Not a Friend of ASOR yet? Sign up here to receive ANE Today in your inbox weekly!

April 2022

Vol. 10, No. 4

The Concept of Music in Ancient Mesopotamia

By Daniel Sánchez Muñoz

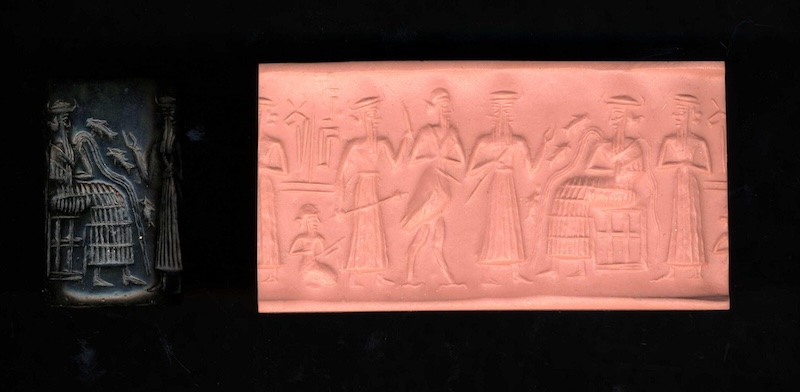

Cuneiform texts, more or less well-preserved real musical instruments, and iconography inform us about the instruments, performers, and compositions in Mesopotamian musical practice. But what do we know about the Mesopotamians’ thoughts on their music?

Musical treatises such as the Chinese Yuè Jì (2nd–1st centuries BCE) are still lacking for Mesopotamia. A “Mesopotamian concept of music” may be reconstructed to some extent, however, by paying attention, among others, to literary texts, especially those written in Sumerian between the 22nd–18th centuries BCE, but mostly preserved in copies dating to the 18th century BCE, in Early Old Babylonian times.

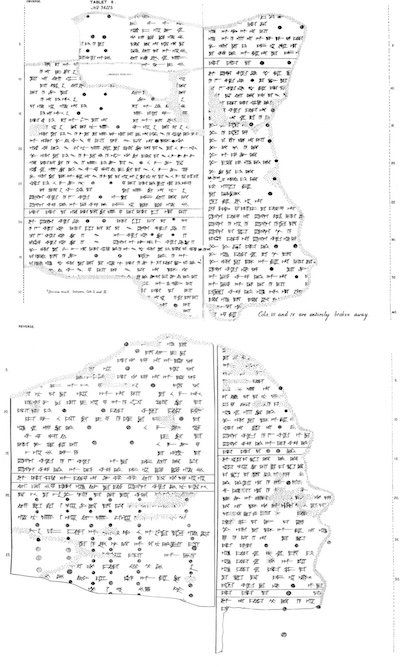

Among those Sumerian literary texts, two excerpts from Sulgi B (lines 154-174) and Išmē-Dagān A+V (lines 367-377), merit the closest attention. In both excerpts, Kings Sulgi of Ur (ca. 2092–2045 BCE) and Išmē-Dagān of Isin (ca. 1953–1935 BCE) boast about their musical abilities, thus presenting themselves as ideal rulers who were experts on everything.

The way they describe their musical expertise is very informative about how music could be conceptually understood, at least, in Old Babylonian Mesopotamia. This is especially true when the ideas expressed in both hymns are paralleled by other Mesopotamian texts. Thus, the inclusion of music among the disciplines to be mastered by an ideal ruler might be compared to the scenario in the mythological narration Inana and Enki. There, music and ability on multiple instruments (e.g. the ĝeš-gu3-di, perhaps a lyre) are listed among the “fundamentals of civilization” (me in Sumerian).

Let us focus, then, on how music in Mesopotamia was conceptually organized according to these two hymns. At the beginning (Sulgi B: 154–156; Išmē-Dagān A+V: 367), both rulers state that they have devoted themselves to music. Though simple, such a statement is already very rich in describing the Mesopotamian concept of music.

