Table of Contents for Bulletin of ASOR 391 (May 2024)

Pp. 1-23: “Conspicuous Construction: New Light on Funerary Monuments in Rural Early Roman Judea from Horvat Midras,” by Gregg E. Gardner and Orit Peleg-Barkat

This paper discusses the growing trend in Late Hellenistic- and Early Roman-era Judea (ca. 200 b.c.e.–70 c.e.) for constructing “display tombs”—funerary architecture designed to achieve maximum visibility and project the status of the individual or family who financed the construction, not just in the cities, but also in the countryside. It uses the case study of the recently excavated pyramidal tomb marker at Horvat Midras (Israel), an affluent village, located on the border of Idumea and Judea about 30 km southwest of Jerusalem in the Judean Foothills. After a detailed discussion of the new finds, it is placed within the material and broader socioeconomic contexts of rural Judea in these periods. As will be shown, this monument’s architectural style, location, and other attributes enhance our understanding of monumental funerary architecture in rural settings, adds new archaeological data to often-overlooked rural areas, and contributes to a better understanding of socioeconomic elites in rural Judea at this time.

Pp. 25-45: “A Study of a Unique Roman Funerary Monument and Its Population at Dara in Upper Mesopotamia: A Collective Rock Burial ‘Tower,'” by Charlotte Labedan-Kodas, Ayse Acar, and Nihat Erdoğan

This article provides an in-depth study of a singular funerary monument located in the ancient city of Dara (southeastern Turkey). Its features relate to various influences, some of them outside the Roman world, and present a unique insight into the ritual practices of the inhabitants of Dara. This paper brings together archaeological and taphonomic evidence provided by recent excavations to offer perspectives for the dating of the building and the identification of the people buried there.

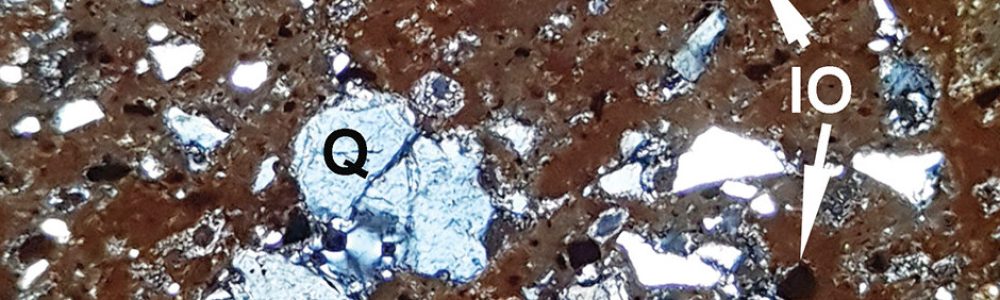

Pp. 47-75: “Domestic Waste as a Window into Crusader-Period Le Lyon (Kibbutz Megiddo/Lajjun, Israel): Insights from a Household Midden and Its Ceramic Assemblage,” by Edna J. Stern, Anastasia Shapiro, Matthew J. Adams, Nimrod Marom, Inbar Ktalav, and Yotam Tepper

The 2017 salvage excavation conducted at the site of Lajjun within Kibbutz Megiddo, Israel, revealed layers of refuse, primarily ceramics, constituting a household midden with finds indicating a 12th-century date and a Frankish cultural affinity. The midden can be associated with the occupation of the ancient settlement of Lajjun by Frankish settlers intermittently in the 12th and 13th centuries c.e., representing a first archaeological window into the Frankish activity at the site and complementing the historical data on the village known from Crusader sources as Le Lyon (Lajjun).

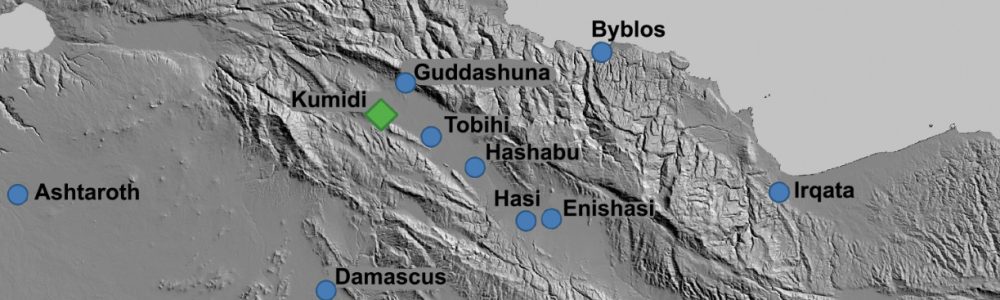

Pp. 77-92: “The Proximity Principle and the Egyptian Levant in the Late 18th Dynasty,” by Francesco Ignazio De Magistris

It has been known for decades that the Egyptians of the 18th Dynasty took direct control of a number of centers across the Levant, that each center was governed by an Egyptian commissioner, and that every commissioner interacted with the rulers of the local city-states. However, the precise number of Egyptian centers and their respective areas of control remains debated to this day. This article revisits these issues by analyzing the relationships between centers, commissioners, and rulers as they appear within the Amarna corpus, with a focus on the proposed proximity principle. This principle posits that Levantine rulers would have primarily engaged with the closest Egyptian center and the closest Egyptian commissioner, rather than a farther one. Through this analysis, the article aims to shed new light on the number of the Egyptian centers in the Levant and the extent of land that they controlled.

