2022/2023 Mesopotamian Fellowship Report: Preliminary Report on the Tepe Gawra Lower Town Survey

Khaled Abu Jayyab, University of Toronto

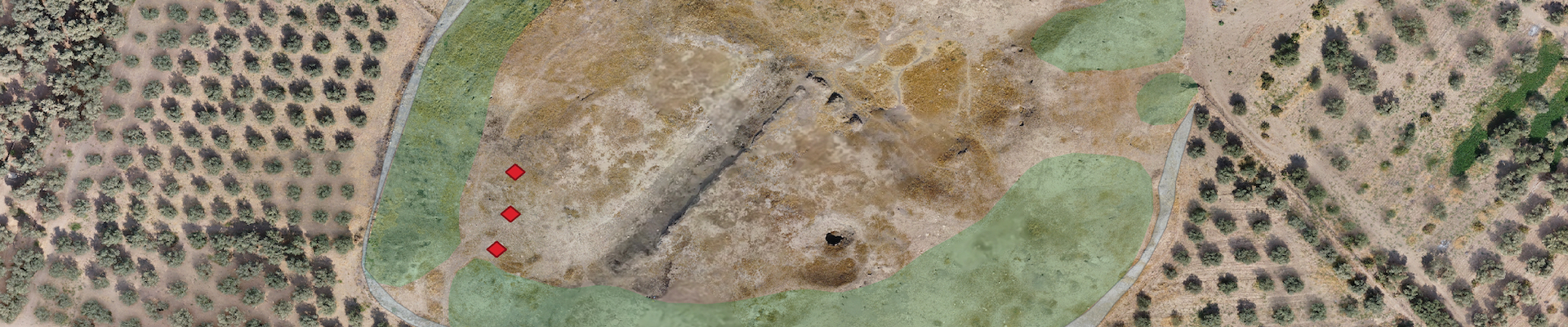

Based on the kind letter of support by the General Directorate of the State Board of Antiquities and Heritage (SBAH), Baghdad, we began the systematic survey of the lower town of Tepe Gawra (344197.14 m E, 4040351.85 m N) in the Ninawa Governate (fig.1) on the 9th of October 2022. Fieldwork at the site was concluded on the 20th of October 2022, with analysis of the recovered materials carried out in the expedition house in the Muthana neighborhood in Mosul. The work at Tepe Gawra was conducted by a Canadian research team from the University of Toronto in partnership with the SBAH office in Mosul.

