THE STUDY SEASON: THE LESS EXCITING, BUT STILL IMPORTANT COUNTERPART OF THE FIELD SEASON

Grant Ginson, 2018 Strange and Midkiff Families Excavation Fellowship Recipient

So you’ve dug, baulk trimmed, mapped, sectioned and backfilled. After a successful excavation season, you look back at all the objects, pottery and samples carefully removed and see that there is a lot of material to study. Sometimes, this material can be studied in the lab while being excavated. But an excavation produces lots of material and it cannot all be studied in a few weeks or even months. In these cases, it is necessary to have a season where you can study the material without having to deal with the necessities of a field season at the same time. This is where the study season comes in: it is an opportunity to engage and to expand the research for a project.

Through the generosity of the Strange and Midkiff Families Excavation Fellowship, I was able to participate for the first time on a study season this summer. The fellowship allowed me to travel to Jordan where I was a part of the Town of Nebo Archaeological Project. A young project, its inaugural season was in 2014, and 2018 was the second study season for the project. I took it as an opportunity to experiment and perform tasks that I never had time to do properly during a field season. This season, I expanded on something that has interested me since I had first seen it in action on a previous field season in 2016: photogrammetry. In 2016, I was shown the basics of photogrammetry and the program Agisoft Photoscan, which I used to create some preliminary models of objects, excavation squares and installations. That same year, I wrote a paper about mapping excavated objects in three-dimensional space using a GIS

program. This bestowed on me a desire to create models of excavated objects that could then be used to show their location after excavation in three-dimensional space. With that in mind, I set out to use this study season to create some models of excavated objects.

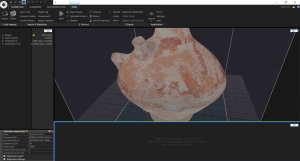

To create these models, I tried two different methods. The first involved a stationary object that would stay in the same spot while the camera rotated around it at a set distance and different heights. The second used a rudimentary lightbox that would provide an even light around objects and provide a crisp background of white to contrast with the objects being photographed. A turntable was then placed inside the lightbox to rotate objects in front of a stationary camera on a tripod. The first method worked fairly well but it had issues in that it was difficult to get the bottoms of objects and it had a lot of background noise. The second method created very good images that could be used to make complete models that included the bottom and had almost no background noise. Based on these results, I went ahead using the second method, as it was more efficient. There were still some issues with this method, the rudimentary setup meant that the lighting was not entirely even around the objects and there were some issues with keeping shadows off of the objects. To process the images, I decided to try a program called “Capture Reality” that I had heard about at the 2017 AIA conference in Toronto. The results were quite good; and are good enough models for representation and measurement. I experimented with different types of objects, corroded metal, stone mortars, ceramic figurines, basalt grindstones and pots. Each of these had issues that had to be overcome, but each was able to be made into a model by the end of the season. With this opportunity, I started something that will continue with the project: digitizing objects into digital models. As this was my role for the season, my days would typically be spent taking photos, processing data, prepping data and waiting for data to process. This may seem quite unexciting compared to the field season but it is quite necessary. There is a saying often

Setup two where the camera is stationary and the object is rotated on a turntable inside A lightbox.

quoted during excavation that ‘for every hour in the field, three hours are spent in the lab.’ The routine of the day made it hard to believe that I was there for five weeks, as each day became very similar to the last. Not going into the field also meant a much later wakeup at 8am to begin work rather than the usual 4am, giving me considerably more sleep than I was used to while in the field.

The study season is not all work all the time though, and there were new opportunities that could be taken since we were not tied down as much as by an excavation season. For one, it allowed for the visiting of a few other archaeological projects in the area, as well as journeying to the neighbouring country of Israel which I had never gotten to visit during an excavation season. The visits to other excavations broadened my knowledge of other projects as I got to witness how other sites excavate to meet the needs of each project’s research goals. Some look for artifacts down to 4mm and painstakingly look through all material to find as much as possible from the site. Others required a bit of a hike up a wadi (valley) to get to and had architecture that was difficult to distinguish from surrounding material. Others had different ways of setting up equipment like sifts. This also gave me the opportunity to meet other archaeologists and get to know their research and interests.

Through my experience I can say that, while definitely not as exciting as a field season, the study season can be just as fulfilling and rewarding. It has been a time to learn and a time to expand my knowledge. I have ASOR and the Strange and Midkiff Families Excavation Fellowship to thank for that.

Grant Ginson is a Wilfred Laurier University Archaeology grad who has worked in Jordan for three field seasons and in Canada for one field season. Grant hopes to use the experience he has gained through ASOR fellowships to continue his education at a graduate level by pursuing a Masters.

Project Links:

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/townofneboarchaeologicalproject/?hc_ref=ARTOew_41MsjGWLGNYdyS9ywPGhcBYbTNFUH8mys7EOr-d1a2LyahAxujKbOKxD4fh0&_rdc=1&_rdr

Twitter: https://twitter.com/neboarchaeology?lang=en

Website: http://www.townofneboproject.com/