Pp. 93-106: “The Future of the Temple of Bel in Palmyra after Its Destruction,” by Maamoun Abdulkarim and Jacques Seigne

This article explores the significance of the Temple of Bel in the history of Palmyra, highlighting key aspects of its design and development. It reviews the measures taken by the archaeological authorities during the French Mandate (1920–1946) to manage and conserve the monument, such as relocating the local community outside the archaeological site far from the sanctuary and the implementation of repairs to the cella. Finally, it discusses the damage wrought by ISIS in 2015 to Palmyra, which included the partial destruction of the temple using explosives, and revisits the work of the specialists who examined this structure after it was destroyed. In order to preserve Palmyra’s cultural legacy, the relevance of the cella’s future conservation needs as a priority are underscored, not simply for the World Heritage Site, but within the wider context of Syria and the region.

Pp. 107-133: “Solving the Starry Symbols of Sargon II,” by Martin Worthington

The city of Khorsabad (ancient Dūr-Šarrukīn), the newly built capital of Sargon II of Assyria, contained multiple instances of a sequence of five images or symbols (lion, bird, bull, tree, plow) which also appeared shortened to three (lion, tree, plow). What did they mean? There is currently no consensus. This paper proposes a new solution, suggesting that the images a) symbolize specific constellations and b) represent Babylonian/Assyrian words whose sounds “spell out” Sargon’s name (this works for both the long and the short version). Combining these two traits, the effect of the symbols was to assert that Sargon’s name was written in the heavens, for all eternity, and also to associate him with the gods Anu and Enlil, to whom the constellations in question were linked. It is further suggested that Sargon’s name was elsewhere symbolized by a lion passant (pacing lion), through a bilingual pun.

Pp. 135-161: “Tel Dor in the Middle Bronze Age and Maritime Adaptation along the Carmel Coast,” by Assaf Yasur-Landau, Chandler Houghtalin, Marko Runjajić, Zachary Dunseth, and Ruth Shahack-Gross

A newly excavated, well-built, Middle Bronze (MB) II–III coastal structure at Tel Dor provides a fresh glimpse into the turbulent settlement history of the Carmel Coast in the first half of the 2nd millennium b.c.e. The structure, incorporating a massive ashlar orthostat, was built in the MB I–II transition or MB II and existed for more than a century before its collapse during the MB III. A tight cluster of radiocarbon data indicates its destruction ca. 1600–1550 b.c.e. As the first Middle Bronze Age structure extensively excavated at Dor, it fills a lacuna in the site’s history. Other Middle Bronze Age finds enable a reconstruction of Dor’s anchorages and create a narrative of settlement patterns on the Carmel Coast, tightly connected with contemporary maritime activities, and reflecting a resilient settlement system devoid of urban centers.

ASOR Members with online access: log into ASOR’s Online Portal here. Once logged in, click the JOURNALS tab in the top navigation bar. Tutorials for how to log in to the Online Portal as well as how to navigate to the Portal Journals page can be found here.

Pp. 163-189: “Reconstructing the Urban Fabric of Nea Paphos by Comparison with Regularly Planned Mediterranean Cities, Using 3D Procedural Modeling and Spatial Analysis,” by Anna Kubicka-Sowińska, Łukasz Miszk, Paulina Zachar, Anna Fijałkowska, Wojciech Ostrowski, Jakub Modrzewski, and Ewdoksia Papuci-Władyka

Nea Paphos, the Hellenistic-Roman capital of Cyprus, was established according to a regular Hippodamian street grid in the Hellenistic period. The city has been subjected to continuous archaeological research since the 1960s. Despite this, the possibilities for reconstructing its fabric were severely limited. This paper aims to gain a more in-depth understanding of the ways in which computational methods can be used in the analysis of ancient urban planning and the reconstruction of its elements, using the similarity of urban processes and social behavior in ancient Greek cities as its main premise. Therefore, a study based on Network and Space Syntax analysis was conducted for cities with a well-recognized urban layout of the Late Classical and Hellenistic periods, namely Olynthus and Priene, and other, less archaeologically explored harbor towns of the Hellenistic period, such as Piraeus and Ptolemais. The results of these studies were then extrapolated to hypothetical reconstructions of Nea Paphos in the Hellenistic period, mainly to propose the location of the main public buildings and to model the urban traffic. This methodology is experimental in its nature. The aim of this paper is to try to assess to what extent the adopted workflow can be useful in reconstructing the landscape of ancient cities.

ASOR Members with online access: log into ASOR’s Online Portal here. Once logged in, click the JOURNALS tab in the top navigation bar. Tutorials for how to log in to the Online Portal as well as how to navigate to the Portal Journals page can be found here.

Pp. 191–225: “The Early Dynastic ‘Maison des Fruits’ at Tell K in Tello (Ĝirsu),” by Christina Tsouparopoulou

Taking as a point of departure a foundation figurine of the 3rd-millennium Early Dynastic Lagashite ruler Ur-Nanše, housed in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens, Greece, this article presents a revised understanding of the “Maison des Fruits” and Tell K at Tello/Ĝirsu. It is centered on the objects and their inscriptions unearthed in and associated with the Maison, includes relevant parallel structures and objects, and concludes with a discussion of the function of the Maison. It is suggested that this was a sacred building closely related to water and fish and leaves open the discussion regarding to whom this structure was dedicated.

ASOR Members with online access: log into ASOR’s Online Portal here. Once logged in, click the JOURNALS tab in the top navigation bar. Tutorials for how to log in to the Online Portal as well as how to navigate to the Portal Journals page can be found here.