Location of Tepe Gawra

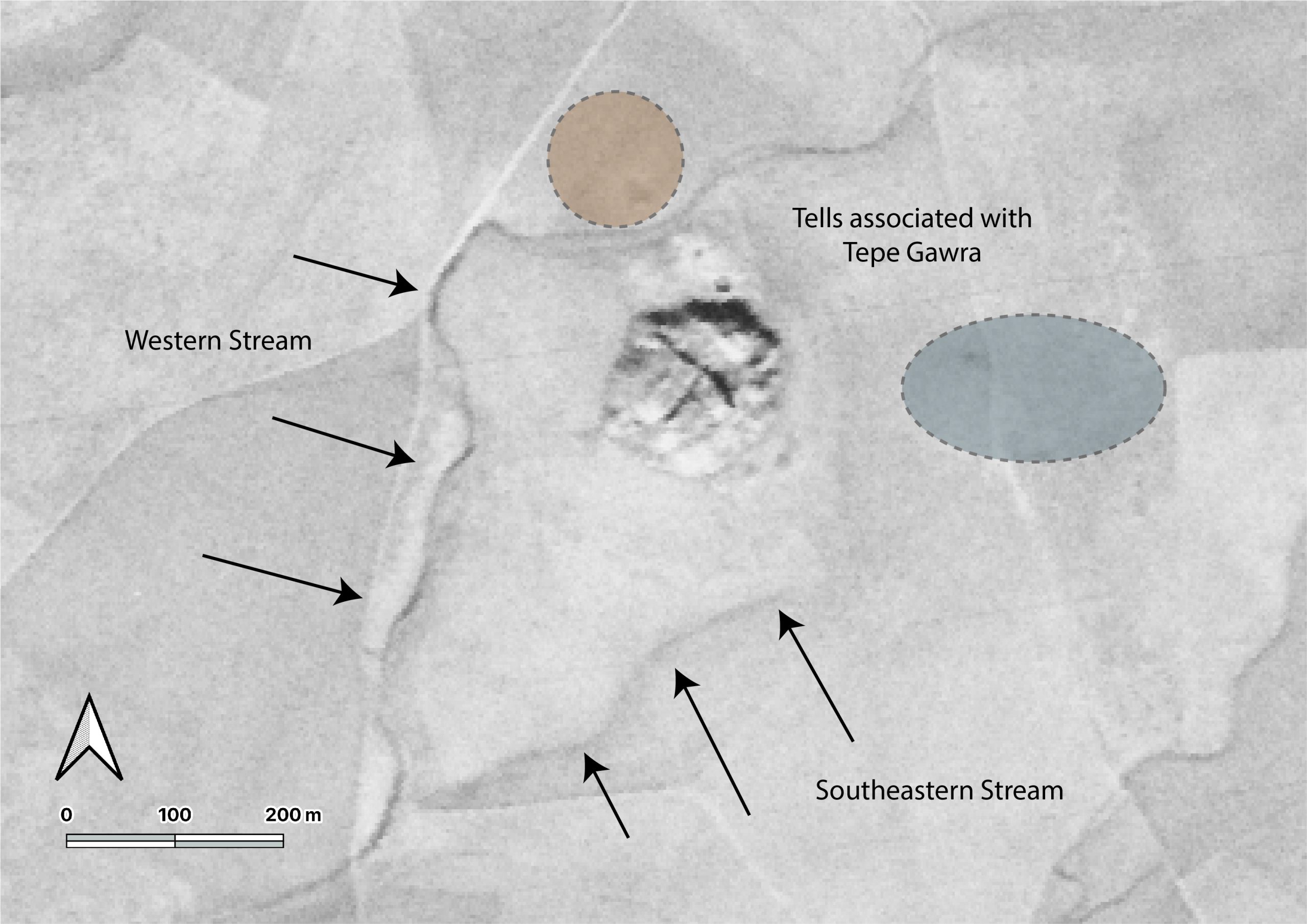

The site of Tepe Gawra is located in the in the Ninawa Plain in the piedmont of the Zagros Mountains. The site is roughly a kilometer and a half to the south of the town of Fadiliyah, and about the same distance from the ancient Assyrian city of Dur Šarukin (Khorsabad) to its east. Tepe Gawra is located in a well-watered plain with several spring fed streams running through the site or near it. This condition encouraged settlement across time resulting in a long sequence of occupation at the site. Today most of the springs that were near Fadiliyah are dry as a result of tapping into the water table with deep wells and pumps.

History of Work at the site and its Significance

Tepe Gawra has long been seen as an essential site for late prehistoric and early historic periods, not only in Iraq but for the region in its entirety. Despite the significance of Tepe Gawra, there hasn’t been work carried out at the site since the 1930’s. The work conducted at the site by Speiser (1935) and Tobler (1950) has revealed a long occupational sequence dating from the Halaf period to the mid second millennium BC. The sequence has very few short-lived gaps in occupation and as such has become a chronological anchor for the region, especially for late prehistory (Halaf, Ubaid, and Uruk/LC). Analytical work carried out by Abu al-Soof (1974), and more recently, Rothman (2002), has expanded our understanding of the Northern Uruk period and has been key to developing the modern Late Chalcolithic (LC1-LC5) chronological scheme (Rothman ed. 2001; Schwartz 2001).

