Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

June 2023

Vol. 11, No. 6

The Book of Esther as a Source for Achaemenian History

By Morteza Arabzadeh Sarbanani

The Book of Esther (fig. 1) is set in the Persian capital of Susa during the reign of Xerxes (Ahasuerus in Hebrew) and tells the story of how a young Jewish woman living in Persia becomes queen. Most modern scholars consider the Book of Esther to be a kind of historical novel and have debated its historical value by comparing the book with classical sources. But what if we do a close reading while comparing also to non-Greek sources? In a recent article, I argue that a significant part of the historical material of the Book of Esther is in line with evidence that most of the classical sources are unaware of. This independence from the Greek sources makes the Book of Esther more important as a historical source for Achaemenian history than has traditionally been assumed. What follows is a brief discussion of some verses that contain historically relevant information, much of which is not found in the Classical sources.”

Esther 1:1 & 3:12. In Esther 1:1 we find reference to “127 provinces” of the Achaemenian empire, which many scholars have assumed refers to the satrapies. However, the Hebrew word for provinces used here, medinot, in the Hebrew Bible mainly refers to small districts of a small kingdom such as Israel or larger parts like the province of Judaea. And in Esther 3:12, the author makes a clear distinction between “the king’s satraps” and “the governors over all provinces”. This suggests the “provinces” in Esther 1:1 are not equivalent to the satrapies but the smaller divisions that comprised the satrapies, which would explain why the author has used such a large number. Esther 1:1 also refers to the eastern and western boundaries of the Persian Empire as marked by India and Ethiopia, respectively. This description is both chronologically and geographically accurate: in the time of Xerxes I, India and Ethiopia were part of the Persian Empire and are included in a contemporary list of subject nations (XPh 25 & 28, the “Daiva Inscription.”

Esther 1:3. This verse speaks of a banquet in Susa in the third year of Xerxes’ reign. A loan document from Susa (but found in Babylonia; Vorderasiatische Schriftdenkmäler IV, 191) dated to the third year of Xerxes’ reign confirms that he was in Susa on that time. We also know that Xerxes had subdued the Egyptian rebels by January 484 BC, therefore, the feast mentioned in the Book of Esther may have been a celebration of Xerxes’ victory over Egypt.

Esther 1:14. This verse mentions the seven counselors of the Great King who are described as having “access to the king” and “sat first in the kingdom”. Other Jewish and Classical sources have also spoken of such officials with elite status (e.g. Ezra 7:14; Xenophon, Anabasis, I.6.4). This theme of a number of officials or counselors (not necessarily seven) close to the Great King is echoed in the Behistun inscription (fig. 2), where Darius the Great mentions by name the six men who helped him to secure the throne. These men were later given special privileges such as coming into the king’s presence without announcement (Herodotus, III, 118). It is not unreasonable to assume that such positions continued in successive generations.

