A REFLECTION ON THREE YEARS OF OCCUPATION BY ISIL

By Dr. Ali. Y. Aljuboori

Dean of the College of Archaeology, Mosul University

Sr. Cultural Heritage Adviser, ASOR CHI

June 10. 2017

I am writing this article on June 10, 2017. Exactly three years ago, Mosul fell into the hands of ISIL.

On June 10, 2014, Mosul University was in the middle of final exams. At noon, the University ordered everyone to go home before the army and police began to enforce a curfew. At that time we heard that ISIL had entered western Mosul. By midnight they controlled the mayor’s office, the central bank, and all of the other major government buildings.

Over the course of the next morning, I saw many people leaving, including soldiers from the local military base who had thrown off their military uniforms and equipment in order to blend in with civilians. I told my son to flee with his wife and two children. My wife and I stayed behind.

At first, ISIL did not change much. Then, around a month after the conquest, they began to impose Shari’a law. ISIL treated different faiths in different ways. Sunni Muslims had to pay new Islamic taxes while Shi’a Muslims were killed. Other religious groups had three choices: convert to Islam, pay special taxes, or be killed. Every Friday at noon ISIL held public executions by decapitation or hanging as punishment for any resistance or disorder. In this cruel way, they controlled the people of Mosul.

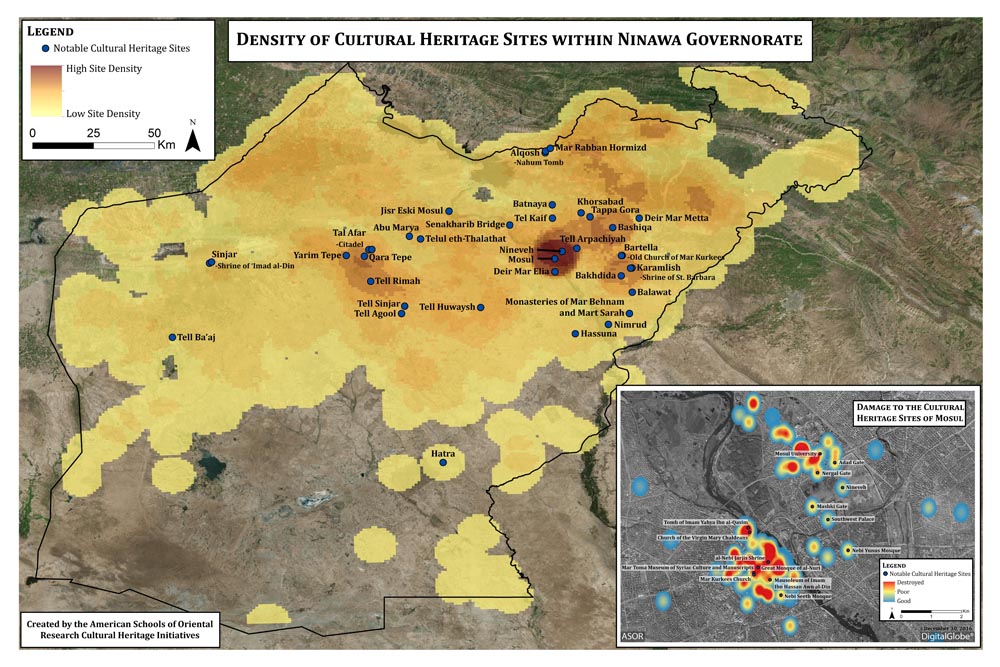

Density of Cultural Heritage Sites in Nineveh Province (Susan Penacho, ASOR CHI)

