Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

October 2022

Vol. 10, No. 10

Carved, Signed, Crossed Out – Documents on Wooden Sticks from Ancient South Arabia

By Peter Stein

Legal contracts carved on palm-leaf stalks, correspondence laid down on cigar-shaped sticks? The mode of writing used in Ancient South Arabia, the legendary realm of the Queen of Sheba, was especially unique. The Sabaeans and their neighbours did not write on common materials such as leather or papyrus but rather on something surprisingly simple: branches of fresh wood just cut off the tree.

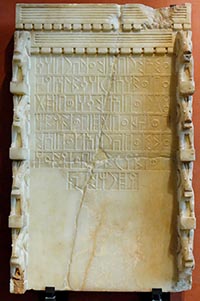

South Arabia, called “Araby the blest” by Greeks and Romans, was famous among the ancients for its wealth. This fame was based on long-distance trade in incense and exotic spices – goods from Eastern Arabia, the Horn of Africa and even India, which were in great demand in the Ancient World. To modern scholarship, however, the South Arabian culture is famous not so much because of incense and myrrh (which played in fact a rather marginal role in the original sources from the region) but because of its extraordinarily rich output in written documentation: thousands of impressive monumental inscriptions, mainly on rock and stone, but also on bronze tablets and other objects. More than 12,000 texts have thus far been discovered – written in four different languages (Sabaic, Minaic, Qatabanic and Hadramitic), spread over the territory of present-day Yemen up to central Saudi-Arabia and covering a time-span of about 1500 years from the early 1st millennium BCE (thus contemporary to the Neo-Assyrian empire) up to the 6th CE (immediately before the rise of Islam).

Irrespective of its peculiar appearance, the Ancient South Arabian script originates in the Canaanite alphabet of the late 2nd millennium BCE. The Sabaeans (the word sabaʾ means “travel” in their language!) probably migrated southwards through the Arabian Peninsula after the political breakdown of the Near East in the 12th century BCE probably – bringing with them the alphabet to Yemen. The script was then adopted by peoples already established in the region – the Minaeans, Qatabanians and Hadramis. These peoples had not made use of previous scripts and spoke Semitic languages differing markedly from Sabaic.

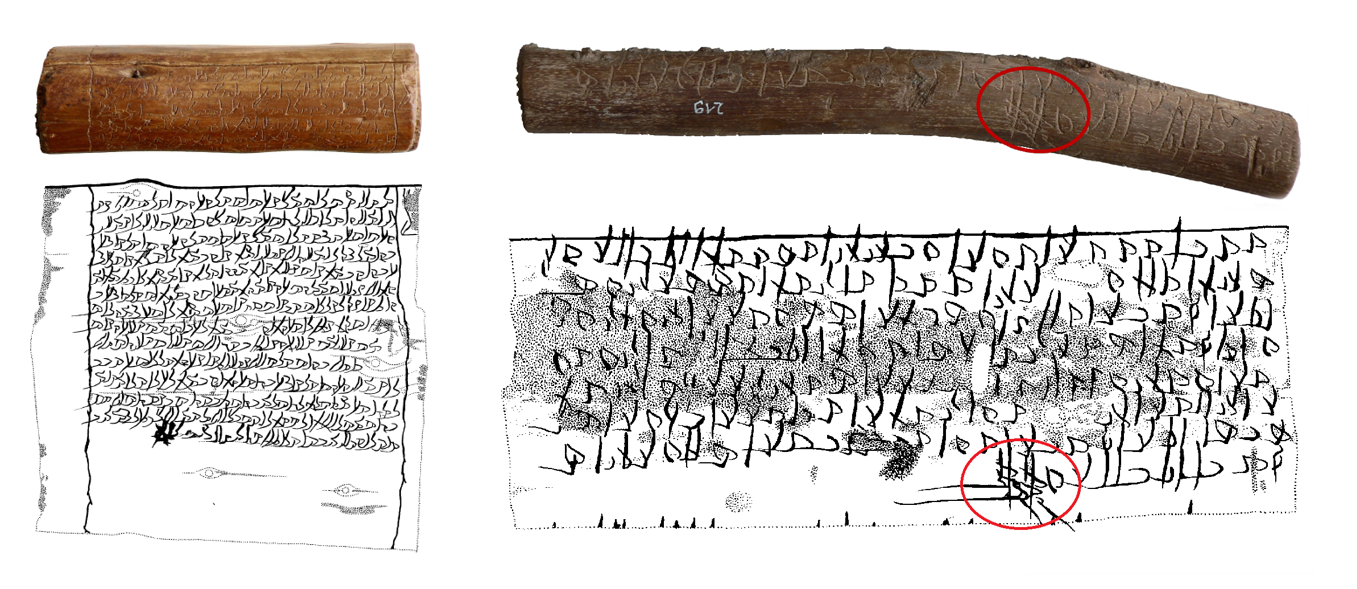

A selection of inscribed wooden sticks from Ancient Yemen, with texts in Sabaic and Minaic languages, from the mid-1st millennium BC (L 014) to the 5th century CE (L 102). Apart from L 102, all pieces are made of palm-leaf stalks (Oosters Instituut foundation, Leiden; photos © W. Vreeburg).

At first glance, this script appears to fit perfectly the needs of monumental epigraphy: bold characters of a distinctly geometric shape pretending to be made just for public display. But astonishingly the script was also used for handwriting in daily life, on documents that are as small as a cigar and made of segments from palm-leaf stalks and branches of other wood – a material that is most cheaply available and easily prepared. In that respect, this material can best be compared to the so-called ostraca, broken pieces of pottery or stone, waste materials that served as writing surfaces in many neighbouring civilisations.

