January 2018

Vol. VI, No. 1

When Life Gives You Lemons: Tracking the Earliest Citrus in the Mediterranean

By Dafna Langgut

Jaffa orange poster

One of the most famous Levantine exports of the 20th century was the Jaffa orange, and we have long associated the region with citrus. Today citrus orchards are a major component of the Mediterranean landscape and among the region’s most important cultivated fruits. But while citrus is now iconic, it may come as a surprise that it is not native to the Mediterranean Basin; these species originated thousands of miles away, in Southeast Asia. So how did the first citrus arrive in the Mediterranean, and why?

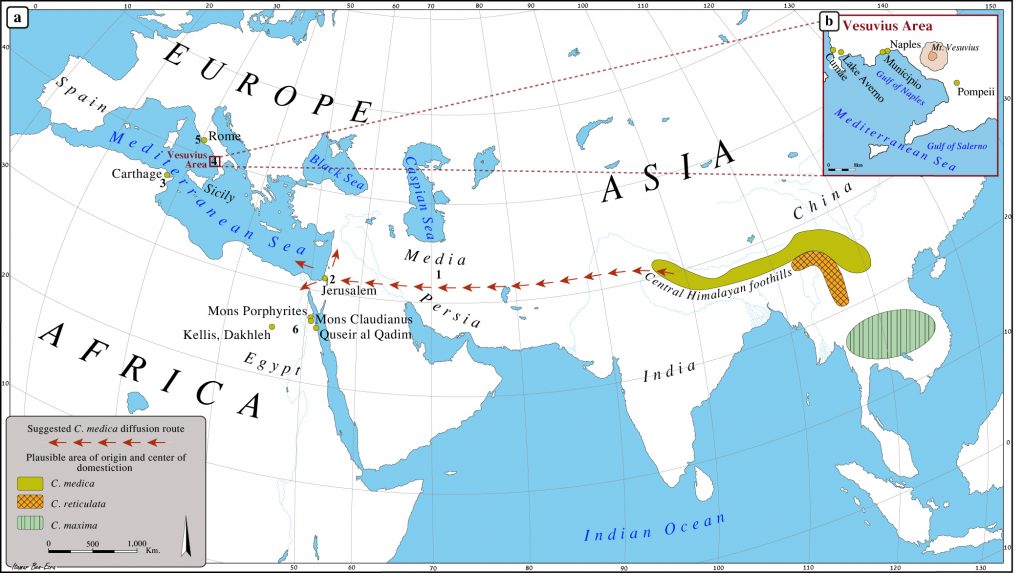

Citrus was first cultivated by humans at least four thousand years ago in Southeast Asia, and all cultivated species derive from a handful of wild ancestors. Several years ago I found the earliest archaeobotanical evidence of citrus within the Mediterranean in a royal Persian garden near Jerusalem dating to the fifth and fourth centuries BCE. In the course of research I traced the spread and diversification of citrus through a variety of historical information, including ancient texts, art, and artifacts such as wall paintings and coins, and by gathering all the available archaeobotanical remains: fossil pollen grains, charcoal, seeds, and other fruit remains.

