April 2018

Vol. 6, No. 4

Getting Old in Ancient Egypt

By Grigorios I. Kontopoulos

The Lifespan of the Ancient Egyptians

Old age was a situation that included only a very small portion of the Egyptian population. The study of the anthropological evidence from several cemeteries as well as the census declarations from Roman Egypt defined the average life expectancy for males at 22.5-25 years and for females at 35-37 years. Under these considerations, an individual in his mid-thirties was considered an old person in ancient Egypt.

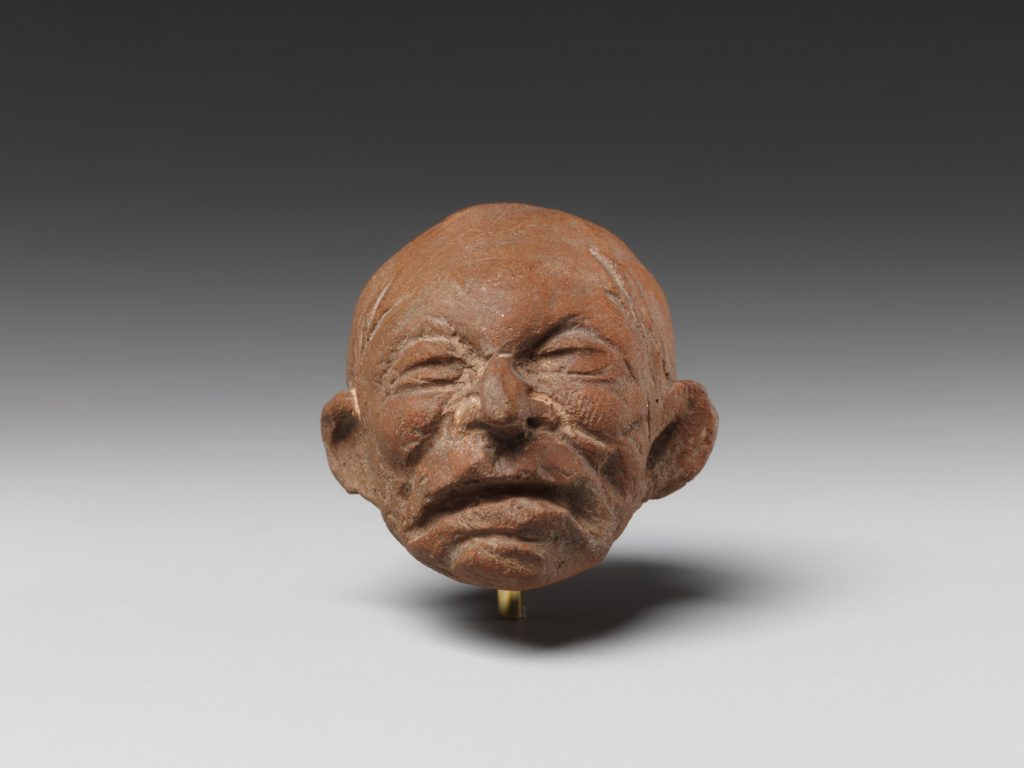

Head of a statue of an older man, ca. 2550–2460 BCE (The Met Museum)