Despite its small size (roughly 2-3 ha. at its base extent), Tepe Gawra has been the hallmark site for the development of complexity during the Ubaid and Late Chalcolithic periods in the ancient Near East. Excavations at the site revealed a local development of a sophisticated infrastructure manifest in construction of temples, monumental architecture, and elaborate administrative practices. The site throughout its occupation shows an involvement in far flung networks connecting it with Highland Anatolia and the Zagros mountains, with connections as far afield as Afghanistan. These connections were seen in the high concentration of objects made of exotic materials such as obsidian, lapis lazuli, carnelian, copper, gold, and silver (Rothman 2002: 8), in addition to the presence of imported utilitarian and luxury ceramics (Abu Jayyab 2019; Rothman and Blackman 2003). The households at Tepe Gawra were also shown to be involved in multiple craft activities such as woodwork, textile production, elaborate administration, stone tool manufacture, and the production of high-end ceramic wares (see Rothman 2002; Rothman and Blackman 2003).

All together the main mound of the site has furnished evidence of highly specialized activities (administration, exchange, and craft production) with very little evidence of agricultural implements and farming practices. This phenomenon is unique as this degree of specialization was only attested at larger contemporary sites that combined specialized activities with extensive farming practices (e.g. Tell Brak reaches over 100 ha during this period). This situation necessitated that the inhabitants of Tepe Gawra relied on an external source for food. Rothman suggested that a functional segregation between sites existed in the piedmont or the foothills during this time (Rothman 2002: 5). He saw that the site of Tepe Gawra was a ‘center’ at the top of a specialized hierarchical network. Within this network Gawra served as an administrative, religious, and craft hub (Rothman 2002: 5-6). In support of the notion of a center, Frangipane argues that the landscape played a role in limiting urbanism in the piedmont around Tepe Gawra where the terrain may have restricted the expansion of agriculture beyond its natural limit restricting the region from producing enough agricultural surpluses to support a large conglomeration (Frangipane 2009: 135).

Research Aims

There is no doubt as to the significance of Tepe Gawra within the region but was the site truly interdependent as part of a large regional network for subsistence? That is, was the site serving a special function that excluded it from food production? There remains a debate as to whether or not there was a lower Chalcolithic period town around Tepe Gawra. Algaze notes (1993: 71-72) – based on personal communication with Gibson – that the mound was surrounded by a lower town. If this was true then the high mound would have been the acropolis of a larger town that still remains systematically unexplored. Rothman did not reject the idea of the presence of a lower town, however he remained skeptical with the absence of empirical data (Rothman 2002: 19).

