Table of Contents for Near Eastern Archaeology 81.1 (March 2018)

Subscription Options

You can receive NEA (and other ASOR publications) through an ASOR Membership or through an Individual Subscription. Single issues (subject to availability) are available for purchase, with ASOR members receiving a discount. Please email us if you have any questions.

Pp. 4-5: “The Survey of the Site and Its Insights,” by Joe Uziel and Aren M. Maeir

Since its infancy, archaeological research has used survey as a major tool in both regional studies (see, e.g., Conder and Kitchener 1881) and as a tool for project planning.

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 6-14: “New Insights into the Philistines in Light of Excavations at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath,” by Louise A. Hitchcock and Aren M. Maeir

Even though the arrival of the Philistines in the southern Levant is an event that happens “off camera,” that is, before the appearance of their settlement remains, it is an

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

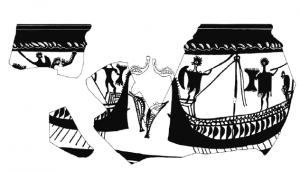

Pp. 15-18: “Philistine Decorated Pottery at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath,” by Linda G. Meiberg

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 19-21: “Philistine Burial Customs in Light of the Finds at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath,” by Joe Uziel and Aren M. Maeir

Despite over a century of research conducted on the Philistines and their material culture, a very small quantity of finds relating to their burial customs has been reported.

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 22-23: “What Language(s) Did the Philistines Speak?,” by Brent Davis

The evidence that we have for the language(s) spoken by the Philistines is not plentiful, but what we do have is interesting (though far from conclusive). Two types of evidence predominate: (1) inscriptions from Philistine sites (thus these inscriptions may have been produced by Philistines), and (2) Philistine words and names borrowed into other languages of the region and recorded (however imperfectly) in non-Philistine records.

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 24-27: “Microarchaeology at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath, Area A,” by Steve Weiner and Elisabetta Boaretto

The overall objective of archaeological excavations is to extract as much reliable information as possible from the whole archaeological record: both macroscopic and

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 28-33: “Excavations in Area D of the Lower City: Philistine Cultic Remains and Other Finds,” by Amit Dagan, Maria Eniukhina and Aren M. Maeir

During the first decade of the Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath Excavation Project, various areas in the upper city were excavated. Based on the results of the surface survey, however, it

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

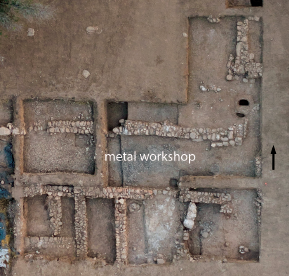

Pp. 34-36: “Iron Age Metal Production at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath,” by Adi Eliyahu-Behar and Vanessa Workman

While the increasing appearance of iron objects between the late twelfth and early eleventh centuries B.C.E. has been the greatest indicator for the shift from bronze to

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 37-40: “Women in Distress: Victims of the Iron Age Destruction at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath,” by Marina Faerman, Aren M. Maeir, Amit Dagan and Patricia Smith

The widespread signs of destruction and fire seen at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath in the upper and lower parts of the city (Namdar et al. 2011; Zukerman and Maeir 2012) include the charred skeletal remains of three women found in Area D, Stratum D3, and five individuals found in Area A, Stratum A3. All appear to have been victims of the same event, namely, the destruction of the city at the end of the ninth century B.C.E. by Hazael of Aram (Maeir 2012). We provide here a detailed description of these remains and the circumstances surrounding their deaths using standards published in Bass 1995 to determine their age and sex, and the Munsell color chart (Ellingham et al. 2015) to estimate the extent and pattern of burning on the bodies.

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 41-44: “Iron Age Animal Husbandry at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath: Notes on the Fauna from Area D,” by Ron Kehati, Amit Dagan and Liora Kolska Horwitz

Faunal remains comprise a significant portion of finds recovered from most archaeological sites in Israel. Among other issues relating to factors such as animal evolution and ecology, their examination can elucidate past human diet, symbolic and cultural behavior, technology relating to animals and animal products, as well as the site’s environment and even paleoclimate of a region (e.g., Reitz and Wing 2008; Russell 2011). These issues were considered when we examined the faunal assemblage recovered from the late Iron Age I (tenth century B.C.E.) through Iron Age IIA-B (post-830 B.C.E.) deposits excavated in Area D at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath.

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 45-47: “Expanding the Lower City: Area K at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath,” by Eric L. Welch

Excavations in the lower city of Gath have been ongoing since 2009. In Area D, in the westernmost excavated portion of the lower city, excavations have demonstrated the

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 48-54: “Judahite Gath in the Eighth Century B.C.E.: Finds in Area F from the Earthquake to the Assyrians,” by Jeffrey R. Chadwick and Aren M. Maeir

After Philistine Gath fell to the Arameans in the late ninth century B.C.E. (Maeir 2008; 2012: 47–48) the huge city atop Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath was a ghost town for several decades. Some structures had been burnt or otherwise destroyed, but many were simply abandoned to the elements. As years passed, winter storms and the processes of nature eroded the roofs and walls of hundreds of ownerless houses and other buildings. The devastation was alluded to by the Judahite prophet Amos when he predicted the eventual demise of Samaria: “Go down to Gath of the Philistines,” he challenged the Israelites, to behold what complete desolation is like (Amost 6:2; Maeir 2004). Aside from the presence of a few squatters who settled in the north lower-city ruins near the Elah riverbed, the forlorn ghost town of Gath slowly decayed away, until a cataclysmic earthquake shook the entire region somewhere around 760 B.C.E. (Chadwick and Maeir, forthcoming; Maeir 2012:49–50).