On the one hand, the action of devoting oneself to music is described with the expressions gu2 … šum2 (lit. “to give the totality [of oneself] to something”) (Sulgi B: 154) and a2 … šum2 (lit. “to give the strength [of oneself] to something”) (Išmē-Dagān A+V: 367), which seems to describe music as something that could require enormous physical (and mental) dedication. This idea finds a parallel in another Old Babylonian Sumerian dialogue: The Father and His Wayward Son (lines 107–112). Here, a father says to his son that no other “craft” (gašam) was as difficult as the “scribal office” (nam-dub-sar), suggesting, thus, the prestige of scribes. The difficulty is referred to by the term ge17(-g)(lit. “painful”), which would suggest that the scribal profession was so hard that it could sicken its devotees. But the son prefers instead to devote himself to a “painful” office like that of the musician (nam-nar), whose full understanding was out of reach for many people. It is the age-old story of a father who wants his child to be successful, while the child wants to pursue his/her dreams.

On the other hand, Kings Sulgi and Išmē-Dagān are devoted to something called nam-nar in the Sumerian text. Technically, such a word might not refer to “music” per se, but just to the “office of the nar”, where nar (base of nam-nar) refers to a musician who performs at a variety of ceremonial events (e.g., banquets, feasts, processions, or the praise of kings and deities).

Under the rubric of nam-nar, a different kind of music is also included, however: the laments, that is, compositions belonging to the domain of the gala/kalû(m) “lamentation priest”. For instance, in Sulgi B, 173–174, the king claims to be familiar with the šumun-ša4 and i-ši-iš laments. In line 173, Sulgi also claims to play the ge-di, a double-pipe that has its musician the lu2 ge-di-da (lit. “person of the ge-di”).

The ge-di was used for “urban” events, such as accompanying some laments during the liturgy. But the same type of instrument (if more rudimentary) could also be played by shepherds for a sort of “folk music,” as was the case for other instruments. All this suggests that, although Mesopotamians knew different musical styles (“ceremonial”, “elegiac”, and “folk” music) for different situations, those styles did not constitute separate worlds, but they could be encompassed under a global category (nam-nar, suggested here to have multiple meanings, such as “music” and “musician’s office”).

This is also the case in societies following the European musical tradition, where “music” encompasses different styles (pop, rock, jazz, classical, etc.) and the same instrument, such as the flute, may be used in élite and popular styles (such as orchestral music, the Irish folk tradition or the progressive rock of Jethro Tull). Mesopotamian society has also been perceived as unable to formulate abstract concepts such as “music”. This mindset on Mesopotamian thought has recently started to change, however.

The above-exposed might appear to contradict the usual understanding of two Sumero-Akkadian terms that seem to describe different musical styles or genres. The first term is the Akkadian nigûtu(m), sometimes translated as “joyful music.” This is an abstract form of nagû(m), which is equated in a commentary with ḫadû(m) “to rejoice.” Sound phenomena encompassed by nigûtu(m) would thus be spontaneous ones, issued from general rejoicing and probably not seen as music per se in Mesopotamia (even if non-Mesopotamian people might feel it as “music”). It might be compared with expressions in other languages, such as the German einen Freudentanz aufführen, which metaphorically refers to a dance caused by uncontainable happiness.

The second term is nam-gala/kalûtu(m). This word refers to the above-mentioned gala/kalû(m), usually understood as a singer of laments when he was a priest with some musical duties. The musical instruments and “chanting” involved in the performance of the prayers and laments by the gala/kalû(m) were just instruments for making them more expressive. This recalls the situation, among others, of the Qur’ānic “chant,” which is excluded from al-mūsīqā (“music”) in the Arabic world. One might even wonder, then, to what extent the “sound” activities of gala/kalû(m) were considered, or not, as “music” by the Mesopotamians, much as, for instance, in European Medieval times, when the pipe organ was seen not so much as a “musical instrument” per se but an extension of the human voice and thus allowed in churches.

