TABLE OF CONTENTS FOR BASOR 378 (NOVEMBER 2017)

Subscription Options

You can receive BASOR (and other ASOR publications) through an ASOR Membership or through an Individual Subscription. Single issues (subject to availability) are available for purchase, with ASOR members receiving a discount. Please email us if you have any questions.

Pp. 1-23: “Cup-Marks and Citadels: Evidence for Libation in 2nd-Millennium B.C.E. Western Anatolia,” by Christina Luke and Christopher H. Roosevelt

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 25-53: “Early Ottoman Archaeology: Rediscovering the Finds of Ascalon (Ashkelon), 1847,” by Edhem Eldem

Very little is known about the acquisitions of the (Ottoman) Imperial Museum during the first decades of its existence. As a

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 55-69: “Seismic Environments of Prehistoric Settlements in Northern Mesopotamia: A Review of Current Knowledge,” by Eric R. Force

Historical archives, modern instruments, and archaeological excavations at plate-boundary sites have recorded an intricate—at times, seemingly relentless—recurrence of severe earthquakes related to the northward movement and convergence of the Arabian tectonic plate with neighboring plates. Based on such information, it is possible to contour average earthquake frequency and/or severity across the northern Mesopotamian region within about 200 km from the plate boundaries.

The environments of the Late Neolithic and Chalcolithic habitations of this area range seismically from very active to nearly quiescent; however, not a single excavation report from sites therein considers seismic hypotheses for recorded damage. Exceptionally detailed excavation reports of tells located in two contrasting seismic environments nevertheless show some evidence more consistent with seismic damage than with other causes. The record for Tepe Gawra in the more active area suggests severe earthquakes closely clustered in time. In both areas, there is evidence of some earthquake damage averaging every 500 years or less, and almost all Halaf sites and Halaf-to-Ubaid transitions in northern Mesopotamia plot in areas where such frequencies are expected. Expected seismicity derived from the voluminous historical and instrumental records should play a prominent part in the interpretation of archaeological evidence of this region, as in others near tectonic plate margins.

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

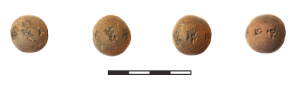

Pp. 71-94: “Contexts and Repetitions of Cypro-Minoan Inscriptions: Function and Subject Matter of Clay Balls,” by Silvia Ferrara and Miguel Valério

This article follows the trail of previous suggestions that the so-called clay balls inscribed in the Cypro-Minoan script bear personal

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 95-111: “Administration, Interaction, and Identity in Lydia before the Persian Empire: A New Seal from Sardis,” by Elspeth R. M. Dusinberre

A stamp seal excavated at Sardis in 2011 is a local product dating to the period of the Lydian Kingdom. It was found in a churned-

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 113-125: “A Brand New Old Inscription: Arad Ostracon 16 Rediscovered via Multispectral Imaging,” by Anat Mendel-Geberovich, Arie Shaus, Shira Faigenbaum-Golovin, Barak Sober, Michael Cordonsky, Eli Piasetzky and Israel Finkelstein

Arad Ostracon 16 is part of the Elyashiv Archive, dated to ca. 600 B.C. It was published as bearing an inscription on the recto only. New multispectral images of the ostracon have enabled us to reveal a hitherto invisible inscription on the verso, as well as additional letters, words, and complete lines on the recto. We present here the new images and offer our new reading and reinterpretation of the ostracon.

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

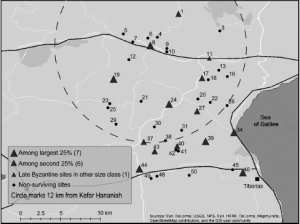

Pp. 127-143: “Population Contraction in Late Roman Galilee: Reconsidering the Evidence,” by Hayim Lapin

Based on detailed archaeological survey, Uzi Leibner argued that there was a substantial decline in population in late antique Galilee. This article reviews the evidence from the survey, making use of standard quantitative methods, and points to non

A predominant proportion of the pottery was produced at a single site (Kefar Ḥananiah), and these forms generally have a higher sherd count than non–Kefar Ḥananiah forms. As sherd count is strongly correlated with the number of sites at which a form appears, assessments of the survival and population of sites based on proportions of pottery is distorted by the distribution of Kefar Ḥananiah pottery, which can be shown to decline with distance. Once we control for distance, site size also appears to be an important factor in the proportions of pottery from every period. Although these factors taken together do not necessarily negate Leibner’s conclusion, they do necessitate a reevaluation.

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

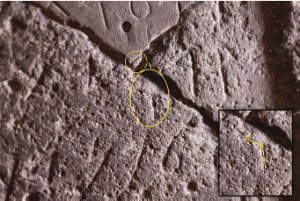

Pp. 145-162: “RYT or HYT in Line 12 of the Mesha Inscription: A New Examination of the Stele and the Squeeze, and the Syntactic, Literary, and Cultic Implications of the Reading,” by Aaron Schade

This article presents arguments in favor of reading ryt in line 12 of the Mesha Inscription. A new examination of the stele and

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 163-202: “The Circles Building (Granary) at Tel Bet Yerah (Khirbet el-Kerak): A New Synthesis (Excavations of 1945–1946, 2003–2015),” by Raphael Greenberg, Hai Ashkenazi, Alice Berger, Mark Iserlis, Yitzhak Paz, Yael Rotem, Ron Shimelmitz, Melissa Tan and Sarit Paz

New excavations conducted in the Circles Building (Granary) at Tel Bet Yerah, first excavated in 1946, form the basis for a revised,

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

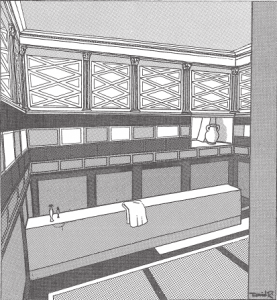

Pp. 203-222: “Phoenician Bathing in the Hellenistic East: Ashkelon and Beyond,” by Kathleen Birney

Excavations of a Hellenistic neighborhood at Ashkelon revealed a suite of heavily plastered rooms, one with a mosaic floor,

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

To view the entire issue on JSTOR, click here.