September 2016

Vol. IV, No. 9

Ask a Near Eastern Professional: How the Sumerians Got to Peru

By Alex Joffe

Jerry Cohen asks “Is it true that an ancient bowl was found in Lake Titicaca in Peru that had Sumerian cuneiform writing on it? If so, what was its translation.”

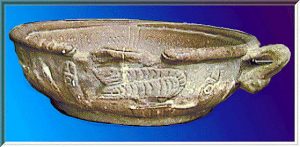

There was indeed a “Sumerian bowl” found in the late 1950s near Lake Titicaca, at the site of Hacienda Chúa, about 75 miles north of La Paz. The dark bowl has a prominent rim and a strap handle, is decorated with carved figures and geometric designs and, most significantly, has a sort of cuneiform inscription on the interior. One scholar translated the inscription, which deals with the Goddess Nia, and believes the bowl was produced by Sumerians and dates to around 3000 BCE.

Fuente Magna bowl

Exterior of bowl

Detail showing figure on interior

Fuente Magna inscription

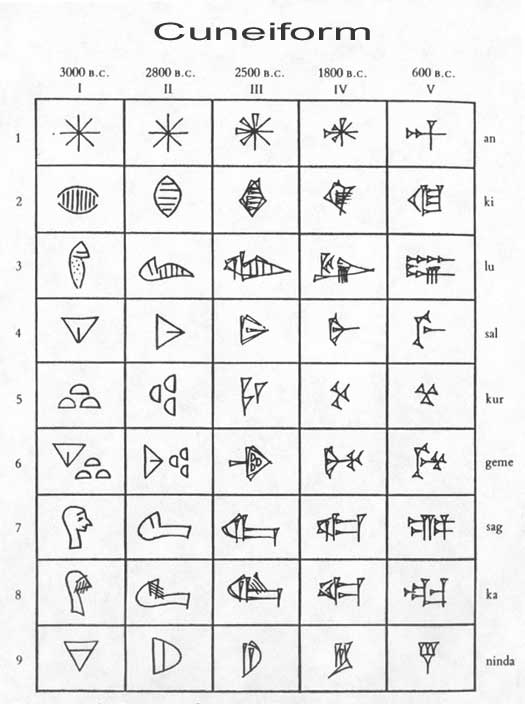

The problem however is that the object was not found in an archaeological excavation; it simply appeared. Another problem is that the bowl is utterly unlike any Sumerian object of the third millennium BCE, or the millennia before and after. The inscription is comprised of triangles and lines, reminiscent of Mesopotamian cuneiform writing, although not of the Sumerian period. But a closer look suggests the inscription is simply geometric filler or deliberate gibberish. And if anything, the face on the interior looks more like something produced by the local Tiwanaku culture (ca. 200-1000 CE).

Proto-cuneiform tablet

Changes in cuneiform script over time

In short, it’s not Sumerian. It’s either a modern fake or possibly an ancient local oddity (or something in between that has been modified with cuneiformish). So why does the ‘Fuente Magna’ bowl (it is unclear how it got the name) continue to resonate? There are several reasons.

For one thing, there is the question of contacts between the New World and the Old World. This is a vast topic. Humans evolved in the Old World (Africa, actually), left that continent for Asia, and eventually schlepped to the New World. The timing and circumstances of that movement continues to be debated but the evidence points to it occurring by 12,000 BCE.

Contacts after that, however, are hugely controversial, and various claims have been made for Africans, Egyptians, Phoenicians, Israelites, Romans, Arabs, Japanese, Chinese, Polynesians, and others visiting or settling in the Americas, all prior to the Norse reaching Newfoundland around the year 1000 CE.

The evidence brought to support such theories is often difficult to judge (such as purported similarities in myths), have alternate explanations (such as independent technological or stylistic developments), or are pretty clear fakes (such as the Phoenician ‘inscriptions’ in Brazil and Tennessee). The best we can say is that such contacts are not impossible but remain thus far unproven.

But how do we distinguish legitimate curiosity from unsavory agendas? Part of the answer here is to simply ask who is raising the questions and why. In the case of the Fuente Magna bowl, the first person to see it having a cuneiform inscription was apparently a Bolivian journalist, Mario Montaño Aragón, whose book Raices semíticas en la religiosidad aymara y kichua (Semitic roots in Aymara and Quechua religion) was published in 1979.

Not having seen the book it is hard to say whether this somewhat bizarre inquiry was in keeping with centuries of research that has sought ‘Semites,’ (including Israelites and ‘lost’ tribes’) as well as other ancient Near Eastern groups, settling around the world, from Britain to the Americas.