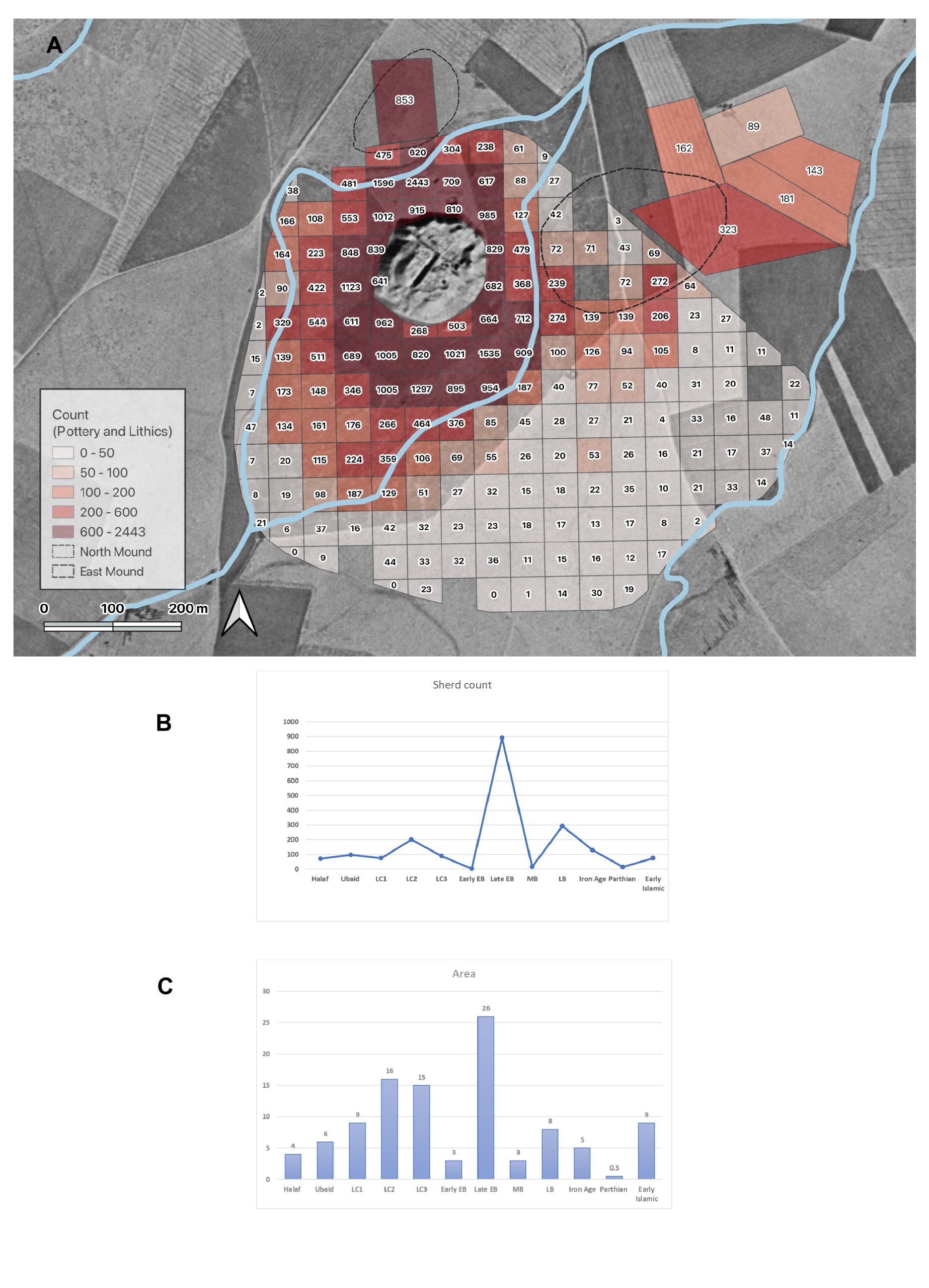

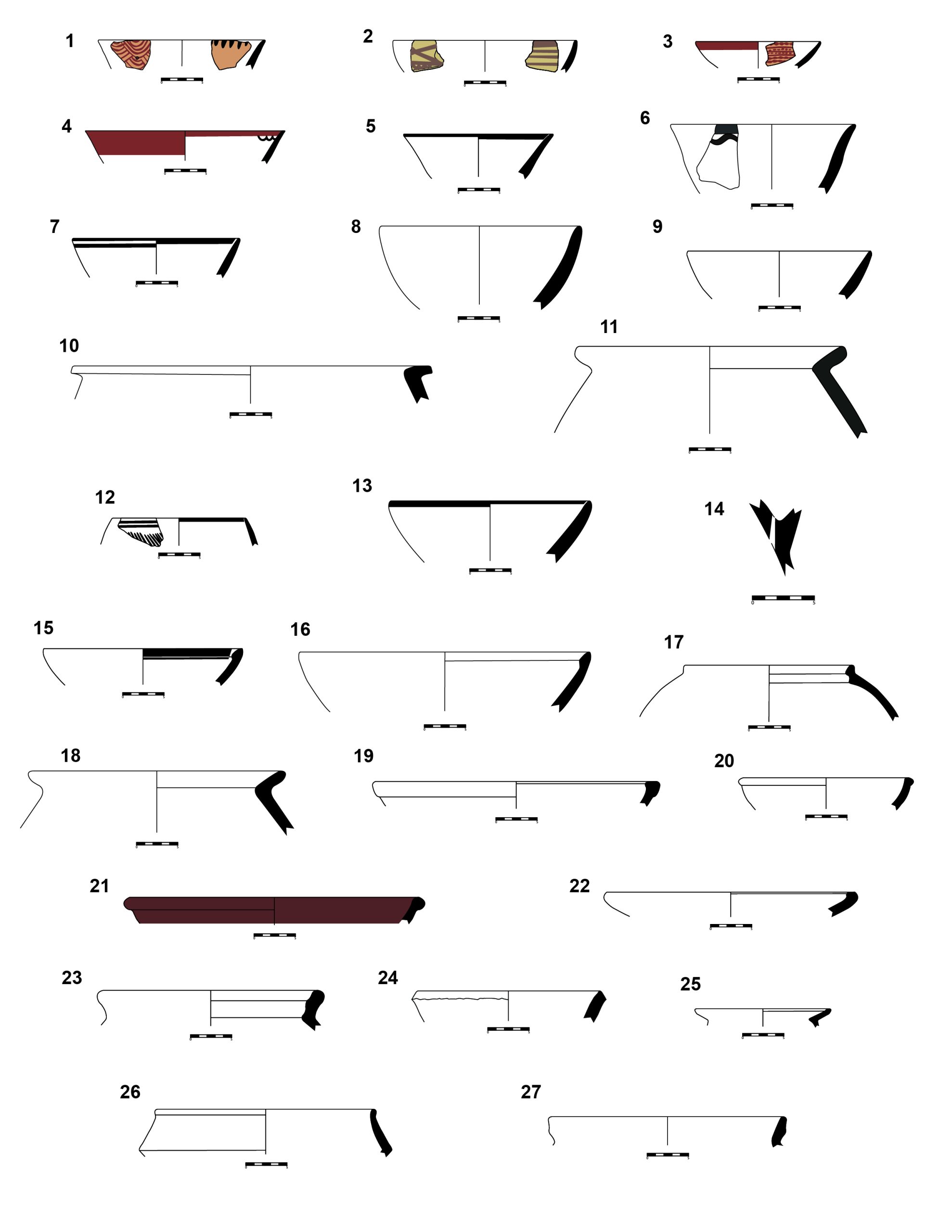

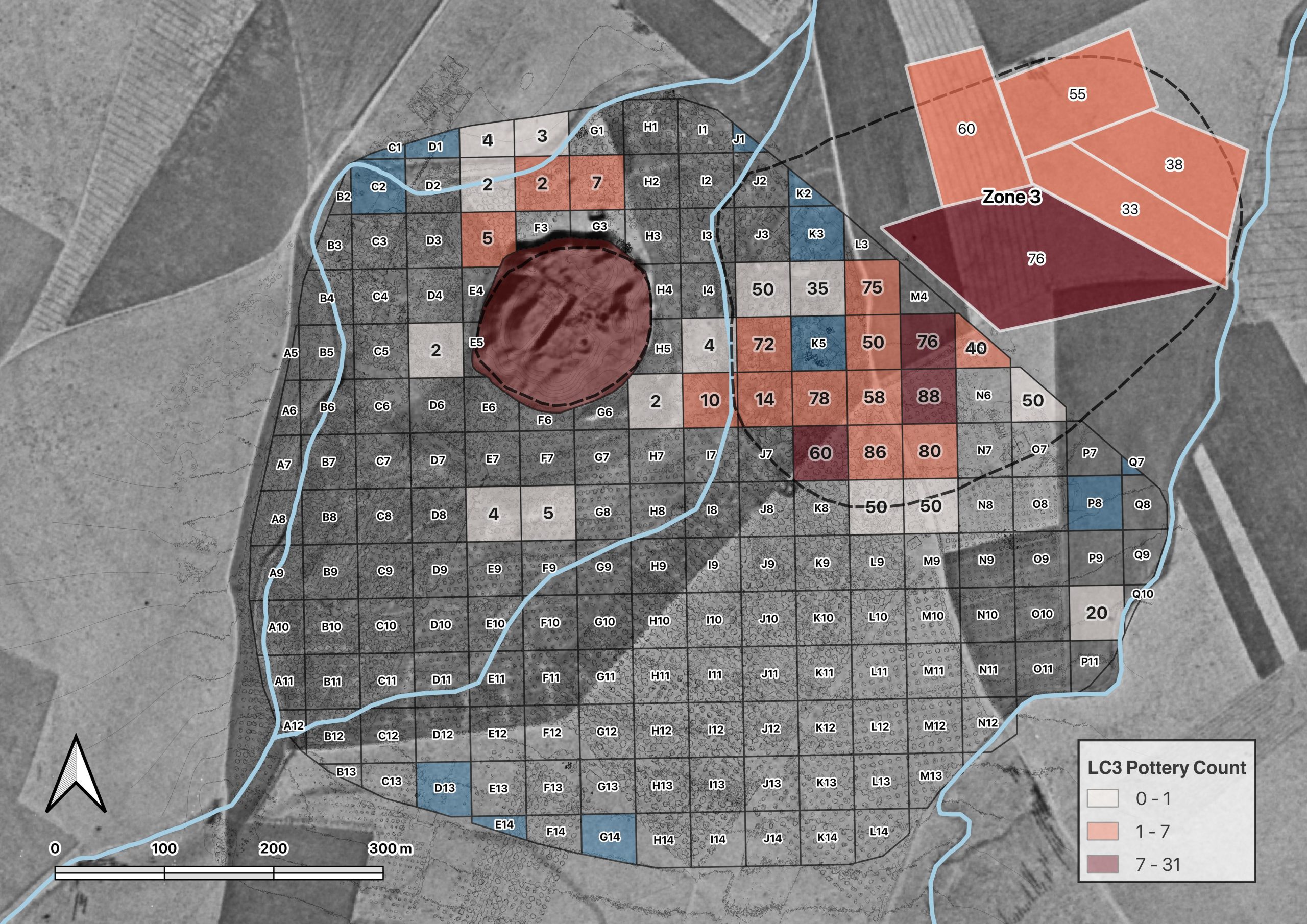

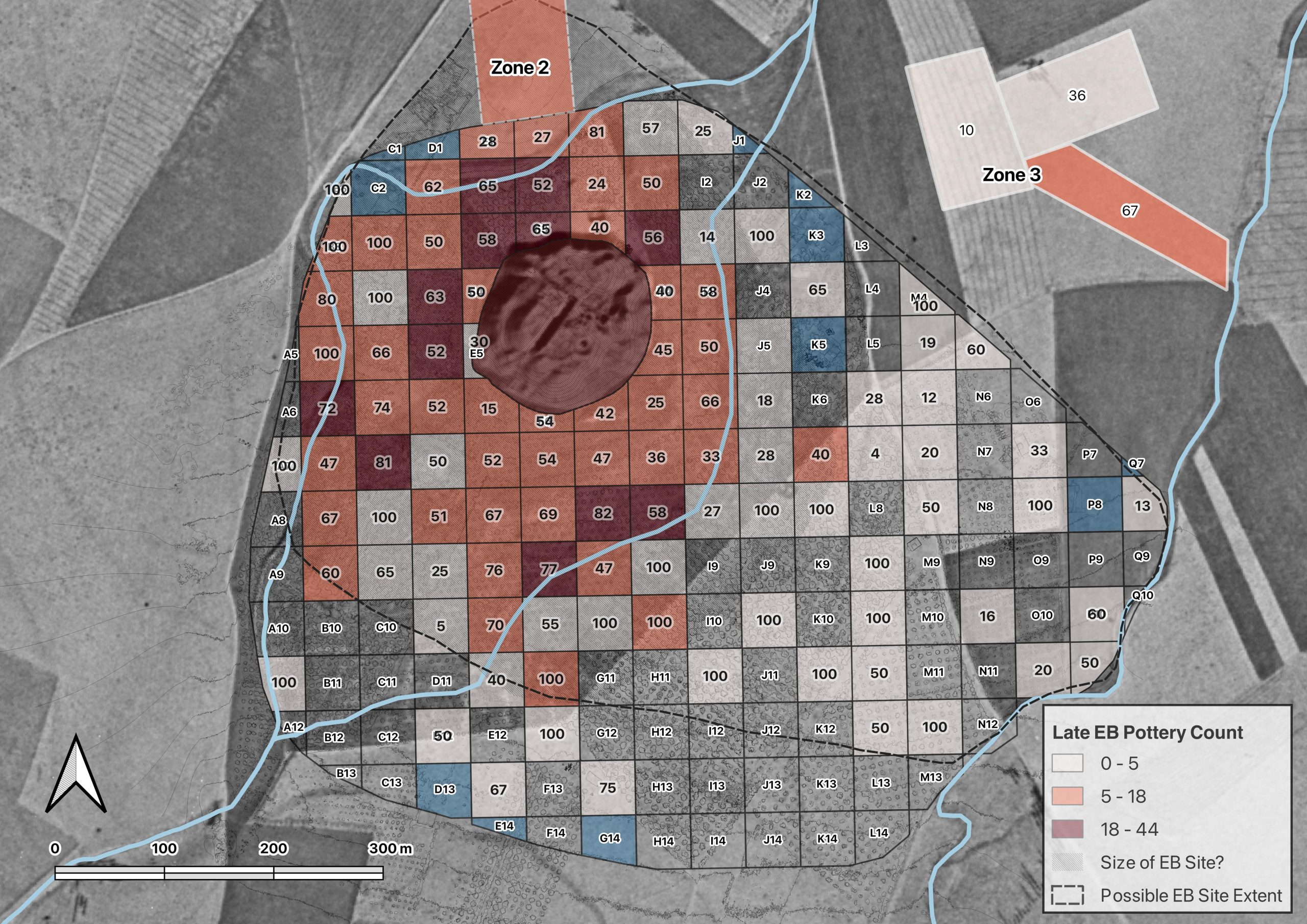

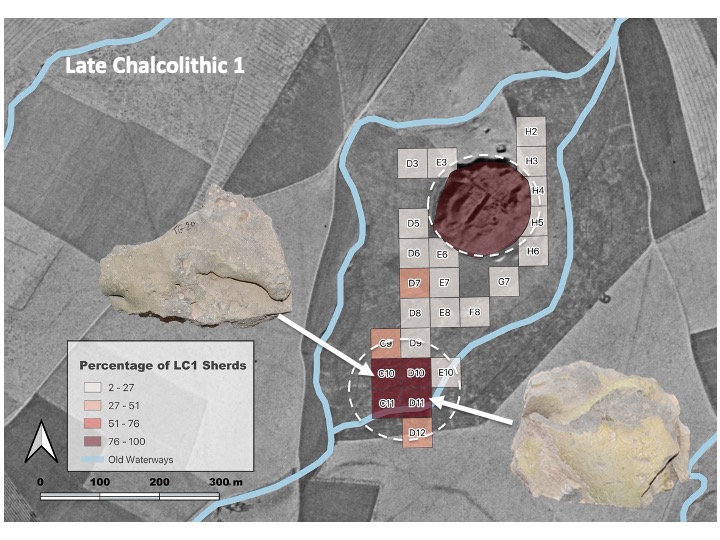

All diagnostic artifacts within the units were collected and taken to the expedition house for processing. Processing consists of washing the artifacts, recording and drawing them, with the aim of carrying out a typo-technological study. The typo-technological analysis entails studying the finds (e.g. ceramic sherds, stone tools) with the aim of identifying the relative age of the artifacts and the technological steps taken to produce them (another avenue that may possibly help us determine periodization). We also analyzed the obsidian stone tools with a portable x-ray florescence analyzer (PXRF). The PXRF will allow us to determine the source/s of obsidian artifacts found at the site and begin to explore new network connections that the site was involved in. The information gathered through the material studies will later be connected to the spatial data through a GIS. Through a period-by-period artifact count from each unit we were able to see the extent of occupation in the area surrounding the tell and detect changes in this occupation from one period to the next.

