You can receive NEA (and other ASOR publications) through an ASOR Membership. Please e-mail the Membership office if you have any questions.

Pp. 172–181: “An Early Bronze Age Incense Burner from Dahwa (DH1), Northern al-Batinah, Oman,” by Nasser Said Al-Jahwari and Khaled Ahmed Douglas

The Early Bronze Age in the Oman Peninsula is marked by two local cultures: Hafit (ca. 3400–2500 BCE), which is notable for thousands of burials (cairns and beehives) spread over large areas in northern Oman and the lack of settlement remains; and Umm an-Nar (2500–2000 BCE) marked by the first permanent settlements, intensive exploitation of copper, and international trade, mainly with Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley (Potts 1990a: 102–6; 1993: 423–27; Cleuziou 2003; Al-Jahwari 2009, 2013). Five Early Bronze Age sites (DH1, DH5, DH6, DH7, and DH8) have been found in the Dahwa region clustered within an area not longer than 1.7 km. They are distributed on both sides of Wadi al-Sukhun and in the bottom of the wadi itself (Al-Jahwari et al. 2018: 29–30).The location of the sites in the Dahwa region were chosen carefully for several reasons. Primary among these were the water sources: the Dahwa region is located where two major wadis converge. Copper resources were another factor. Also important was the presence of a trade route: Dahwa is a key region connecting the coastal plain to the inland region, such as Hili, Yanqul, and Dhank.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 182–191: “Two Great Households of Old Babylonian Ur,” by Elizabeth Stone, Adelheid Otto, Dominique Charpin, Berthold Einwag, and Paul Zimansky

Visitors to the ruins of Ur venturing into the residential area south of the ziggurat and royal cemetery are confronted with a reconstructed “House of Abraham” (fig. 1), named after the city’s most famous putative resident. It is not clear who decided that this particular structure was the ancestral home of the patriarch, but it was certainly not Sir Leonard Woolley, who closed his celebrated excavations here in 1934. While he was convinced that this city was indeed the Ur of the Chaldees of the Bible—a claim that has not gone unchallenged—and even wrote a book postulating that the Old Babylonian houses here shed light on the origins of Yahwistic religion (Woolley 1936), he doubted that archaeology could ever link Abraham to a specific artifact or building. The massive brick structure one sees today was actually erected only two decades ago to promote tourism in anticipation of a papal visit that was delayed until March 2021. It was built on the ruins of half a dozen individual houses that Woolley had excavated in the area he called AH, generally following their ground plans but connecting the units with doorways to create a single edifice many times larger than any private residence of the early second millennium BCE (fig. 2). If the idea of naming this new creation after Abraham was to promote tourism, it has been a success: Among the thousands who visit Ur every spring, some even come to pray in these rooms, ignoring all warnings that the association with the family of Abraham is suspect.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 192–199: “Grisly Trophies: Severed Hands and the Egyptian Military Reward System,” by Danielle Candelora

All visitors to the massive New Kingdom (ca. 1550–1069 BCE)1 temples in Thebes (modern Luxor; see fig. 1) are bombarded with images of the king smiting foreign enemies, expanding his imperial borders, and overseeing the spoils of war. The texts and reliefs tell us that this booty generally includes livestock, goods, weapons, and prisoners of war, but the grisliest element by far is the enormous mounds of severed hands being piled and counted before the seated king (fig. 2). Eighteenth Dynasty (ca. 1450 BCE) private tomb autobiographies of soldiers indicate that warriors would have presented these trophies as a record of their kills and were rewarded with the so-called gold of valor in a public ceremony (fig. 3).2 Indeed, we even have tomb reliefs and statues of individuals commemorating their receipt of this award. Yet this military custom seems to have appeared fully realized in Egypt during Ahmose’s war with the Hyksos, with few clues as to its origin (Candelora 2019c; Matić 2019: 41–42; Abdalla 2005; Stefanović 2003; Lorton 1974: 57–68). Beyond that, no archaeological evidence of this practice had been found—that is, until 2011 when the excavations at Tell el-Dab‘a uncovered four pits containing the remains of sixteen severed right hands just outside a Hyksos palace.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 200–204: “The Bronze Mouse of Maresha,” by Ian Stern

Maresha was the main city in Idumea during the Hellenistic period. It is located in the Judean lowlands at the intersection of the lateral road from Hebron to Gaza and on the longitudinal road from Beersheba to the Ayalon Plain and then to Jerusalem or Jaffa (fig. 1). The city consisted of an upper city (the tel) and a lower city that surrounded it (fig. 2). Excavations over the past 30 years (Kloner 2003; Stern 2014, 2019) have shown that it was inhabited from the Iron Age through the end of the Hellenistic period with a terminus ante quem dated to ca. 107 BCE.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 206–215: “Pomegranate or Poppy What Lies between the Cornucopias on Hasmonaean Coins?,” by David M. Jacobson and David B. Hendin

