May 2021

Vol. 9, No. 5

Monotheism or Monopoly? Akhenaten and His Religious-Political Reform

By Jiří Janák

Few personalities of the ancient world excite as much interest for scholars, artists, religious believers and general public as Akhenaten, the Egyptian ruler who carried out a fundamental reform of religion and political ideology in the mid-14th century BCE. He introduced and supported the cult of the sun disc (called the Aten) as the only god venerated by the king and his royal family.

Was the king an enlightened religious leader and an idealistic politician, or was he a mentally ill and physically frail person? Should we see in him the predecessor of Moses, Thales or Jesus, or should we label him as a dictator and the first sectarian? Although archaeological, material, textual and pictorial data do not reveal much about the inner motivation of Akhenaten (who began his reign under the name of Amenhotep IV), we may analyse them in the light of his actions.

It must, however, be pointed out that many of the iconic motifs of the so-called Amarna reform (called after the modern name of Akhenaten’s residential city of Akhetaten) had been present in Egyptian religion and ideology long before the ascent of Amenhotep IV to the throne. This even applies to the use of the word aten (sun-disc) in Egyptian cult, to the concept of the singularity or uniqueness of one god, to the substantial union between the sun god and the sovereign, and to the king’s symbolic function as a mediator between human beings and deities. The main difference of Akhenaten’s reform was a radical and untraditional notion of exclusivity. Nevertheless, we can still gain new insight into Akhenaten’s motivations by analysing theological, cultic and iconographic changes within his religious-political reform.

One god, one city, one ruler

Before Amarna, there were two dissimilar, yet interconnected planes in ancient Egyptian religion. The first was represented by the locally specific cults of individual towns or administrative regions, the other by the nation-wide pantheon dominated by cults of several major centres (mainly Memphis, Heliopolis and Thebes) closely tied to royal ideology. Local cults were usually bound to a single deity, a town god with whom other deities were connected in relevant constellations, such as triads of major political centres (e.g., Amun, Mut and Khonsu of Thebes) who were recognized throughout Egypt during the New Kingdom. Still, some local deities may have been truly site-specific and limited to a single region or place, not known or mentioned in other parts of the Egypt. Thus, Egyptian gods often appeared as the gods of towns, and the towns used to represent places of their earthly abodes.

Within the national pantheon, these local deities retained some of their domestic roles, bonds and statuses but they also yielded to the authority of the state-recognised king of gods, gained new roles and formed new constellations with gods of different cities. Political authorities of the state could not ignore the importance of the region and the allegiance of every person to his or her town, nor was it possible to leave out the original, town-specific characteristics of any of gods in the state plane of religion. Hence, just as the Egyptian state represented the Two Lands composed of individual regions, ancient Egyptian religion was rather a federalized system than a homogenous unity.

Although the number of officially acknowledged gods supported by the palace was reduced to one during Akhenaten’s reform, the texts of the Amarna period reveal that (like all the locally based gods of the Egyptian pantheon before Amarna) both the Aten and his cult were closely connected with a city. Akhenaten’s new administrative and residential town of Akhetaten (modern Tell el-Amarna) did not only represent a royal seat, but it mainly was considered the seat of the god Aten himself. It was built in a pure place solely for the sun god whose close bonds to this cultic centre are also reflected in his epithets. The new residence thus represented the god’s dwelling place, sacred territory or a temple-like settlement rather than a city in the traditional sense. From the symbolic point of view, it seemed as if the whole Egyptian state dominated by the order of maat (royally maintained cosmic balance) had materialised in a single city.

Besides being the sun god’s representative (or rather representation), here the king became the true life-provider of the people. Akhenaten was well aware of the traditional notion of god–town inseparability. This implies that the withholding of official support from the majority of gods and their local cults, which resulted in the flattening of the federalized system of the pantheon, represented the means to suppress the autonomy of local authorities –both divine and human.

By restricting the number of officially recognized and supported gods to a single entity endowed with universal authority, the Egyptian religion and ideology would form a fully centralized state. Moreover, the reform also allowed Akhenaten to absorb a great deal of influence that was formerly ascribed to powerful dead, the so-called akhu. These mighty spirits of the blessed dead had traditionally functioned as intermediaries between the common people and the world of the divine. It was not by chance that Amenhotep IV chose the name of Akhenaten to deliver the main ideological message about his religious reform. As Akh-en-Aten (i.e., the akh of Aten), the ruler was the exclusive intermediary of the exclusive god.

Regardless of whether the reform was motivated by political needs or not, it resulted in centralisation of authority, which allowed the king to gain control over spheres of power previously dominated by town-gods and their priests, local administrative authorities and high officials. Thus, although it cannot be proved that Akhenaten – with his vision of a single god dwelling in a single city – tried to eliminate the power of local administrative and religious centres, absolute centralisation of power in one place, in the hands of one person and tied to one divine cult was exactly what he achieved. At least for a very limited period of time.

