; documentary papyri and inscriptions; as well as literary segments devoted to Jews in the writings of Graeco-Roman and then Christian authors. But the richest evidence comes from the collection of texts known today as rabbinic literature, a group of some forty documents of various sizes produced between the 3rd and 7th centuries by the figures we now collectively call “rabbis.” This huge latter corpus of ancient writings — indeed, the largest group of Jewish texts that survived from Roman times — repeatedly alludes to public bathhouses: with over five hundred references to the baths and associated activities, the bathhouse is the best represented Roman institution in rabbinic material! Modern investigators have mostly ignored this treasure trove of information, partially because of linguistic obstacles — rabbinic texts generally employ Aramaic and Hebrew, languages outside the sphere of most classical experts — and also because of the entrenched misconception that the Jews in general, and the rabbis in particular, were an isolated community detached from the Roman world.

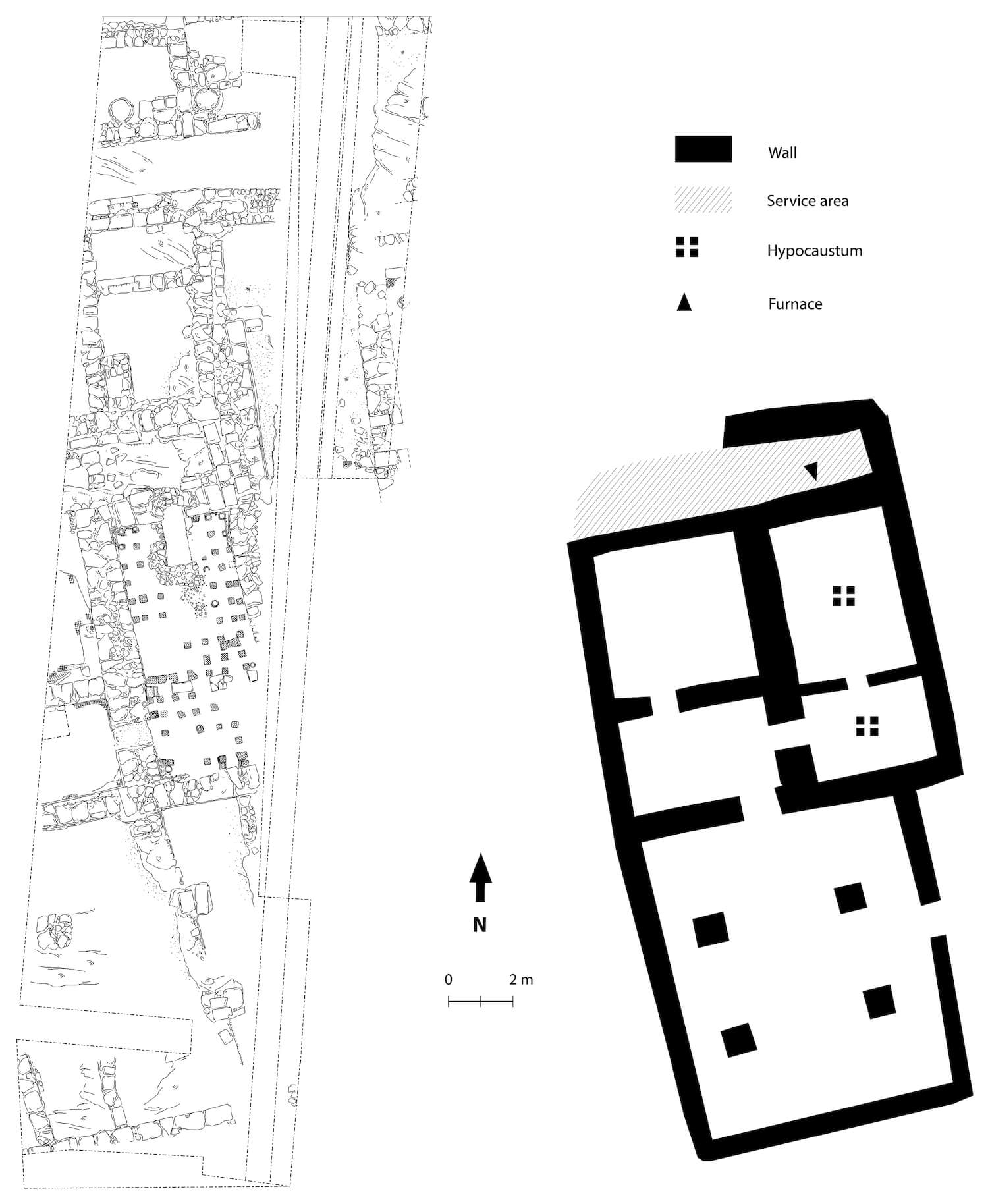

It is time to overcome this blindspot. Even before the days of the rabbis, both archaeological evidence and the writings of Flavius Josephus, the Jewish historian from early Roman times, attest to the existence of Roman bathing establishments in Jewish settings as far back as the closing decades of the first century BCE. Archaeologists have unearthed them in the palaces of King Herod (most notably in Masada and Herodium), as well as in Jewish cities and towns such as Magdala in lower Galilee, or the remains of a Jewish settlement, name unknown, just north of Jerusalem, located today in the grounds of the modern Palestinian neighborhood and refugee camp of Shuafat. Josephus alludes to one such bathing facility in a story he tells about the Jewish town of Isana, some twelve miles north of Jerusalem. Other Jewish sites in the western intermediary region known as the Sheffelah also feature well-designed public baths from the late first and early second centuries CE. From the second century on, the picture that emerges from rabbinic material and that is supported by archaeological findings shows numerous bathing establishments in every city, town, and in many cases even in the smallest of villages, of Roman Palestine.

It is clear that Jews frequented Roman bathhouses like all other residents of the Mediterranean world. But how did they feel about the lifestyle and experiences that were customarily partaken in these institutions, many of which seem (to our modern eyes) diametrically opposed to Jewish norms? To name a few: Men and women attended these facilities together. Everyone left their clothes in changing room cubicles near the entrance to the building (known in Greek as the apodyterium, and in rabbinic terminology as “the room of the ’olyarin”), and strolled the baths mostly or fully naked. Needless to say, all this resulted in a promiscuous atmosphere and licentious behavior, well documented in Graeco-Roman and rabbinic sources alike. In addition, many bathhouses contained Roman statues, often of Greek and Roman divine figures, adding an idolatrous dimension that would seem quite damning for Jews, let alone rabbis.