The Hasmonaean rulers struck coins, exclusively in bronze, beginning with John Hyrcanus I (135–104 BCE; Hendin 2020). Their most common denomination was a coin with a diameter averaging 15 mm and close to 2 g in weight, which is widely identified with the prutah (PRWṬH) of rabbinic literature (Jacobson 2014: 141). In accordance with a strict interpretation of the Second Commandment, which was then the norm, Hasmonaean coins avoid human images (Hendin 2007–2008: 79–82). In place of a ruler portrait, usually found on east Greek coins of that period, there is a Paleo-Hebrew inscription naming the governing authority, the high priest and governing council (ḤBR), enclosed in an olive wreath alluding to their authority (Hendin 2007–2008: 85–86); see figure 1. The reverse of this coin displays a motif consisting of a splayed pair of cornucopias filled with agricultural produce astride a fruit or seedpod on a straight stalk. Filled cornucopias are commonplace on Hellenistic and Roman coins and their symbolic meaning was understood throughout the classical world as indicating fecundity and well-being. Accordingly, cornucopia motifs are rooted in classical Greek rather than Jewish tradition. Specifically, the cornucopia alludes to the horn of Amaltheia, the she-goat wet nurse of Zeus in Greek mythology, a symbol of prosperity and abundance generally associated with “good fortune” (agathê tychê; Jacobson 2013a: 139). It is worth noting that the coins of the Seleucid king Alexander II Zabinas, featuring a splayed and intertwined pair of filled cornucopias (SC II, nos. 2235, 2237), were struck in 125–122 BCE, at about the time that the comparable Hasmonaean motif made its debut.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 216–229: “Eau de Cleopatra: Mendesian Perfume and Tell Timai,” by Robert J. Littman, Jay Silverstein, Dora Goldsmith, Sean Coughlin, and Hamedy Mashaly

Cleopatra VII, the last of the Ptolemaic rulers of Egypt, reveled in perfume (Plutarch, Life of Marcus Antonius 26.2). She even used it in her seduction of the Roman general Marc Antony. Sailing up the river Cydnus to meet him, she reclined in a canopy spangled with gold, adorned like Venus in a painting. Boys dressed as cupids fanned her and wondrous scents from incense offerings wafted along the riverbanks. Not long after her death in August 30 BCE, a book circulated under her name called Cleopatra’s Cosmetic, full of recipes for fragrant oils and cleansers (Totelin 2017: 114–18).

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 230–237: “A Roman Bronze Bull from the Floor of the Mashhad Pool in Sepphoris in the Galilee,” by Adi Erlich, Tsvika Tsuk, Iosi Bordowicz, and Dror Ben-Yosef

Sepphoris, located in the heart of Lower Galilee, was a main urban center in the Roman period. It is first mentioned by Flavius Josephus (Ant. 13.338) as a Jewish-Hasmonean town, and was later taken over by Herod the Great. During the Great Revolt, Sepphoris eventually took a pro-Roman side and received the name Eirenopolis, city of peace, as appears on its coins (Josephus, J.W. 3.30), and later in the second century it was renamed Diocaesarea (Strange 2015: 22–23). Throughout the Roman period Sepphoris was populated by Jews; it was the home of Jewish sages and of Rabbi Judah, the patriarch who compiled the Mishnah. Alongside the Jewish community of the city there was also a Roman-pagan population, as can be inferred from a Roman temple in the center of the city and a Roman-style mansion with a Dionysiac mosaic on the top of the hill (Weiss 2010, 2015). Furthermore, rabbinic sources attest to a Roman castra inhabited by gentiles in the city (Miller 1984: 31–45). The end of the Roman period in Sepphoris was marked by rapid Christianization of the city, which reached its peak in the fifth century CE; the Roman phase ended with a severe earthquake in 363 that damaged its buildings.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

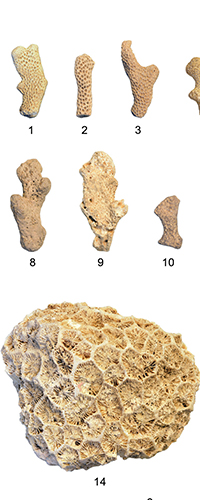

Pp. 238–245: “Corals in the Desert: Recent Discoveries of Red Sea Corals in Byzantine and Early Islamic Sites in the Negev Desert,” by Guy Bar-Oz, Yotam Tepper, and Roee Shafir

Corals have been commercially exploited for many centuries all over the world (Jiménez and Orejas 2017). Traditionally, they have been regarded as mystical objects and hybrid organisms. Their skeletons have commonly been used as remedies and as amulets or jewelry, and they have represented an exotic and valuable resource throughout human history. In the Greco-Roman literature a number of classical authors, such as Aristotle (fourth century BCE, History of Animals 5.16; Ogle 1882) and Pliny (first century CE), referred to the natural history of corals and classified them as enigmatic creatures. Since corals are animals that lack locomotion or perception, Theophrastus also classified them as hybrids of plants and stones (On Stones 53:38; Caley and Richards 1956).

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you (search for “token link” in inbox) before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.