You can receive NEA (and other ASOR publications) through an ASOR Membership. Please e-mail the Membership office if you have any questions.

Pp. 252–261: “New Evidence of Two Transitions in the Neolithic Sequence of Northeastern Iran,” by Kourosh Roustaei and Hasan Rezvani

As early as the 1950s the Zagros range in western Iran has been one of the main arenas for seeking the earliest villages and domestication of plants and animals in the eastern wing of the Fertile Crescent. Pioneering works of Robert Braidwood during the 1950s and early 1960s at a number of sites in Iraqi Kurdestan and the central Zagros region of western Iran, such as Karim Shahir, Jarmo, Asiab, Sarab, not only produced the first information on the Neolithic of this region, but also motivated a series of fieldworks targeting the Neolithic period in western Iran during the 1960s–1970s (e.g., Braidwood). Excavations at the early Neolithic sites of Guran, Ganj Darreh, Abdul Hosein, Ali Kosh, and Chogha Sefid during these two decades contributed significantly to a clearer picture of the Neolithic of the Zagros region and suggested this region as one possible center of early domestication in the Near East (e.g., Hole, Flannery, and Neely). Although this status of the Zagros was partly eclipsed because of both a two-decade hiatus in Neolithic research during 1980s–1990s and the concurrent, increasing investigations on the early Neolithic in the Levant and southeastern Anatolia, it seems that the Zagros is regaining its position regarding early domestication and the initial stages of the Neolithic way of life in the Fertile Crescent through the crucial information obtained from recent excavations at some early Holocene sites, such as Chogha Golan and Sheikhi Abad (e.g., Matthews, Matthews, and Homamadifar; Riehl et al.).

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 262–271: “Umm an-Nar Ritual Building in Dahwa 1 (DH1), Northern Al-Batinah, Oman,” by Nasser S. Al-Jahwari and Khaled A. Douglas

The Umm an-Nar Culture was identified after the first scientific archaeological excavations took place in the Oman Peninsula (modern-day Oman and United Arab Emirates) during the late 1950s by the Danish team at the Umm an-Nar Island in Abu-Dhabi (Frifelt 1991, 1995). Since then, several sites have been excavated by different teams in the region, such as Hili (Cleuziou 1980, 1982), Ras al-Jinz (Cleuziou and Tosi 2000), Bat (Thornton, Cable, and Possehl 2016), Meyaser (Weisgerber 1978, 1981), Bisya/Salut (Orchard and Stanger 1999; Orchard and Orchard 2002), Tell Abraq (Potts 1989, 1990, 1991, 2000), and Asimah (Vogt 1994). These excavations have revealed abundant material about the culture of these third-millennium BCE (2700–2000 BCE) communities. The inhabitants of this region had developed an intensive and complex long-distance trade network with societies in Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley (Cleuziou 2003).

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 272–280: “Gender, Deities, and the Public Image of Sobekneferu,” by Kelly-Anne Diamond

Beginning as early as the Twelfth Dynasty, female masculinity was an alternative for Egyptian royal women seeking to legitimize their claim to the throne, communicate their power, and exercise their authority. The Eighteenth Dynasty female king Hatshepsut (ca. 1473–1458 BCE) attracted the most attention for not conforming to traditional western gender norms. However, three hundred years before Hatshepsut, a lesser-known female king—Sobekneferu (ca. 1777–1773 BCE)—embodied power through her performance of masculinity (Halberstam 1998: 1–5). She promoted herself as king of Egypt by assuming a full royal titulary, employing kingly accoutrements, appropriating masculine garb, portraying herself in strong masculine poses, and adopting male prerogatives. Some of Sobekneferu’s preserved imagery illustrates clearly a woman in masculine poses with royal insignia, but her statue in the Louvre (E 27135) shows her with the addition of male dress items (fig. 1; Berman and Letellier 1996: 47; Grajetzki 2006, 63; Callender 1998a: 233–35). With the creation of this statue, Sobekneferu intentionally modified her attire and intensified her expression of female masculinity.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 282–292: “Discovering Early Syrian Magic: New Aramaic Sources for a Long-Lost Art,” by Jessie DeGrado and Madadh Richey