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 55-58: “Textile Production at Iron Age Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath,” by Deborah Cassuto

Textiles in antiquity were multifunctional, and used much as they are in modern times.1 When we think of textiles, our first thoughts are of clothing. In antiquity, as in modern times, clothing demonstrated social status (e.g., royal, common), occupation (e.g., priestly, military) and ranged from simply constructed frocks to finely manufactured prestige garments. Textiles were also used as furnishings, such as rugs, wall carpets, cushions, and curtains, as boat sails and shelters, or sacks for storage or carriage. In short, they were consumed by everyone for a multitude of needs, ranging from the mundane to the festive, from the functional to the opulent.

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 59-62: “Iron Age Adornment at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath,” by Josephine A. Verduci

Between 1998 and 2014, Iron Age strata from Areas A, C, D, E, F, and P yielded a rich assemblage of 172 objects of adornment. These objects come from contexts dated to the Late Bronze Age-Iron Age transition through to Iron Age IIB. Tomb T1, containing the skeletal remains of over 70 individuals (adults and children) and dated to late Iron I-early Iron IIA, also yielded a large and varied assemblage of 154 adornment objects, not including 65 items of shell that were most likely also used as items of adornment. Among these 326 objects, are examples of metal, stone, and vitreous materials, which are represented by beads, pendants, rings, bangles (bracelets, anklets, and armlets), earrings, and fibulae.

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 63-65: “Petrographic and Technological Analysis of the Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath Pottery,” by David Ben-Shlomo

In archaeological research, pottery analysis is of importance for relative dating and reconstructing daily life, as well as for understanding trade patterns and cultural contacts. Trade patterns in table ware and commodities carried in pottery containers can help illuminate the economy and administration of an ancient society. The production technology of pottery, and especially its mode of production, can also reflect social, economic, and political realities in a general manner. However, according to many ethnographic and archaeological studies, the technology of pottery production is relatively conservative, and does not change rapidly.

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 66-71: “Cooking Installations through the Ages at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath,” by Shira Gur-Arieh

While it is debated when exactly humans began regularly to cook their food (Sandgathe and Berna 2017), it is clear that once they did, they never looked back. Cooking raw

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

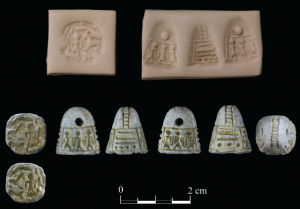

Pp. 72-76: “Seals and Sealings at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath,” by Stefan Münger

The currently published glyptic assemblage from Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath comprises more than sixty seals and sealings (Keel 2013: 94–123; see also Maeir, Shai, and Kolska

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 77-80: “Plant Use in the Bronze and Iron Ages at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath,” by Suembikya Frumin and Ehud Weiss

The long history of settlement at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath provides an opportunity to study changes in vegetation and its use in different cultures and periods, as well as aspects relating to local biodiversity over time. These changes may shed light on the local development of agriculture, on cultural changes, on ancient human migrations, and foreign influences. Analyzing archaeological data from several time periods and cultures within the same landscape offers new directions in the study of past cultures, and the origins of their formation (Frumin et al. 2015; Frumin 2017). In the case of the appearance of Philistine culture, which occurred partly through migration, this type of data enables analysis of invasion events using archaeological data, with the aim of reconstructing changes in diet, land use, and in regional and interregional linkages associated with a specific migrant culture.

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 81-84: “What We Can Learn from the Flint Industries at Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath,” by Francesco Manclossi and Steven A Rosen

Within Levantine archaeology, the analysis of chipped stone tools from the Metal Ages is reasonably well established. Chipped stone tool manufacture is a reductive process, leaving large quantities of diagnostic waste products, allowing detailed reconstruction not only of the specifics of technologies and function, but also of such issues as on-site/off-site production, trade, and degrees of craft specialization—and ultimately offering insights into social and economic processes not always available from other sources. The materials from Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi/Gath from the Early Bronze (EB), Late Bronze (LB), and Iron Ages (IA) provide a long-term view of these processes at the site, and offer a case study for larger-scale processes.

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 85-91: “‘The Archaeological Picture Went Blank’: Historical Archaeology and GIS analysis of the Landscape of the Palestinian Village of Tell eṣ-Ṣâfi,” by Liora Kolska Horwitz, Rona Winter-Livneh and Aren M. Maeir

Referring to the dearth of historical archaeological research in Israel, in Between Past and Present: Archaeology, Ideology, and Nationalism in the Modern Middle East,

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

To view the entire issue on JSTOR, click here.