Returning to Sulgi B and Išmē-Dagān, after the statement about the kings’ dedication to the music, the texts present what each ruler considered to be the most important aspect of this discipline. Sulgi refers to his knowledge “inside and out” (buru3 daĝal-be2, lit. “in their depth and width”) of the tigi2 and a-da-ab praise hymns, defined as “perfect musical genres.” (nam-nar šu du7-a). But a common idea emerges from both excerpts: Singing was the most important of the musical “instruments.”

This preeminence of singing over (other) instruments in Mesopotamian music is paralleled elsewhere. Thus, Sumerian proverbs usually state that good musicians did not have to master many songs —just one, really—but to perform them with a pleasant voice (za-pa-aĝ2 du10-g) and with different vocal techniques (e.g. ad ša4 “tremolo”) correctly. Moreover, in the dispute between Enki-ḫeĝal and Enki-talu, one student suggests that his colleague will be never able to master the “music” (nam-nar) because he was not able to use his “tongue” (eme) and “mouth” (ka) correctly for performing different songs.

(Model) legal texts from different periods also emphasize this preeminence. In an Old Babylonian model contract, the student Ḫedu-Eridu chiefly learns how to sing the tigix and a-da-ab hymns. Even much later, an Akkadian legal text from the reign of Cambyses II (ca. 529–522 BCE) still emphasizes this idea, as a person called Nabī-Enlil should mainly learn the zimru-songs during his musical training.

The rest of Sulgi B and Išmē-Dagān A+V mostly refers to the instruments both kings were able to master. The exact identification of some of these is still debated, but they seem to refer mostly to stringed instruments (e.g., the ĝešsa-eš lute). This is probably related to the previous comments about singing: The most important musical instruments in Mesopotamia would be those accompanying the singer during the performance.

