Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

May 2023

Vol. 11, No. 5

A Sea of Law: The Romans and Their Maritime World

By Emilia Mataix Ferrándiz

The sea was key for Rome’s success; it served as the setting of several battles that granted them hegemony over the Mediterranean as well as the main highway for both ideas and commerce. However, human bodies are not naturally suited to the sea; entering or crossing it means challenging one’s own capacities in the face of the power of water. The latter is echoed in literary sources, which often focus on the sea’s enormity and wilderness, thus evoking — and sometimes even exaggerating — its aura of mystery and uncertainty and the effect it has in ancient societies.

Roman legal sources, on the other hand, tend to focus more on the practical challenges and effects of interacting with the sea, presenting a different vantage point from which to study how Romans regarded and dealt with the challenges presented by the sea. So what can we say about how Roman jurists perceived the sea? Although jurists coincide in their understanding of the sea as a dangerous realm not governed by their civil law, the solutions which they provided for similar problems vary from jurist to jurist and from one period to another.

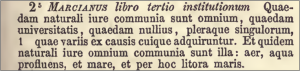

Marcian’s fragment compiled in Justinian’s Digest (6th century CE). Extracted from Theodor Mommsen’s editio princeps from 1889

In the Roman world, spaces were governed by different legal fields. While the land was managed by ius civile (the law of Roman citizens), the sea was a space of ius gentium, or the law of all peoples. It was the jurist Marcian (second–third century CE), who wrote that the sea was the common property to all according to natural law. From his writings the main point to note is that the sea is not subject to an individual’s dominion and, therefore, is also not subject to Roman governance. Despite Roman imperialistic aims and propaganda, it is unlikely that the ideology of rule over land and sea extended to any practical attempts to regulate the use of the sea.

In their texts, Roman jurists reflect on different kinds of sea-storm situations, to which they then apply legal institutions in order to organise and provide solutions to catastrophes suffered by people in what was considered a space free from the rule of Roman civil law. In these contexts, shipwrecks appear as events that bridge the gap between land and sea, because of the different legal remedies provided to deal with such catastrophes, which in turn enlarged the scope of land-based legal rulings. Civil law remedies were often applied to events that happened onboard ships, which is probably because even if the Roman jurists did not phrase it in that fashion, they—as happens nowadays—considered ships as extensions of the land, and therefore as spaces where the civil law of the Romans could apply.

The Roman ship Isis Geminiana depicted in a fresco from the 1st century CE. Vatican Museums. (Photo by the author)

A similar parallelism traced between sea and land can be appreciated when the jurists address piracy. But in this case, the different ways of dealing with these dangers respond to the historical contexts in which the Romans operated. The pirates’ abuses in the first century BCE led to the promulgation of several rulings (e.g. Lex de piratis persequendis, 100 BCE), which legally justified that combating pirates was an obligation of all countries, which then was the perfect justification for the Romans to cross borders and jurisdictions of other countries. However, the danger of piracy was reduced to a local level during the Empire (when the whole world was under Roman authority), so there was no point in maintaining the idea of the international prosecution of piracy. As a result, Roman law from that period made no distinction between piracy and robbers on the land.

Delphi Copy, Block B. lin 8-12

ὁμοίως τ]ε̣ καὶ πρὸς τὸν βασιλέα τὸν ἐν τ̣[ῇ ν]ήσῳ Κύπρωι βασιλεύοντα καὶ πρὸς τὸν βασιλ[έα τὸν ἐν Ἀλε]-|ξανδρείαι καὶ Αἰγύπ̣[τωι βασιλεύοντα καὶ πρὸς τὸν βασιλέα τὸν ἐπὶ Κυ]ρήνῃ βασιλεύοντα καὶ πρὸς τοὺς βασιλεῖς τοὺς ἐν Συρίαι βασιλεύον[τας, πρὸς οὓς] | φιλία καὶ συμμαχία ἐ[στὶ τῶι δήμωι τῶι Ῥωμαίων, γράμματα ἀποστελλέ]τω καὶ ὅτι δίκαιόν ἐστ̣[ιν αὐ]τοὺς φροντίσαι, μὴ ἐκ τῆς βασιλείας αὐτ[ῶν μήτε] τῆ[ς] | χώρας ἢ ὁρίων πειρατὴ[ς μηδεὶς ὁρμήσῃ, μηδὲ οἱ ἄρχοντες ἢ φρούραρχοι οὓς κ]αταστήσουσιν τοὺ[ς] πειρατὰς ὑποδέξωνται, καὶ φροντίσαι, ὅσον [ἐν αὐ]τοῖς ἐσ[τι] | τοῦτο, ὁ δῆμος ὁ Ῥωμαίω[ν ἵν’ εἰς τὴν ἁπάντων σωτηρίαν συνεργοὺς ἔχῃ.