And yet, Jews used the baths. Understanding this seeming contradiction forces us to rethink some of our most fundamental assumptions about these people and their way of life. The evidence is as unequivocal as it is surprising. Rabbis frequented the baths and cherished their pleasures like everyone else in the ancient world. The sheer volume of evidence is impossible to ignore. Large numbers of anecdotes and traditions place rabbinic figures in bathhouses — not merely passages where rabbis discuss matters regarding the baths, or comment on an aspect related to their function and operation, but rather depictions (whether real or imagined) or references to rabbinic figures in public bathhouses. Numbers do not lie. Certainly, not all the traditions about rabbis visiting the baths are historically accurate, nor are they intended to be. Nevertheless, they convey the mindset of the authors who composed and transmitted these anecdotes. These rabbinic texts took it for granted that all rabbis (and by extension, most if not all other Jews as well) went to the public bathhouses, and, more importantly, that they loved it there. Indeed, some rabbis explicitly pronounce their appreciation and affection for the bathhouse and its amenities. They also articulate guidance to help Jews manage aspects of the baths that seemed to infringe on Jewish law, in matters such as the Sabbath, ritual purity, the sabbatical year and more. Combined, these rabbinic expressions take the bathhouse for granted, and view it as an integral part of Jewish life.

In my current book — A Jew in the Roman Bathhouse: Cultural Interaction in the Ancient Mediterranean — I identify a subtle cultural process — which I call “filtered absorption” — that explains the interaction between Jews and Roman baths. In order to live as part of the Roman world while also maintaining their heritage and unique practices, Jews and rabbis continually identified and assessed features of their surroundings that were inconsistent with their convictions and way of life; these elements were then either rejected altogether or more often reframed to adapt to Jewish norms. This process of cultural negotiation, subversion, and appropriation was messy: never consistently regulated, never uniform, with great variation by time and place. But at the end of the day, filtered absorption allowed (at least some) Jews to live in peace with the surrounding culture, which from this perspective was also their culture. Rabbinic literature, and its abundance of views on the bathhouse and the activities that transpired within its walls, allows us to follow these dynamics, at least partially, and to explore the strategies and mechanisms at work as they took shape within the Jewish world. Far from promoting exclusivity and isolation, I see the rabbis and their literary corpus as engaging in a relentless process of cultural negotiation and appropriation.

Yaron Z. Eliav is Associate Professor in the Department of Middle East Studies at the University of Michigan. His book, A Jew in the Roman Bathhouse: Cultural Interactions in the Ancient Mediterranean, was recently published by Princeton University Press.

Want To Learn More?

Horvat Midras (Israel): A Window into Socio-Religious Change in Rural Roman Palestine

By Orit Peleg-Barkat and Gregg E. Gardner

The rural areas of the Southern Levant are traditionally understudied by archaeologists, but recent excavations at Horvat Midras offer fresh insights into the changing ethnic and religious character of this complex region. Read More

Baths of the Roman and Byzantine Southern Levant: Roman Ideas and Local Interpretations

By Arleta Kowalewska and Craig A. Harvey

Bathhouses are one of the most iconic remains of the Roman world. So what do we know about baths and bathing in the southern Levant under Roman rule? Read More