The Ideal Lifetime

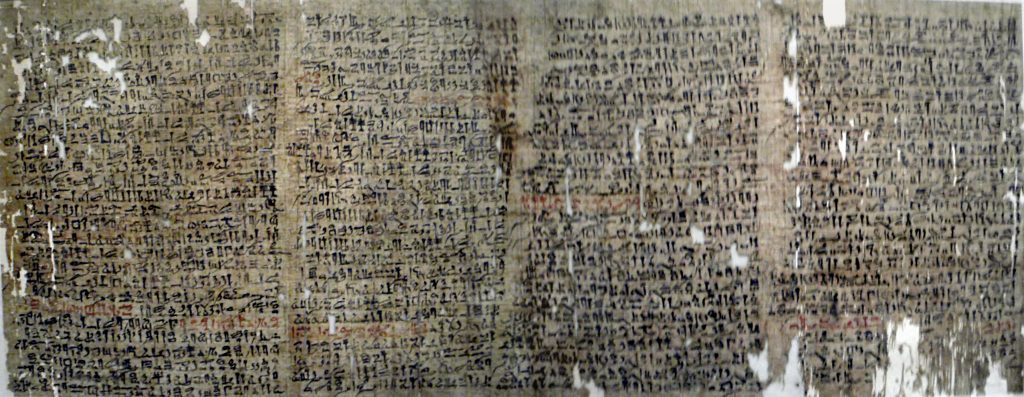

Although the evidence suggests a quite low life expectancy, there were exceptions of individuals who reached substantial old age. These fortunate ones were usually members of the Egyptian elite. Several cases of individuals who reached – or who wished to reach – a long lifespan were attested in ancient Egyptian literature. Although the majority of texts reflected the experiences of the literate male elite, several examples dated during the Dynastic period (such as the famous Papyrus Westcar from the Middle Kingdom, ca. 2000 BCE) indicate that 110 years seemed to be the ideal lifespan.

Papyrus Westcar (Wikimedia Commons)

Perceptions of the Older Generation

While the perception of who is old is certainly changeable, today due to the constant rise of our standard of living, ‘old age’ is a stage in human life that declared by the symptoms of aging. The ancient Egyptian perception for the process of aging was not very different than the picture we have today. In texts from the Dynastic period, a pessimistic picture of the process was given:

In texts from the Dynastic period, a pessimistic picture of the process was given:

“O king, my Lord! Age is here, old age arrived, Feebleness came, weakness grows, [childlike] one sleeps all day. Eyes are dim, ears deaf, strength is waning through weariness (Instructions of Ptahotep).

“Would that my body were young again! For old age has come; feebleness has overtaken me. My eyes are heavy, my arms weak; my legs fail to follow. The heart is weary; death is near” (The Story of Sinuhe).

Head of an old man, ca. 200-1 BCE (The Met Museum)

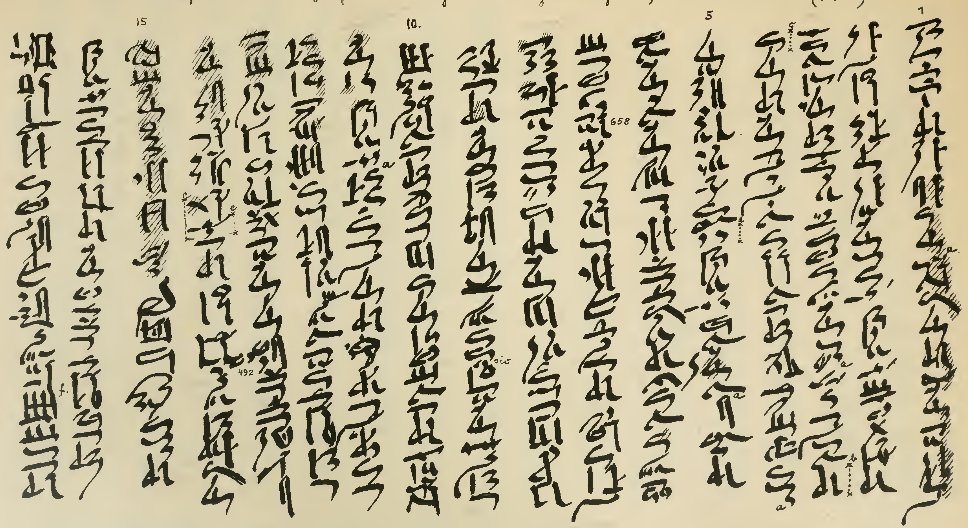

Portion of Sinuhe (Wikimedia Commons)

But pessimism regarding physical decline was not the only description of the aged individuals. In the story of the “Three Tales of Wonder” from Papyrus Westcar, Prince Hardedef describes the magician Djedi as someone who:

“Is of a 110 years, who eats hundred loaves of bread, half an ox for meat and drinks one hundred jugs of beer to this very date.”