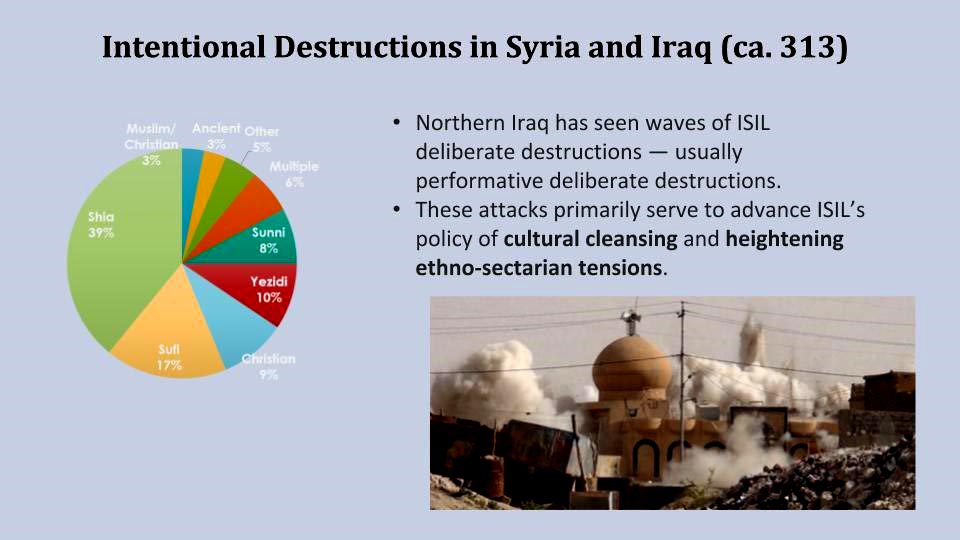

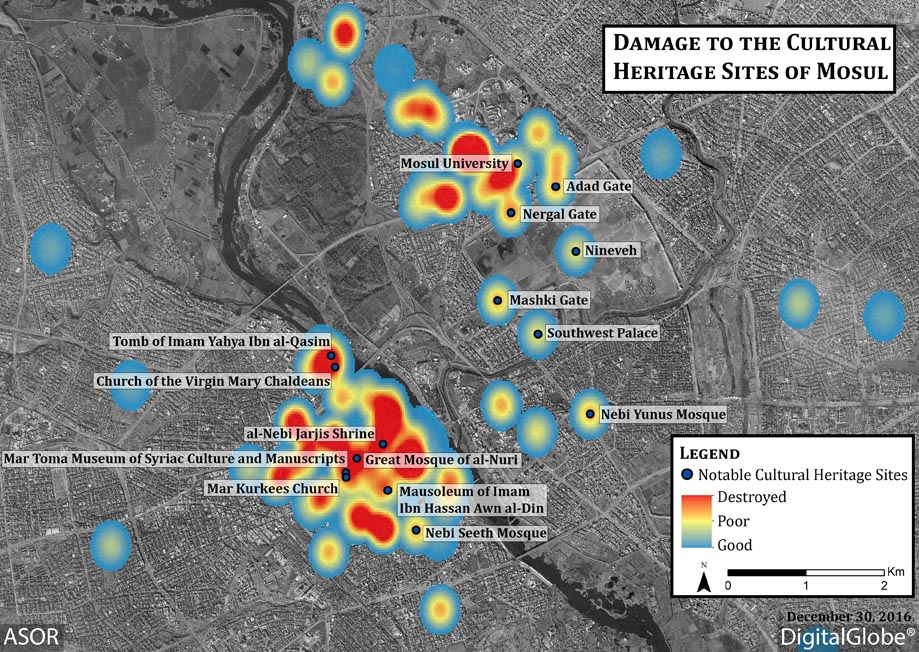

Under ISIL, education and culture in Mosul and Nineveh Province suffered terribly. Shortly after they took over, ISIL began to blow up mosques, churches, and Yezidi shrines. This included Nebi Yunus Mosque, which they destroyed with explosives in July 2014.

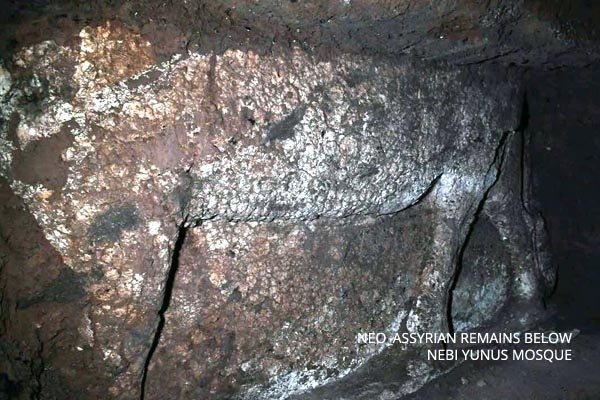

In 2015 they started to erase our ancient heritage. In addition to the destruction of the Neo-Assyrian palace at Nimrud, they demolished the Nergal, Adad, and Mashki gates in the city wall of Nineveh as well as looted and smashed the collections of the Mosul Museum. They also started to dig tunnels into the mound below Nebi Yunus Mosque, which contained the remains of a Neo-Assyrian palace. In these tunnels they discovered inscribed stone reliefs of the Neo-Assyrian king Esarhaddon, a relief depicting a series of ladies, bull colossi, and other small finds from the Neo-Assyrian period.

Ratio of Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage in Iraq and Syria (Susan Penacho, ASOR CHI)

ISIL also attempted to eliminate access to any knowledge that they considered un-Islamic. Schools and universities remained closed after the conquest. They burned the collections of the Public Library of Mosul and the Central Library of Mosul University.

Damage to Cultural Heritage Sites in Mosul (Susan Penacho, ASOR CHI)

However, knowledge persevered. Many teachers and professors fled to Dohuk, Erbil, and Kirkuk. Once there, they began to teach again. By October 2014, Mosul University had secondary locations in Dohuk and Kirkuk so that students could continue to learn.

Since January 15, eastern Mosul has been free from ISIL control. Life is beginning to gradually flourish once again. In February, the University of Mosul began classes for those who live in eastern Mosul. By July 1, all staff and faculty in the territory of the Kurdistan Regional Government will be back in Mosul and the secondary locations of Mosul University will be closed. The University intends to begin regular classes in October.

I have lived through many violent events in Iraq’s history. The destruction of the ancient and modern cultural heritage in Nineveh Province was an astonishing and sad moment that is impossible for me to describe. Now that ISIL is gone, my colleagues and I will do our best to restore what our nation has lost.

Editorial Comment: Dr. Ali Aljuboori is the Dean of the College of Archaeology of Mosul University and acts as a Senior Cultural Heritage Adviser for Iraq with ASOR CHI. Dr. Aljuboori is currently coordinating an ASOR CHI digital preservation initiative in the Mosul area to preserve textual collections. The project, funded by the Whiting Foundation, brings together the Hill Museum and Manuscript Library (HMML) and the Centre Numérique des Manuscrits Orientaux (CNMO) to preserve thousands of years of writing, Dr. Aljuboori is an expert in the ancient languages of Iraq and has most recently published the first Arabic-Sumerian dictionary.