((— And likewise) to the king who reigns in the island of Cyprus and the king (who reigns in) Alexandria and Egypt (and the king) who reigns in Cyrene and the kings who reign in Syria (who) have a relationship of friendship and alliance (with the Roman people (he) sends letters) (in which it is said) that it is right that they take care that from their kingdom (or) from their territory or from their borders not (depart) (any) pirate ( and that the magistrates or the commanders of garrisons that (they) designate give asylum to the pirates, and that (they) take care, as far as this (it will be possible), that the Roman people ((them) have (as) coadjutors for security of all.)(transl. Braga, 33, in Italian, transl. English author)

The Lex de piratis persequendis (100 BCE) in one inscription from Delphi found between 1893 and 1896.

One of the main problems that one faces in case of suffering a wreck and surviving it is that of recovering their cargo. Jurists focused their attention on two main points. First is the presumption that things lost in a wreck are not abandoned, but lost, and thus still legally belong to the original owner. Second is the question of whether something recovered from the sea or washed up on the shore could be considered as definitively lost by the owner. In that regard, it is important to consider that the act of casting cargo overboard to balance the ship in case of danger (as indicated in the famous Lex Rhodia) was not usually carried out by the owner but by the shipmaster or their crew, and therefore it was assumed that this could not be conceived of as abandonment. Goods lost at sea were items separated from their natural destiny and were thus not susceptible to acquisition by natural ownership (occupatio). However, these could perhaps be salvaged from the bottom of the sea. In that sense, we know about the existence of paid divers (urinatores) who were in charge of recovering lost cargoes. Their intervention is visible in some wrecks, and it is clear that their activity influenced legal issues concerning the consideration of cargoes as lost or abandoned.

Madrague de Giens (France). Wreck from 75/60 BCE from which ancient urinatores have recovered amphorae of Veveio Pappo, abandoning river pebbles used for the descent to the seabed. Source: CNRS and centre Camille Julian.

Thus, when dealing with the recovery of a cargo, the principles established by Roman jurists may look clear, but the reality is that the situations change from case to case and each instance had to be evaluated individually. To get a better understanding of the phenomena at hand, Roman jurists also decided to establish legal analogies with land cases. Cargoes lost at sea were then compared to wild beasts (which initially belong to no one but can be tamed) or domesticated animals (that are the property of their owners). Therefore, the discussion here focused on when one can be considered to have lost ownership of one’s own animals, such that these can be appropriated by someone else, or when one can be considered to have ownership over a wild animal. From these angles, it might seem that there are some clear similarities with things lost from a wreck, since one of the key questions here is when these animals become susceptible to acquisition by others.

An example of this is a certain excerpt from Ulpian’s work (third century CE), in which the jurist refers to a case in which somebody’s pigs were snatched by wolves, but were successively saved by the courageous intervention of a neighbour, who pursued the predators with his hounds (Digest 41.1.44 (Ulpian 19 ad Ed.)). Ulpian states that ownership cannot be lost as long as the thing that has been taken away, in this case a pig, is a domestic animal. Therefore, the original owner had the right to recapture the snatched animal. The text concludes by analogy (a common tool used by jurists to explain legal principles) that what is lost in a shipwreck does not cease forthwith to be ours.

The issues analysed here underline, on the one hand, the self-limits established by the Romans when handling legal problems arising from the vagaries of the natural world. Curiously enough, one might be surprised to see how a Mediterranean power such as Rome was still confined in some respects by the enormity of the sea, relying on legal remedies corresponding to land matters. This seems to characterise Rome as the agrarian power that it was known to be in their origins. On the other hand, what emerges from the issues discussed here are examples of how the Roman jurists worked within relatively narrow conceptual categories to obtain solutions to broader problems. In the Roman world, although the rule of the sea was a complicated matter, and the sea itself appeared as an uncivilised, untamed wilderness, Roman law was able to provide practical solutions to deal with real-life sea problems. Thus, I would propose to look at Rome as both defined and confined by the sea, but ultimately overcoming not just the physical but also the legal challenges presented by the sea.

Emilia Mataix Ferrándiz is Maria Zambrano Fellow in the Law Faculty at the University of the Basque Country and a Research Fellow at the University of Helsinki. She is the author of Shipwrecks, Legal Landscapes and Mediterranean Paradigms: Gone Under Sea (Brill, 2022) and co-editor of Roman Law and Maritime Commerce (Edinburgh, 2022).

Want To Learn More?

The Afterlife of Ships in Thonis-Heracleion: Recycling, Abandonment, and Ritual Sacrifice at an Egyptian Port

By Damian Robinson

What happens to a ship at the end of its life? Underwater archaeology at an Egyptian port near Alexandria provides a vivid picture of very different fates. Read More

On the Potential of Deep-Submergence Archaeology

By Shelley Wachsmann

Ancient mariners sailed open waters and quite a few ships sank. Now thanks to new technologies archaeologists can access shipwrecks in even the deepest waters. Read More

The Rise of Silver Coinage in the Ancient Mediterranean

By Gil Davis

Why was money invented? Metals had been mined and exchanged with other commodities for millennia. But the 7th century BCE Greek city-states had a new idea. Read More