Table of Contents for Bulletin of ASOR 381 (May 2019)

You can receive BASOR (and other ASOR publications) through an ASOR Membership. Please e-mail the Membership office if you have any questions.

Pp. 1–19: “The Terra-cotta Figurines from a Lamp Workshop at Khirbat Shumeila near Beit Nattif, Israel,” by Benyamin Storchan and Achim Lichtenberger

In 1934, excavations conducted at Beit Nattif, in the Judaean Shephelah region, uncovered a rich assemblage of waste from a terra-cotta lamp and figurine workshop.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

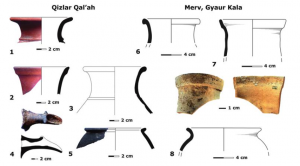

Pp. 21-40: “Correlated Change: Comparing Modifications to Ceramic Assemblages from Qizlar Qalʾeh, Iran, and Ancient Merv, Turkmenistan, during the Seleucid and Parthian Periods,” by Gabriele Puschnigg, Maria Daghmehchi, and Jebrael Nokandeh

From the Seleucid period onward, substantial transformations occurred in the ceramic assemblages from Qizlar Qalʾeh on the Gorgan Plain and ancient Merv (modern Gyaur Kala). Using

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 41-56: “Four Judean Bullae from the 2014 Season at Tel Lachish,” by Martin G. Klingbeil, Michael G. Hasel, Yosef Garfinkel, and Néstor H. Petruk

The article presents four decorated epigraphic bullae unearthed in the Level III destruction at Lachish during the 2014 season, focusing on the epigraphic,

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

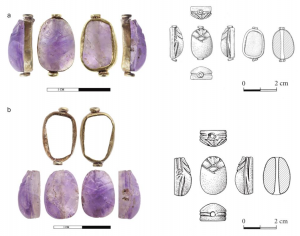

Pp. 57-81: “Uninscribed Amethyst Scarabs from the Southern Levant,” by Arlette David

Prompted by the discovery of a schematic uninscribed amethyst scarab at Tel Abel Beth Maacah in the Upper Galilee, an overview of such

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 83-105: “Foreign Food Plants as Prestigious Gifts: The Archaeobotany of the Amarna Age Palace at Tel Beth-Shemesh, Israel,” Ehud Weiss, Yael Mahler-Slasky, Yoel Melamed, Zvi Lederman, Shlomo Bunimovitz, Shawn Bubel, and Dale Manor

In contrast with the relatively rich documentation from the el-Amarna archive related to the main city-states of the southern Levant in the Amarna Age (Late Bronze Age IIA; 14th century b.c.e.), archaeological data from these sites is still wanting. This unfortunate situation highlights the importance of the

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 107-144: “Tel Yaqush—An Early Bronze Age Village in the Central Jordan Valley, Israel,” by Yael Rotem, Mark Iserlis, Felix Höflmayer, and Yorke M. Rowan

This article highlights the results of five excavation seasons at Tel Yaqush, Israel, conducted between the 1989 and 2000 on behalf of The Oriental Institute at The University of Chicago. Tel Yaqush was a medium-sized village, inhabited during the entire Early Bronze Age period, from the mid-4th to the mid-3rd millennia b.c.e. The excavations exposed a dense settlement

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

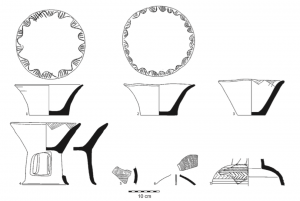

Pp. 145-162: “‘Crossing the Lines’—Elaborately Decorated Chalcolithic Basalt Bowls in the Southern Levant,” by Rivka Chasan, Edwin C. M. van den Brink, and Danny Rosenberg

The Late Chalcolithic period in the southern Levant shows a marked increase in symbolic expression. While most Late Chalcolithic basalt bowls are undecorated, notable

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 163-191: “Canaanite Reḥob: Tel Reḥov in the Late Bronze Age,” by Amihai Mazar, Uri Davidovich, and with an Appendix by Arlette David

Tel Reḥov, identified with Reḥob, was one of the largest Canaanite cities in the southern Levant during the Late Bronze Age (15th–13th centuries b.c.e.). Unlike many other Canaanite settlements, the city was founded in the 15th century after a hiatus beginning in Early Bronze Age III. In this article, four major Late Bronze Age occupation strata are described. Notable is

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 193-202: “Abracadabra, or ‘I Create as I Speak’: A Reanalysis of the First Verb in the Katumuwa Inscription in Light of Northwest Semitic and Hieroglyphic Luwian Parallels,” by Timothy Hogue

Previous translations of the Katumuwa Inscription have either rendered the first verbal phrase (qnt ly) “I commissioned for myself,” or “I acquired for myself.” No scholars have yet defended the possibility that it simply means “I made.” In fact, this is likely the case given the typical monumental rhetoric of Northwest Semitic and Hieroglyphic Luwian monumental inscriptions. In particular, a comparison with verbs of monumenting in Hieroglyphic Luwian inscriptions suggests that the monumenting phrase in the Katumuwa Inscription was calqued on a Luwian phrase. This difference is significant because it reveals an important aspect of the inscription’s monumentality and the Syro-Anatolian conception of the stele. The stele that Katumuwa created was not understood merely as the inscribed object. Rather, the monument was the conjunction of material object, ritual engagement, and the resultant manifestation of the monument’s commissioner. There was no monument apart from Katumuwa, whose voice was preserved in the inscription and whose presence could be reactivated through ritual. Therefore, Katumuwa did in fact “create” the stele as he spoke through it to his monument’s users.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

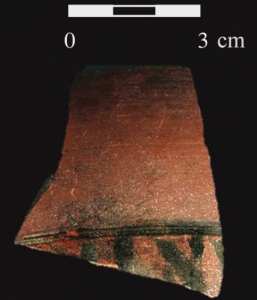

Pp. 203-210: “An Inscribed Sherd in Aramaic Script from Barikot, Pakistan,” by Michael Zellmann-Rohrer and Luca Maria Olivieri

This article discusses a sherd inscribed with a text in Aramaic script from Barikot in Pakistan. The site, known in classical sources on Alexander the Great, has been regularly

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 211-236: “An Eighth-Century b.c.e. Gate Shrine at Tel Lachish, Israel,” by Saar Ganor and Igor Kreimerman

Excavations conducted on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority at Tel Lachish exposed the southern half of the six-chambered gate in Level III. In the eastern chamber, a gate shrine was uncovered. The shrine was split in two: a larger northern room and a smaller southern room. The southern room, which served as the holy of holies, had a niche in its southern wall in front of which a double altar was placed. Dozens of bowls and oil lamps were revealed inside the shrine. At some point, evidently prior to the destruction of Level III by Sennacherib in 701 b.c.e., the shrine was desecrated

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this issue. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the the entire issue, including book reviews, on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.