THE ARCHAEOLOGY OF OLIVE OIL: EXCAVATING KHIRBET GHOZLAN IN JORDAN

Dr. Jamie Fraser, 2019 Harris Grant Recipient

On November 2, 2019, I drove up to a small knoll overlooking the stunning Wadi Rayyan in north Jordan, and started laying our trenches for the second field season of the Khirbet Ghozlan Excavation Project. Using funds generously awarded as a Harris Grant by ASOR, this project is asking new questions about the relationship between olive oil production and rural complexity in a period of urban recession known as the Early Bronze Age IV (EB IV, 2600-2000 BCE).

View to Khirbet Um al-Ghozlan in the Wadi Rayyan, Jordan. The monumental enclosure is visible running across the low saddle over which the site is accessed. Photo by Adam Carr.

Khirbet Um al-Ghozlan

Most archaeological surveys would classify the site of Khirbet Um al-Ghozlan (the “Ruins of the Mother of the Gazelles”) a farmstead, hamlet or village, as the site is a miniscule 0.4 ha in size. In this respect, Khirbet Ghozlan sits comfortably with our traditional understanding of the EB IV, which is described as a period of ruralization in which people abandoned large, fortified, mounded sites and dispersed into small, undefended villages.

However, Khirbet Ghozlan is remarkable for its monumental enclosure wall. Built partly as a double row of massive, megalithic slabs, this enclosure controlled access to the Ghozlan knoll. Why defend such a tiny site?

Excavations around part of the monumental enclosure wall. Note destruction by bulldozer (left). Orthophoto by Guy Hazell.

Olive oil and the EB IV

The answer probably lies in the site’s upland location. Khirbet Ghozlan is one of several EB IV enclosure sites, all located on the well-drained slopes of the Jordan Rift Valley escarpment. As these hills are well-suited to horticultural production, this project proposes that small enclosure sites served as specialized processing centers for upland tree crops such as olive (Olea europaea), and were defended to protect seasonally-produced stockpiles of high-value liquid commodities such as oil. In other words, could Khirbet Ghozlan be a 4,500 year-old olive oil factory and storehouse?

Excavating Khirbet Ghozlan

To test this model, a team from the British Museum and University of Sydney undertook excavations at Khirbet Ghozlan in March 2017 and November 2019.

Archaeologist Beau Spry excavating a broken-but-complete store jar in an EB IV storage compound. Photo by Adam Carr.

The results strongly support the olive hypothesis. Excavations uncovered a large architectural compound with several storage bins, and storage wares dominate the ceramic assemblage, including 26 partly-complete store jars and spouted decanting vats. Several long, notched Canaanean flint blades were possibly used as pruning saws, and four rock-cut olive presses were recorded nearby.

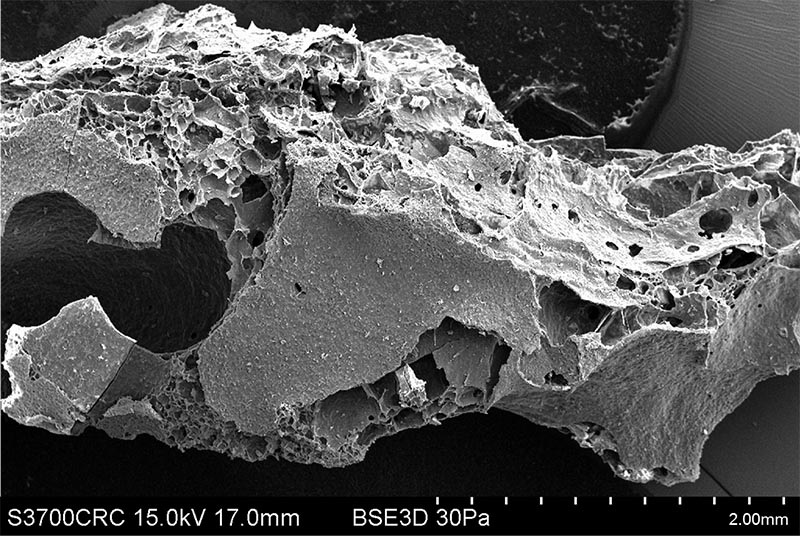

However, the most compelling data lies in the microscopic botanical remains. Using scanning electron microscopy, Dr Caroline Cartwright (Senior Research Scientist, British Museum), identified crushed olive stones and charred olive wood in the organic remains obtained through soil flotation. These data suggest that olive fruit was pressed for oil and olive wood was burned as fuel, likely stockpiled as orchard prunings.

Furthermore, the absence of other plant species such as domestic cereal grains and legumes suggests that people did not live at Khirbet Ghozlan permanently; rather, they probably visited the site seasonally to harvest and maintain their orchards. The single phase of unmodified architecture is consistent with limited occupation, and the paucity of domestic debris such as cooking pots and hearths suggests non-domestic activity.

Modern and ancient olive mills

Removing crushed olive paste (jift) from fibrous mat at the Toubneh olive mill after the oil has been pressed. Photo by Annette Dukes.

It was particularly thrilling to dig our trenches through this ancient olive factory at the same time as farmers were picking olives in the orchards that surround the site. Olives are harvested in October-November, after the first autumn rains wash away the summer dust. The fruit is pressed in local olive mills. Locked up for most of the year, these factories come alive each autumn, when they turn the olive harvest into oil for domestic consumption or local trade.

We were lucky to accompany the Jordanian Minister for Agriculture on a visit to a traditional olive mill in the village of Toubneh in north Jordan. Although oil extraction is now mechanized, the stages of washing, crushing and pressing are unchanged. The Toubneh mill was a powerful analogy for interpreting our discoveries at Khirbet Ghozlan – two seasonal olive factories separated by 4,500 years.

Additional links

Dr. Fraser presented a public lecture on this ASOR-funded project to ACOR in Amman on Oct 30, 2019. This lecture is available on-line at ACOR’s YouTube page here:

Olives and the apocalypse from Wendy John on Vimeo.

American Society of Overseas Research

The James F. Strange Center

209 Commerce Street

Alexandria, VA 22314

E-mail: info@asor.org

© 2025 ASOR

All rights reserved.

Images licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License