The most recent damage to the site was caused through its use by members of ISIS. The militant group dug an intricate network of tunnels within the mound (fig.9). These tunnels may impact the integrity of the mound and cause collapses in the near future. Besides the structural issues these tunnels caused, due to their size, the impact on the archaeological remains is equally devastating if not more.

Occupation at the site reached its zenith during the latter part of the 3rd millennium or the Late Early Bronze Age (Akkadian/post Akkadian periods). During this period, we see the largest extent of the site reaching approximately 23 ha., or possibly 36 if we take into consideration units with a low density of sherds (fig.14). The site declines during the Middle Bronze Age, and eventually shifts slightly to the north during the Late Bronze Age and the Iron Age, where the mound of Tepe Gawra itself becomes too narrow at the summit to sustain a village. The Final occupation in the environs of the site occurs during the late Sassanian/Early Islamic period where settlement shifts to the southern edges of the survey zone.

Bibliography

Abu al-Soof, B. (1974). “Prehistoric Pottery from Nineveh, Gawra, and the Neighboring Sites.” Sumer 30: 1-10.

Abu Jayyab, K. (2012). “A Ceramic Chronology from Hamoukar’s Southern Extension.” In Catherine Marro (ed.) “After the Ubaid: Interpreting Change from the Caucuses to Mesopotamia at the Dawn of Urban Civilization (4500-3500 BC).” 87-128. Varia Anatolica XXVII.

Abu Jayyab, K. (2019). “Nomads in Late Chalcolithic Northern Mesopotamia: Mobility and Social Change in the 5th and 4th Millennium BC.” Unpublished PhD. Thesis, University of Toronto.

Algaze, G. (1993). “The Uruk World System: the Dynamics of Expansion of Early Mesopotamian Civilization.” University of Chicago Press.

Al-Quntar, S. & Abu Jayyab, K. (2014). “The Political Economy of the Upper Khabur in the Late Chalcolithic 1-2: Ceramic Mass-production, Standardization and Specialization.” In McMahon, A. & Crawford, H. (eds.) “Preludes to Urbanism: The Late Chalcolithic of Mesopotamia.” 89-108. McDonald Institute Monographs. Cambridge.

Frangipane, M. (2009). “Non-urban Hierarchical Patterns of Territorial and Political Organization in in Northern Regions of Greater Mesopotamia: Tepe Gawra and Arslantepe.” Subartu XXIII: 135-148.

Jotheri, J. (2022). “Reforming (and Decolonizing) Excavations and Survey in Iraq.” ANE Today X: 12.

Rothman, M. ed. (2001). “Uruk Mesopotamia and Its Neighbors: Cross-cultural Interactions in the Era of State Formation.” School of American Research Press.

Rothman, M. (2002). “Tepe Gawra: The Evolution of a Small Prehistoric Center in Northern Iraq.” Philadelphia, University of Pennsylvania, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology Press.

Rothman, M. & Blackman, J. (2003). “Late Fifth and Early Fourth Millennium Exchange Systems in Northern Mesopotamia: Chemical Characterization of Sprig and Impressed Wares.” Al-Rafidan 24: 1-21.

Schwartz, G. (2001). “Syria and the Uruk Expansion.” In Ed. Rothman. M. “Uruk Mesopotamia and Its Neighbors: Cross-cultural Interactions in the Era of State Formation.” 233-264. School of American Research Press.

Speiser, E. (1927). “Preliminary excavations at Tepe Gawra.” Annual of the American Schools of Oriental Research 9: 57-94.

Speiser, E. (1935). “Excavations at Tepe Gawra, I.” Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Tobler, A. J. (1950). “Excavations at Tepe Gawra II.” Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.