The desire to connect local cultures with the presumably ‘superior’ (or at least chronologically anterior) cultures of the Old World has many motives. For ‘British Israelites’ of the 19th century and a few Chinese of the 21st (who see their civilization founded by Egyptians), the exercise is connecting with myths of ancient nobility. Such interpretations may fly in the face of history as we know it (and indignant experts) but are really more articles of religious faith than anything else.

But all too often fringe interpretations have racist motives (the idea that local cultures couldn’t have developed without contact or guidance from ‘superior’ civilizations), or at least racialist ones. For example, the individual who ‘translated’ the Fuente Magna inscription as (proto) Sumerian, Clyde Winters, is a well-known Afrocentrist who believes that the Olmecs descended from Africans.

Here, unfortunately, we step further away from scientific method and consensus and towards the fringes. Winters’ ideas stitch together several theories and use data ranging from Greek mythology to genetics; that the Olmecs were black Africans (or Egyptians), that Atlantis was actually in Libya, that “neo-Atlanteans” founded settlements in Mexico, and much more. Each of these assertions is problematic if not extraordinary, with different types of evidence strung together breathlessly, to create a story that is extremely satisfying to the target audience.

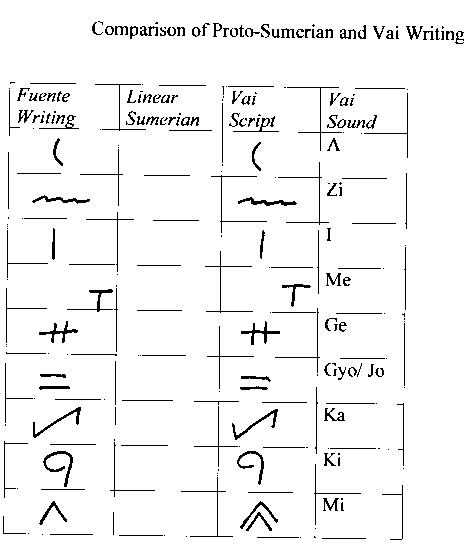

Winters’ ‘translation’ of the Fuente Magna ‘inscription’ is similarly extraordinary, relying on comparisons with a purported Saharan script that was also allegedly in common use in Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, and West Africa, and which is understood using the Vai script of Liberia, which was created only 1830. This method is completely unfamiliar to conventional scholarship, because it is not scholarly as such but rather a kind of Gnosticism, the recovery of esoteric knowledge with the power of redemption.

Winters’ associations between Sumerian and Vai

And that is part of the appeal of fringe challenges to academic paradigms and scholarly elites. The novelty of method matches the novelty of conclusions, all which sticks it to the mainstream that is either too dumb to recognize the truth or which suppresses it. The truth is out there, as Fox Mulder of the X-Files used to say. This applies to Bigfoot, the alien technologies that built the Pyramids, or the Nazi bases on the Moon. Secret truths are power in the minds of the enlightened few.

Now of course, new discoveries are being made all the time, and previously dismissed theories sometimes come to be recognized as correct. The idea of continental drift was proposed during the 1920s and was ridiculed until proven correct during the 1960s. And Pluto was happily ensconced as the ninth planet until recently when scientists cruelly downgraded it to a ‘dwarf planet.’

In archaeology new data have prompted continual revisions of how early the Americas were peopled. Confidently set at 9500 BCE during the 1960s, the date has marched further back time to the point where some respectable scholars suggest it may even have been 25 or 30 thousand years ago.

There are also gradual shift in paradigms, the result of evidence being patiently cataloged and pointed out by mainstream scholars, sometimes in the face of ridicule. Forty years ago scholars who pointed to the similarity of Greek and Near Eastern mythologies were on the margins, if not the fringe; now the question is how and why borrowings took place.

Non-specialists need to prod scholars who are too often married to (or hostage to, as some marriages are) their ideas. And scholars need to approach data honestly, without ideology or idealizing preconceived conclusions, and to continually reassess and rethink.

Thus far there is no meaningful evidence for Sumerian connections with the New World, and the Fuente Magna bowl, by virtue of being an unconvincing fake that teeters on an edifice of unfounded assumptions, doesn’t help the case. But looking carefully at how and why this case fails to persuade is a useful exercise, precisely for those reasons.

Alex Joffe is the editor of The Ancient Near East Today. He has a longstanding agreement to believe in the Loch Ness Monster if the Loch Ness Monster believes in him.