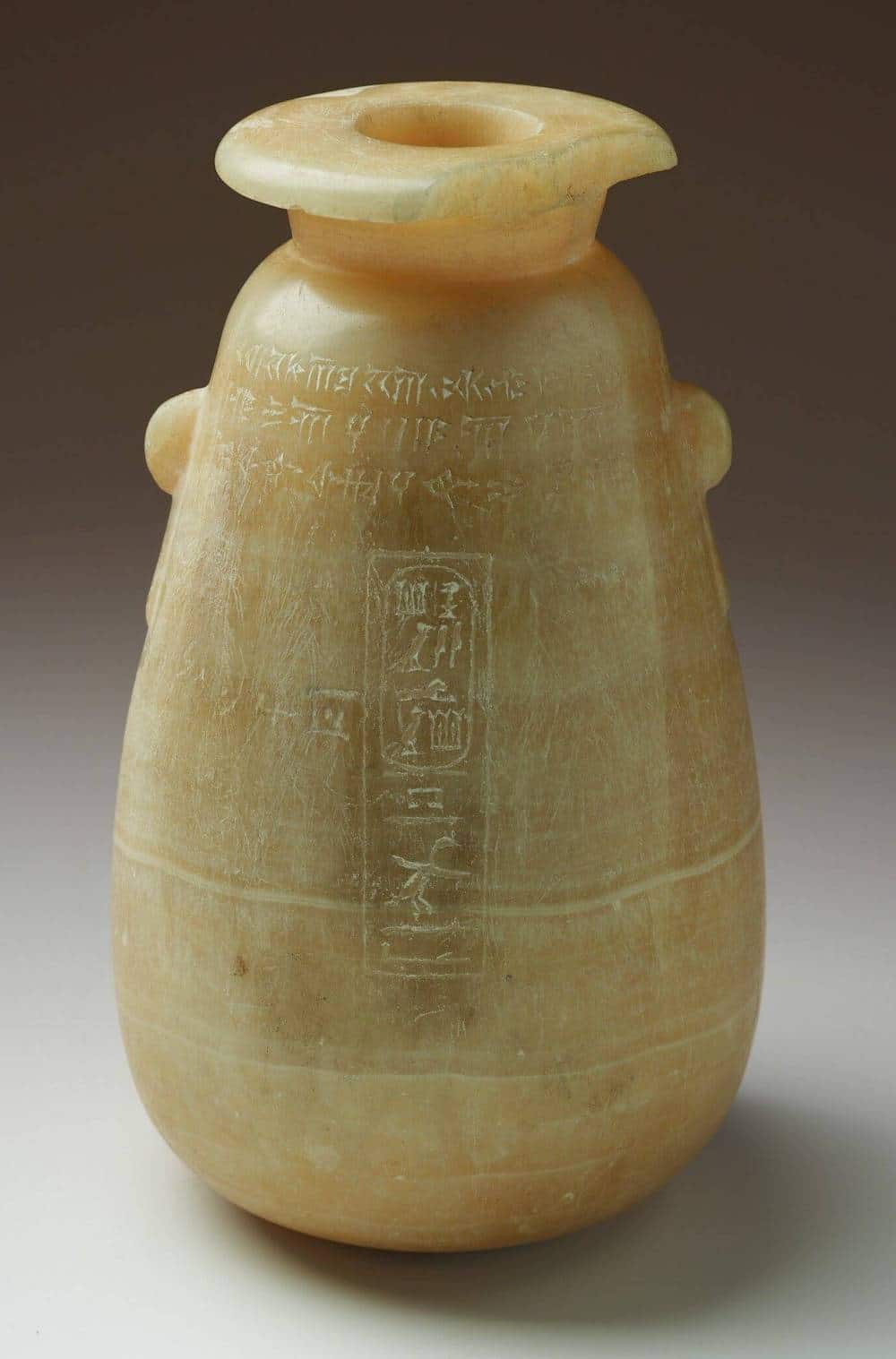

Fig. 3 Vase with the name “Xerxes the Great King” written in Old Persian, Elamite, Akkadian, and Hieroglyphs. Yale Babylonian Collection 2123. Height 22.5 cm. Image © Yale Babylonian Collection

Esther 1:19. The Hebrew word dat meaning “law” that occurs in this verse is originally derived from the Old Persian dāta with the same meaning. This term passed into the language of many peoples of the Persian Empire (including the Jews) in semantic contexts beyond the native Jewish, Mesopotamian and other conceptions of “law”. The irrevocability of laws of the Persians and Medes mentioned in this verse actually refers to the extreme strictness of the Persian rulers regarding the execution of laws. For example, Darius the Great in the Behistun inscription has indicated the terrible fate of delinquents (DB, §32, §33).

Esther 1:22. This verse describes how Xerxes sent out an edict to different parts of the empire, “to each people in their own language”. This is totally in line with the multilingual nature of the Achaemenian Empire. The Behistun inscription mentioned above is well known for its trilingual composition. And while Aramaic acted as a lingua franca, other languages and scripts such as Babylonian, Old Persian, Elamite, Demotic, Egyptian hieroglyphic, Greek, etc. were also used in different parts of the Empire (fig. 3).

Esther 2:21-23: These verses tell the story of how Mordecai (Esther’s guardian) uncovered a plot against the king. The two eunuchs involved were hanged and the whole affair was recorded, we are told, in “the book of annals” in the presence of the king. Herodotus (VIII, 85) also attests to a practice of recording the names of “benefactors” on a special list; these individuals received gifts as reward for having performed important service on the king’s behalf (cf Herodotus III, 140). The whole episode also echoes Darius’ statements in the Behistun inscription: “the man who was excellent, him I rewarded well; (him) who was evil, him I punished well” (DB,§8.1.20-22).

