WELCOME TO THE ASOR BLOG

WELCOME TO THE ASOR BLOG

The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) is the preeminent society for individuals interested in the archaeology of the eastern Mediterranean and the Biblical Lands. This blog is intended to facilitate ASOR’s mission “to initiate, encourage and support research into, and public understanding of, the cultures and history of the Near East from the earliest times.”

My Time at a Roman-Era Jewish Settlement

By Jill Marshall, 2016 William G. Dever Fellowship Recipient

Thanks to ASOR’s William G. Dever Fellowship for Biblical Scholars, in Summer 2016, I traveled to Israel to participate in the Shikhin Excavation Project and to conduct research at the Albright Institute in Jerusalem. Since my research is in New Testament and early Christianity, I chose Shikhin because it is a Roman-era Jewish settlement that gives scholars insight into the socio-economic landscape of the Galilee. Directed by James R. Strange of Samford University and Mordechai Aviam of Kinnaret Academic College, the excavation reveals interesting details about ceramic production and the interactions between cities (Sepphoris) and villages (Shikhin) in the Roman period.

A newbie to archaeology, I arrived in Nazareth with the early crew so that I could get a crash course in excavation methods, stratigraphy, and record keeping. With the instruction of Dr. Strange and Randy O’Neill, the field supervisor, I soon was able to measure and string a square and identify changes in soil color, composition, and consistency.

The next week, we began on the main field of the site, on a hill overlooking the Beit Netofa Valley and with a clear view of that city on a hill Sepphoris (Tsipori). I was the area supervisor for Square 14, at the northeast corner of the field. We opened three other squares, and the crew got to work clearing, measuring squares, and digging. Most of the crew were college students from Samford University in Alabama.

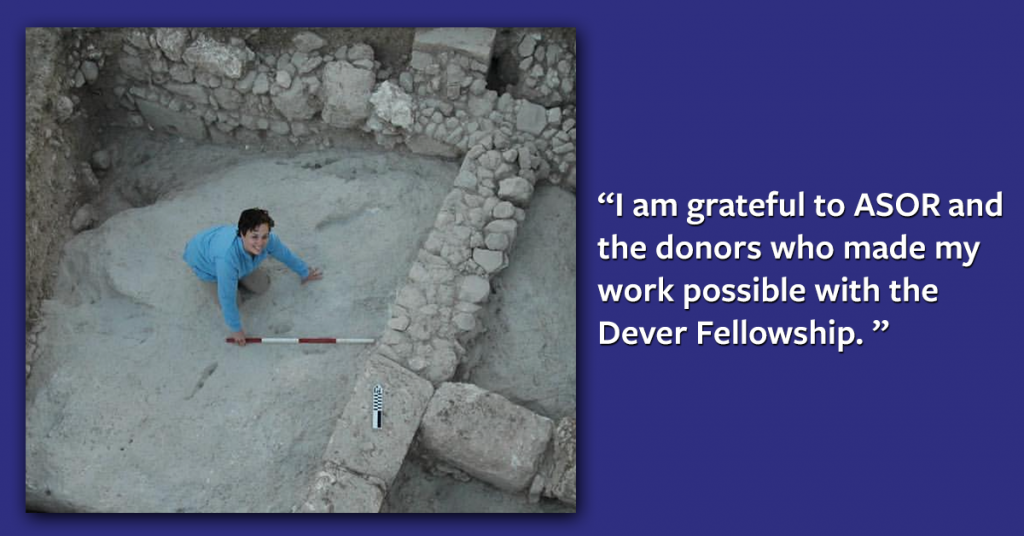

My square had been opened the previous year, and we could see the outline of stone walls, what seemed to be a pit, and a lot of tumble. As we cleared, the walls came into focus and seemed to be constructed at different times, with both large cut stones and small cobblestones. The “pit” provided many lamp fragments and whole lamps, consistent with the character of the site. The previous season yielded numerous whole lamps and lamp molds in a room that appeared to be a workshop. One square excavated this year, to the southeast of Square 14, had an interesting installation that appeared to be a potter’s wheel and work table, again reaffirming the hypothesis about pottery production. In addition to lamps, the site has yielded many “wasters”—pottery fragments that were damaged in production, whether misfired, cracked in firing, or with air bubbles baked into the piece. This is also good evidence that pottery production was occurring at the site, and Dr. Strange is working to classify and record the various forms of wasters at Shikhin. The production of pottery and lamps at the site leads to intriguing questions about trade: Where were these products traded? How were trade networks established and maintained? And, for my purposes, how was trade integrated with the spread of cultural and religious ideas?

As we excavated Square 14, we came upon a plaster floor in part of the area, which indicated that this section may have been indoors, or, more probably, given the floor’s poor construction, an outdoor workspace or courtyard. The plaster floor posed challenges for excavation: We scraped a lot of dirt off of dirt and became acquainted with the differences between plaster, dirt, dirty plaster, plastery dirt, limestone, limestone pretending to be plaster, and dirt that really wanted to be limestone. What we thought was a pit was in this section of the square, and it may actually be a cistern that continued into the area to the south and west of our square. Shikhin has several cisterns, two of which another team excavated this season. The cisterns that they excavated are located under what may be a synagogue—or at least a massive building with a monumental threshold, the only architectural part of the building that remains. The cistern team, with their hard hats, ladders, and pulleys, found many whole lamps, jugs, and other pottery, as well as Hellenistic silver coins.

Each day, we arrived at the site around 5:00 am, and—surprisingly, as I’m not a morning person—the mornings flew by: It was cool, and we had great energy to be productive. At 8:30 am, James F. Strange (“Abuna”) and Carolyn Strange joined the team and brought second breakfast, the best meal of the day. Abuna, who directed the University of South Florida excavations of Sepphoris until 2010, made the rounds and gave us insights from his years of excavation in the region. The Stranges fostered an encouraging and supportive community during our month in the field, which made a world of difference for the students. Such community-building led not only to a productive research season but also to a productive learning experience for the students and me. Samford is lucky to have a new crop of experts in reading pottery, soil, and artefacts, who are able to evaluate their findings and make conclusions about the culture and society of ancient Galilee.

All in all, this summer was a great introduction to archaeology in the Galilee. I am grateful to ASOR and the donors who made my work possible with the Dever Fellowship. I hope to return to Shikhin soon.

Jill Marshall received her PhD in Religion from Emory University. Her research focuses on women’s religious activities in early Christianity and the ancient Mediterranean world, particularly inspired speech, prophecy, divination, and prayer. She is currently working on a book on women’s prophecy in early Christian literature.

WELCOME TO THE ASOR BLOG

WELCOME TO THE ASOR BLOG