Unlike writing on ostraca, however, the script was not applied on the sticks by pen and ink, but rather incised with a pointed stylos. Thus the mode of manuscript writing does not in fact differ markedly from monumental epigraphy. Nevertheless, an increasing sense for fluent writing led to a gradual alteration of the script in the wooden documents towards a real cursive, characterised by curved, inclined letter forms. After a couple of centuries it had in fact become a script of its own, lacking any similarities with the contemporary ductus of the inscriptions.

Palaeographic chart showing the development of the Ancient South Arabian script in its monumental (left) and cursive forms (right) from the Early (ESab) to the Late Sabaic (LSab) period, i.e. from about the 8th century BC to the 6th c. CE. © Peter Stein

Dependent on the length and diameter of the wooden support, comprehensive documents of any kind could be laid down this way. Correspondence on private and business matters, accounts and contracts about transfer of money and goods, quittances of settled debts, and notes from the ritual practice such as oracular requests and responses are frequent genres among the inscribed sticks.

To make these documents effective, they could even be signed. Many business documents and some letters contain signatures by the involved parties as well as by other persons who witnessed the act. The individually formed signatures often show discernible elements of the particular names. These signatures make clear that the wooden stick was in fact the original document, whereas a monumental inscription that happens to exhibit the same text for public announcement could only be considered a copy.

The invalidated documents were nevertheless kept in the archive for certain reasons. One of these was obviously the need for sample texts in scribal education, since numerous school texts were found mixed with the original deeds, letters, and so on. The place where they were kept was obviously a central office, serving not only for any kind of correspondence by the local population but also transmitting the skills of writing from one generation to the next. Every larger settlement in Ancient Yemen must have had such an office, though not even a handful have been discovered thus far. The bulk of the inscribed wooden sticks known so far stem from one single spot: the ancient city of Nashshān, today as-Sawdāʾ, in the wadi al-Jawf in the north of the country, were they survived beneath the soil to be rediscovered by local tribesmen as late as in the 1970s.

Left Image: A legal deed in Sabaic language stating that two twin daughters were handed over into the ownership of their mother’s family, who were servants to the father of the two (X.BSB 61 = Mon.script.sab. 1, about 3rd century CE; Bavarian State Library, Munich; images © P. Stein). Right Image: Sabaic letter of the 5th century CE. The text closes with the words “the one of the clan Gadanum (i.e., the sender) has signed”, followed by the individual signature of that person (X.BSB 155 = Mon.script.sab. 219; Bavarian State Library, Munich; images © P. Stein).

Eventually a legal matter was settled, or a debt was paid. Once a legally binding document became invalid, it was also visibly obliterated by breaking it to pieces (an easy procedure with a small piece of wood!) or by crossing out the written text. These techniques of “splintering” or “scratching,” which are even alluded to by specific terms in monumental inscriptions, have long been misunderstood – until the first examples of such annulled documents came to light.

The invalidated documents were nevertheless kept in the archive for certain reasons. One of these was obviously the need for sample texts in scribal education, since numerous school texts were found mixed with the original deeds, letters, and so on. The place where they were kept was obviously a central office, serving not only for any kind of correspondence by the local population but also transmitting the skills of writing from one generation to the next. Every larger settlement in Ancient Yemen must have had such an office, though not even a handful have been discovered thus far. The bulk of the inscribed wooden sticks known so far stem from one single spot: the ancient city of Nashshān, today as-Sawdāʾ, in the wadi al-Jawf in the north of the country, were they survived beneath the soil to be rediscovered by local tribesmen as late as in the 1970s.

Peter Stein is Professor of Semitics at Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena.

For Further Reading:

Multhoff, Anne: “Und es sei aufgelöst und aufgehoben”. Zur Annullierung juristischer Urkunden im vorislamischen Südarabien. In: Françoise Briquel Chatonnet, Catherine Fauveaud & Iwona Gajda (eds.), Entre Carthage et l’Arabie heureuse. Melanges offerts à François Bron (Orient & Méditerranée 12), Paris 2013, pp. 105–118

Stein, Peter, Semitic Documents on Wooden Sticks: Manuscript Writing in Pre-Islamic South Arabia. In: Andreas Kaplony & Daniel Potthast (eds.), From Qom to Barcelona. Aramaic, South Arabian, Coptic, Arabic and Judeo-Arabic Documents (Islamic History and Civilization 178), Leiden & Boston 2021, pp. 24–54

Stein, Peter & Rijziger, Sarah: The South Arabian zabūr Inscriptions from Maqwala, near Ṣanʿāʾ, Yemen. In: George Hatke & Ronald Ruzicka (eds.), South Arabian Long-Distance Trade in Antiquity – “Out of Arabia”, Newcastle upon Tyne 2021, pp. 310–351

Want To Learn More?

The Alphabet: The First Thousand Years

By Aaron Koller

The alphabet is probably the most important information technology ever invented. But why did it take a millennium to spread unevenly around the ancient Near East? Read More

Monumental Sandstone Reliefs from the Neolithic: New Insights from the Camel Site in Saudi Arabia

By Maria Guagnin, Guillaume Charloux, and Abdullah M. AlSharekh

Camels in Saudi Arabia are not unusual. But life-sized carvings of camels dating to the Neolithic points to an era when the peninsula was green and rock art flourished. Read More