Esther 5:2: This verse speaks of the golden scepter of the king and its use in the audience ceremony, describing how the King extends the scepter towards Esther for her to touch it. In the reliefs in Persepolis, the Great King is shown enthroned and holding a long scepter in his right hand (fig. 3). We cannot deduce how the scepter was employed ceremonially based on these reliefs alone, so the account by the book of Esther provides a useful idea for how it might have been used.

Esther 1:3; 1:14; 1:18; 1:19; 10:2: These verses all reference the close connection between the Persians and Medes at the Achaemenian court (fig. 5). This Persian-Median coupling in the book of Esther is echoed in the Achaemenian royal inscriptions. Ten inscriptions contain lists of countries. In one inscription in particular (DPg), Darius the Great presents himself as “king of Persia, Media and other countries”. The special mention of Media to the exclusion of other lands indicates its special status. The importance of Media is reflected in the other country lists as well: in three of them (DSe, Dna, XPh) Media appears as the first, in four of them (Dsab, A2Pa, Dne, Dpe) as the second and in one of them (Dsaa) as the third country.

Fig. 5 The Persian and Median soldiers on a relief from Persepolis: Not only in the Jewish and Greek sources, but also in the reliefs of Persepolis, the deep connection between the Persians and Medes can be seen.

So what do all these verses tell us? They show that the author of MT Esther was well acquainted with the administrative system of the Persian Empire. He was aware of the division of the empire into several satrapies and the division of the satrapies into smaller administrative units (Esther 1:1; Esther 3:12). He knew that among all of the countries of the empire, Persia and Media held the most prominent position (Esther 1:3; 1:14; 1:18; 1:19; 10:2). He understood the importance of the imperial laws, the strictness of the government in their implementation (Esther 1:19) and also the multilingual character of the empire (Esther 1:22). He was also informed about Achaemenian political history. For example, he knew exactly how large the empire was in the time of Xerxes I and that Xerxes I was in Susa in the third year of his reign (Esther 1:1; Esther 1:3). He had also good knowledge of the Achaemenian court customs. For instance, he was aware of the seven counselors of the Great King (Esther, 1:14), the function of the golden scepter (Esther 5:2) and the record of benefactors (Esther 2:23).

Although some of this information has resemblance to that provided in Classical sources, most of it is in line with evidence directly connected to the Persian Empire. Considering this fact along with the absence of any Greek word in the text on the one hand and the presence of many Old Persian and Aramaic words on the other hand, it seems that the author of the Book of Esther had access to sources directly related to the Persian Empire.

This raises another question, and that is the origins of the countless historical errors of the Book of Esther. Although this is not the concern of the present piece, one possible answer could be that the author made those mistakes deliberately to compose the story. In other words, the author of MT Esther was conscious of the historical errors, but he did not modify them for the sake of the drama of the story. For him, the story was more important than history and he used the historical data only to convince his readers of the historicity of the story.

Morteza Arabzadeh Sarbanani holds a Master’s Degree in ancient Iranian history from the University of Tehran. His article, “Revisiting the Book of Esther: Assessing the Historical Significance of the Masoretic Version for the Achaemenian History” recently appeared in the journal Persica Antiqua.

Want To Learn More?

Breaking the Code: Ancient Iran’s Linear Elamite Script Deciphered

By François Desset, Kambiz Tabibzadeh, Matthieu Kervran, Gian Pietro Basello, and Gianni Marchesi

There are few remaining Near Eastern writing systems left to decode. But the Linear Elamite script has eluded scholars, until now. Previously known names of kings and deities were key. Read More

The Care of the Elderly in Susa: A Study in the Akkadian Documents from the Sukkalmah Period

The Care of the Elderly in Susa: A Study in the Akkadian Documents from the Sukkalmah Period

By Hossein Badamchi

A unique series of texts from the early second millennium BCE at Susa shows that care of the elderly was a serious concern for families. Then, as now, inheritance was a motivation for children to provide their parents with proper care. Read More

Aramaic Poetry: A Window into Jewish Life in Late Antiquity

By Laura S. Lieber

We know very little of the lived experiences of the majority of Jews in late antiquity. But insights can be teased from the literary traces of the early synagogue. Read More