Far from People’s Hearts

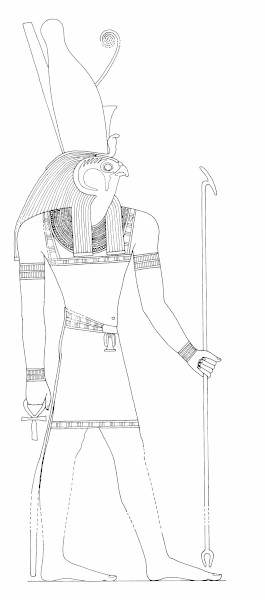

Besides their roles and cultic constellations within the pantheon, Egyptian gods were characterised by their names and iconographic forms. These two aspects made the essence of the hidden divine beings comprehendible. The traditional Egyptian way of depicting divine beings oscillated between zoomorphic and anthropomorphic representation, but frequently the two were joined into a combination of a human body and an animal head.

Solar deities Ra and Horus, for example, were often depicted as men with the head of a falcon. One of the reasons for matching an animal to a deity was to point out characteristic features and functions of the respective entity, which in the real world would manifest themselves in the appearance, behaviour and symbolic meaning of a certain animal. Such natural associations could present the basis for emphasising various aspects of a specific manifestation of the divine. However, the Egyptians did not consider this manner of representation of deities to be a depiction of their accurate images or their real shapes. The iconographic images of the gods represented “composite hieroglyphs”, whose purpose was not to capture the real image of the entity in question, but rather to describe the nature of this entity and make it understandable. The human relationship to the world of Egyptian gods was not so much a matter of faith as of knowing and cognition.

A comparison between the traditional style of representing Egyptian deities and the form used to depict the one god during the Amarna period reveals another important aspect of the Aten reform. Like other creator gods before him, the Aten was considered to be the supreme creator and ruler of everything on earth, but his cult bore also features taken from the royal cult, evident from his name and titles, or from hymns and prayers addressed to him.

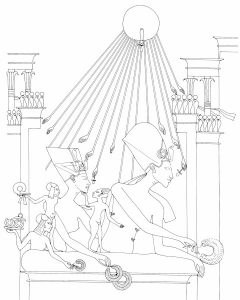

In the oldest attestations of the cult introduced by Akhenaten (still as Amenhotep IV), which survived in the temple complex of Karnak in Thebes, the god Aten appears in a more traditional form. Like Ra, Horus or Harakhty, he is shown as a man with a falcon’s head adorned by a sun disc and uraeus (solar cobra). Later, this traditional form disappears and makes space for a new iconographical feature: the Aten then starts to be represented purely as a sun disc with the uraeus and many rays. The rays of the disc have human hands at their ends and with those hands the Aten reaches to offerings and to the king and his family, whom he presents the sign of life (ankh).

Unlike the images of deities with animal heads, human bodies and various attributes, the new manner of depicting the Aten did not offer a detailed testimony about the god’s essence, traits, characteristics, functions and about his mythological background. Nor were the images of the Aten equipped with captions referring to his speech. This mute image of the light emanating from the sun disc was the same as anyone could see in nature. The Aten was the life-giving sun.

Images of religious or cultic motifs, as well as scenes of everyday life appear in Amarna art without mythological references and thus seem to depict only the real world perceivable by the senses and observed with the eyes, as if Akhenaten took the symbolic literally. Hence, one may interpret the so-called realism of the Amarna art as an artistic tool for diminishing the symbolic and hiding the sacred. Only the natural world illuminated by the life-giving sun and experienced by senses was available to the people: they could see the Aten. But the king, as the only son of the Aten, has been entrusted with much more: he knew his divine father and the mysterious ways of the sun. The Aten even resided in the king’s heart when the sun set below the horizon.

Even the all-embracing cosmic authority and power of the god must be understood in political context of the king’s earthly power and authority. The hymns thus make sure to assert this concept in their concluding statements: the all-powerful Aten who resides far away in celestial heights had created all the cosmos for his only son, the king Akhenaten. The sun god of the Amarna reform was visible daily in the sky, he brought everything to life and looked down on his creation, but he also lived too far from the world and its inhabitants. The Aten rested in a close, exclusive relationship with his son, who was the sole person who had placed the god into his heart and who knew his hidden ways. This theological concept was (again) very well mirrored in iconography. Aten’s rays reached exclusively to his son and to his royal/divine family.

In Amarna, the sun became a god who might be far way, but whose rays still reached the ground; a god people could look at, yet no one could know; a creator, who creates himself, yet craftsmen do not know him. In spite of all his visibility and theological simplicity, the Aten was a god uncomprehended to all with the exception of his only son Akhenaten. And, in this theological paradox, the Aten (the Sun Disc) has become more hidden than Amun (the Hidden One).

Jiří Janák is director of the Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University, Prague.

All photos and drawings: © archives of the Czech Institute of Egyptology, Charles University, Prague.

For further reading:

Jiří Janák, “Akhenaten: Monotheism or Monopoly?” in M. Bárta, M. Kovář (eds.), Civilisations: Collapse and Regeneration Addressing the Nature of Change and Transformation in History, Academia: Prague 2019, pp. 187–212.

Want To Learn More?

The Making of Monotheism

By Michael Hundley

The Hittites made due with a pantheon of at least 3000 gods. So how did belief in a single god develop? Yahweh rose to prominence from relative obscurity, but the trail had already been blazed by Marduk and Assur. Read More

Nefertiti on Her Chariot – The Female Use of Chariots in Ancient Egypt

Nefertiti on Her Chariot – The Female Use of Chariots in Ancient Egypt

By Heidi Köpp-Junk

Chariots appear in Egypt in the early second millennium as modes of transportation and weapons of war. For a brief time, women were also drivers. Read More