Few magical texts have been recovered from the Levant dating to the first millennium BCE. Three recently published early Aramaic inscriptions help fill this lacuna: an inscribed cosmetic container from Zincirli, a Lamaštu amulet from the same site, and an Aramaic-inscribed Pazuzu statuette. These texts, dated paleographically to the ninth and eighth centuries BCE, afford a window onto local traditions in the Levant and their interactions with Mesopotamian magic. They also provide an impetus for a reanalysis of the infamous Arslan Tash amulets, offering further context for their texts and iconography.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

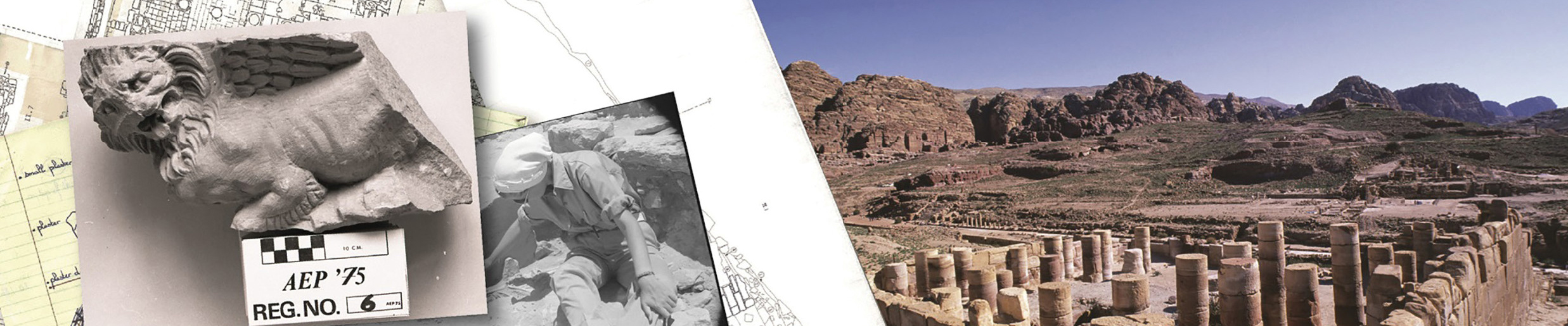

Pp. 293–305: “The Temple of the Winged Lions, Petra: Reassessing a Nabataean Ritual Complex,” by Pauline Piraud-Fournet, John D. M. Green, Noreen Doyle, and Pearce Paul Creasman

The Temple of the Winged Lions (TWL) in Petra is a Nabataean- and Roman-era ritual complex thought to have been founded in the early first century CE (banner photograph and fig. 1). It fell out of use following a major earthquake in 363 CE. This is a contextually rich site for the study of ancient ritual, economy, and society in the Nabataean and Greco-Roman world and part of a larger complex including workshops and domestic spaces. The deity (or deities) once worshiped there remains unknown. The most common suggestion is that the temple was dedicated to Al-‘Uzza, the Arabian divinity whose Greek equivalent was Aphrodite.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 306–315: “A Sasanian Triumphal Arch in Bishapur,” by Alireza Shahmohammadpour

The Sasanian Kingdom (224–651 CE) was the last dynasty before the Muslim-Arab invasion of Iran (Pourshariati 2008: 1–2). Sasanian-era architectural remains—mostly including palaces, castles, temples, bridges, and dams—are scattered throughout ancient Iran. However, the density of monuments in the southwestern regions of the country and in Mesopotamia is higher than anywhere else. Many of the Sasanian buildings excavated and exposed to the elements in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were incorrectly or insufficiently identified by their excavators and have not been subjected to systematic analysis since their initial publication. In the years that have elapsed, erosion and human activity have damaged or erased architectural features that might be useful for understanding Sasanian architecture. One such site is the city of Bishapur in the southwest of Iran. This city was established by Shapur I, the second king of the dynasty, in the middle of the third century and was occupied until the eleventh century, more than four centuries after the fall of the Sasanian Empire (Mehryar 1999: 33). Even at present the surface of the site is covered by apparently random piles of stones, at first glance making recognition of the buildings difficult (fig. 1).

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.