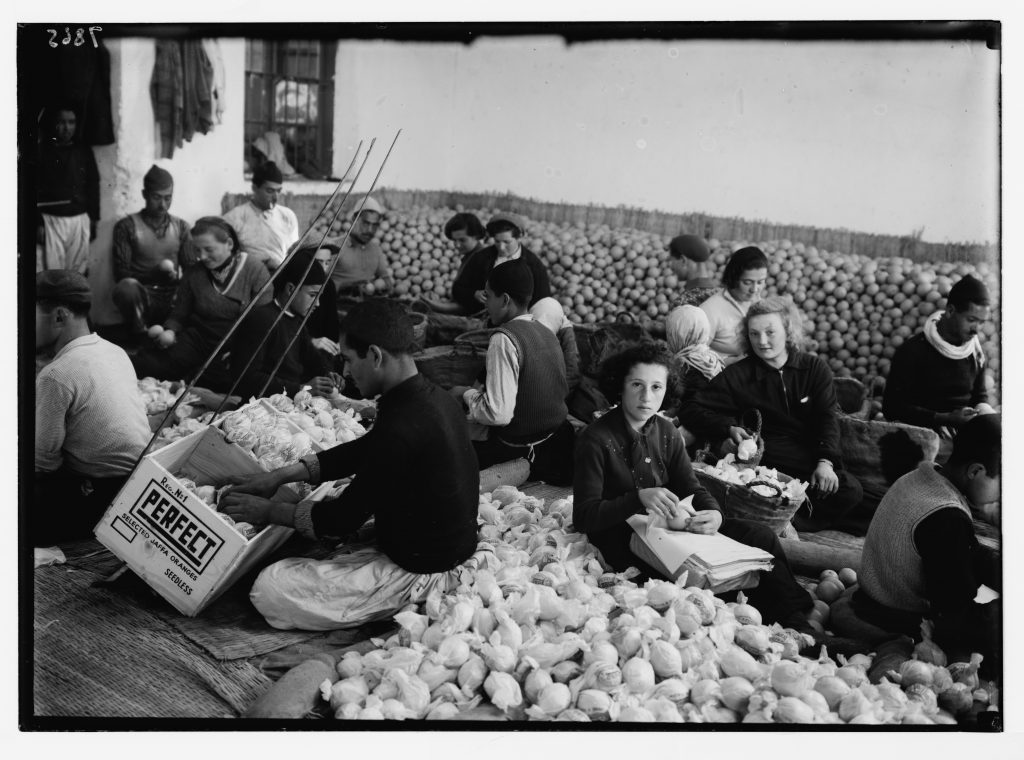

Packing oranges in Rehovoth by mixed crowds. Arabs and Jews (Library of Congress)

These botanical remains were evaluated for their reliability (in terms of identification, archaeological context and dating), and other possible interpretations. The data enabled me to understand the spread of citrus from Southeast Asia into the Mediterranean. The citron (citrus medica, better known in the Jewish tradition as the etrog) was the first citrus fruit to reach the Mediterranean, via Persia. The citron has a thick rind and a small, dry pulp, but it was the first to arrive in the west, and for this reason the whole group of fruits (citrus) is named after one of its less economically important members. It was introduced to the Eastern Mediterranean around the 5-4th century BCE and then traveled quickly west. The citron and the lemon (citrus limon, a hybrid of the citron and the bitter orange, which was introduced to the west at least four centuries later) were originally considered elite products. This means that for more than a millennium, citron and lemon were the only citrus fruits known in the Mediterranean Basin.

Citron fruits alongside a palm branch on a coin of the fourth year of the Great Revolt (69–70 AD). (B) Citron appears on a coin from the time of Simon bar Kokhba’s revolt (132– 136 AD).

Two citron fruits alongside a menorah in a magnificent mosaic from the sixth century AD Maon Synagogue (Negev Desert, Israel). Photograph by Clara Amit, courtesy of the Israel Antiquities Authority.

In contrast, sour orange, lime, and pummelo were introduced to the west much later beginning in the 10th century CE, by the Muslims, probably via Sicily and the Iberian Peninsula. It is clear that Muslims played a crucial role in the dispersal of cultivated citrus in Northern Africa and Southern Europe. This is also evident from the common names of many of the citrus types that are derived from Arabic. The dispersal of these fruits was possible because the Islamic world controlled extensive territory and commercial routes reaching from India to the Mediterranean.

Sour orange (Citrus page)

Lime (Citrus Pages)

The introduction of the sweet orange is dated even later, to the 15th century CE. Its arrival is probably linked with the trade route established by the Genoese and then in the 16 century CE by the Portuguese. The mandarin, one of the four core citrus species, was only introduced to the Mediterranean region at the beginning of the 19th century. Mediterranean cuisines that feature citrus are thus relatively recent developments, and their appearance in European (and American diets) even later. Today, the Mediterranean produces at least 20% of the world’s citrus.

Mandarin orange (Wikimedia Commons)

Pummelo (Wikimedia Commons)

The spread of these species, and their movement from elite to everyday status, shows how different cultures adapt unusual plants as status symbols of wealth and power, but then spread to all levels of society, influencing economics, diets and nutrition in the process.

Dr. Dafna Langgut is Head of the Laboratory of Archaeobotany and Ancient Environments at the Institute of Archaeology at Tel Aviv University.