As the story continues, the young Prince greets the magician, and his words strongly contrast with the descriptions of old age given in other texts:

“Your condition is like that of one who lives above age-for old age is the time of death, enwrapping, and burial- one who sleeps till daytime, free of illness, without a hacking cough.”

On the one hand being old perceived as the last stage of life, as a time of agony and misery, but on the other hand it could be perceived as a watershed between adolescence and maturity, especially for the wealthier portions of population. Differences in social strata defined the way that the elderly was regarded.

The Care for the Elderly

The textual evidence regarding care for the elderly in ancient Egypt makes it becomes obvious that this was a matter for the family, especially for the lower and middle classes of society. Various census lists from Kahun and Deir-el-Medina suggested that the elderly, especially women, remained significant participants in their domestic group until death. Apart from being members of their children’s households, the elderly also received a regular stipend from their offspring, as an ostracon from the working class village of Deir el-Medina revealed:

“And I gave to him emmer amounting to 2 ½ sacks as rations every month from year 1 until year 2, second month of the inundation season to third month of the summer season, making 10 months, each 2 ½ sacks. Total 27 ½ sacks.”

In the same spirit, one of the four documents related to the property of Lady Naunakhte records an agreement between Khaemnun and his son Kenherkhepeshef:

“After the workman Khenherkhepeshef said, ‘I will give him 2 ¾ sacks’, and while he will swear an oath of the Lord, saying, ‘As Amon endures, as the ruler endures, if I take away this grain ration of my father, my reward (the washing bowl) shall be taken away.’

The agreement reveals another aspect of the relationship between parents and children, the enforcement of the care for the elderly through inheritance. The inheritance was used to ensure children would look after their elderly parents. The will of Naunakhte is representative:

“But see, I am grown old, and see, they are not looking after me in my turn. Whoever of them has aided me, to him I will give (of) my property, (but) he who has not given to me, to him I will not give of my property.”

Although care for the elderly inside the family context seemed to be the only solution for the lower and middle classes of the Egyptian society, the situation was quite different for the elderly members of the Egyptian elite. The elderly who belonged in the upper class were allowed to keep their titles and their official income until the end of their lifetime. This is demonstrated in the institution of the “staff of old age” in documents such as the Instructions of Ptahotep, autobiographies such as that of Amenemhat, or the text that describes the installation of the vizier Weser-Amun. From these it becomes prominent that the “staff of old age” was an assistant to officials who belonged to the highest levels of the Egyptian administration. That duty was usually given by Pharaoh to one of the sons of the official. Under the appointment of his son, the father remained financially independent and at the same time the succession of the son was guaranteed.

Senwosret III (ca. 1874 – 1855 BCE) (Civilization.org)

Apart from the institution of the “staff of old age”, elderly members of the Egyptian elite had extra sources of income to secure their financial independency after retirement. Founding a statue cult through a donation to a temple allowed officials to drawn a supplementary income after retirement. By donating property, including slaves, to a royal statue, a citizen, with the King’s permission, could found a cult and become its prophet. With this appointment as a prophet, he could then receive a share of the cult income, untaxed and protected from state demands.

Similarly, the donation of an individual’s property to a temple allowed him to receive an annual income from the harvest. By donating his property to a temple, the individual secured protection from state demands and avoided family disagreements. The inscriptions from the tomb of the Theban scribe Sanmut describe that practice:

“I give all my property together with all my acquisitions to Mut, into the temple of Mut, The Great Mistress of Ishru. Behold, I am establishing it as a stipend from my old age because of my contract.

The Egyptian approach to old age is thus closer to our own than we might have expected. The poor and the middle class took in their elderly and struggled, while the wealthiest schemed to avoid taxes.

Grigorios I. Kontopoulos is a Ph.D. candidate in Egyptology at the University of the Aegean.

For further reading

Rosalind & J.J. Janssen, Getting old in ancient Egypt (London, The Rubicon Press, 1996)

Stol & S. Vleeming, The care of the elderly in the ancient Near East (Leiden, Brill, 1998)

A.G. McDowell, Village life in ancient Egypt: Laundry lists and love songs (Oxford , Oxford University Press, 1999)