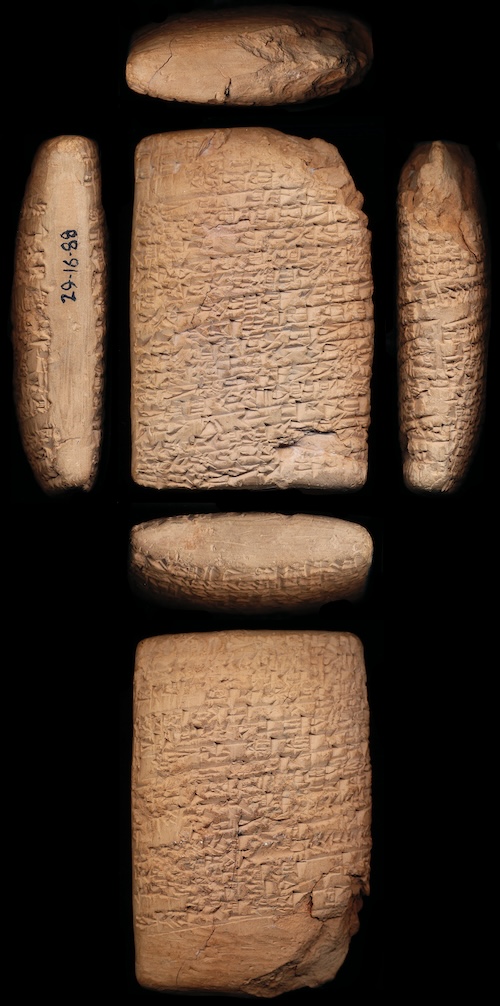

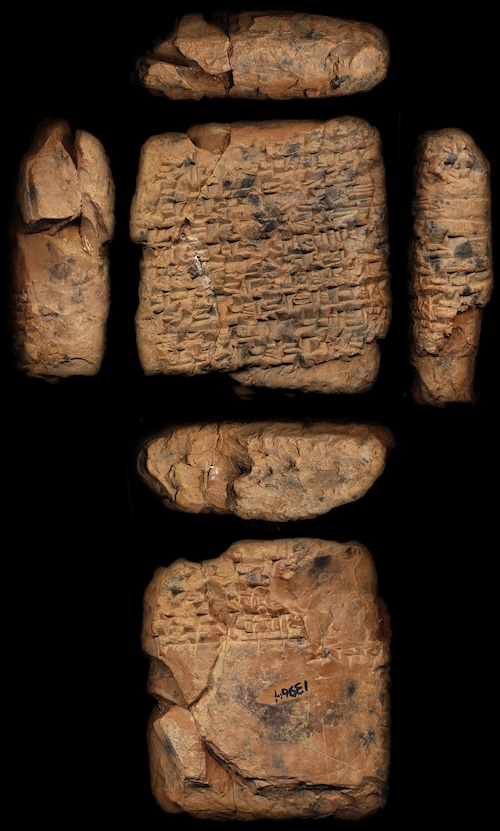

A detail from Sulgi B still requires attention: Lines 158–160 refer to how Sulgi had designed rules for the ascending (zi-zi-i) and descending intervals (šu2-šu2) for the ĝeššu-kara2 lute. Also, in Sulgi B, the king alludes to his knowledge of the “good tuning” (kam-ma sa6-ga) of the ĝešgu2-uš and za3-mi2 chordophones. Sources for studying the music theory system in Mesopotamia such as an Old Babylonian tablet from Ur dealing with the tuning cycle of the za3-mi2/sammû harp are still scarce and dispersed in terms of chronology, typology, and provenance. Excerpts like this from Sulgi B suggest, however, that music theory was a real concern for musicians in Mesopotamia, even if those concerns were not usually written down.

We have considered apparent constants in the Mesopotamian concept of music, but other aspects changed over time, for instance, to the interconnections of music with other disciplines/activities. Thus, in the late third millennium BCE, administrative documents suggest that musicians were connected with “bear tamers” (u4-da-tuš) and “snake charmers” (muš-laḫ5). Female musicians also had connections with weavers, probably because singing helped to alleviate the hard work of weaving, as happens even today. But none of these associations remained by the first millennium BCE; far from it, musicians at that time were closely connected with, among others, incantation priests (āšipū). Thus, according to a Seleucid tablet, part of the so-called Compendium of incantations, a sakkikû incantation is said to be part of the “musician’s repertoire” (nam-nar). That is, a musician (not necessarily an incantation priest) could recite such an incantation.

Although by no means exhaustive, these examples show how ancient Mesopotamian music constitutes an interesting chapter in the history of human conceptions of what is music and musicality, and how this art fits into the overarching culture.

Daniel Sánchez Muñoz serves as “Margarita Salas” Postdoctoral Fellow (Hebrew University of Jerusalem & Universidad de Granada).

Want To Learn More?

Music in Ancient Mesopotamia

By Uri Gabbay

We have a wealth of sources from ancient Mesopotamia: archeological, iconographical, and, most significantly, textual. Hundreds of thousands of cuneiform tablets in collections around the world shed light on the everyday life, economy, law, literature, and religion of ancient Mesopotamia. Read More

Prehistoric soundscapes. Mill-songs and the music of work in Ancient Mediterranean and the Near East

Prehistoric soundscapes. Mill-songs and the music of work in Ancient Mediterranean and the Near East

By Luca Bombardieri

Milling grain was hard work in antiquity, but what did it sound like? Ancient art and sculpture give us an idea, as does modern evidence. Read More

The Earliest Music in Ancient Egypt

The Earliest Music in Ancient Egypt

By Heidi Köpp-Junk

Music is a human universal. Already by the middle of the 3rd millennium BCE a great number of Egyptian texts and images referred to music and musicians, and attest to a complex hierarchy of musicians. But the beginnings of Egyptian music are much earlier. Read More