What Can Mythological Narratives tell us about Mycenaean Long-Distance Trade in the Bronze Age?

February 2023 | Vol. 11.2

By Jörg Mull

Locations of Mycenaean Pottery Finds in the Mediterranean basin. Map by Olav Ode.

The Late Bronze Age (ca. 1600 to 1150 BCE) was a time of unprecedented economic activity in human history, spurred on by the supply and production of the eponymous alloy bronze on an almost industrial scale. The supply networks for copper and tin, the components of true bronze, stretched over large parts of western Eurasia and included long-distance maritime transport during this period.

The palatial centers of Mycenaean Greece were positioned at a unique geographical interface between the cultural centers of the eastern Mediterranean as well as the metal supply sources in the western Mediterranean, northern Europe, and the Black Sea area. There are archaeological, historical, and epigraphic indications that the Mycenaean Greeks somehow contributed either directly or indirectly via intermediaries to the exchange of goods in the second half of the 2nd millennium BCE:

(Left) Mycenaean three-handled jar, ca. 1500-1300 BCE, found at Agrigento in Sicily (Photo: Zde, CC By-SA 4.0)

(Right) Charioteer Vase”, a Mycenaean import found at Tel Dan, Israel, ca. 14th century BCE. (Photo: Israel Museum, Jerusalem)

Archaeological evidence: Mycenaean pottery has been found all around the Mediterranean basin. These finds, however impressive, do not in all cases automatically prove that the Mycenaeans brought the ceramics to these remote locations themselves. The pottery could also have been brought to the various destinations by intermediaries.

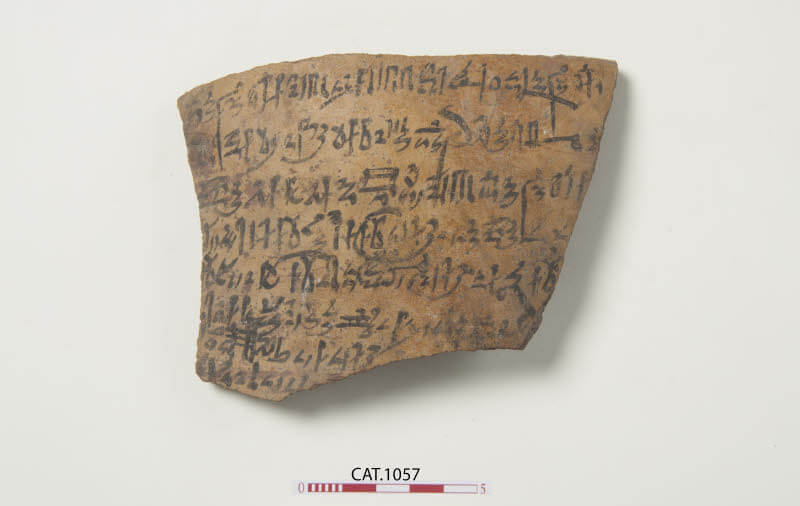

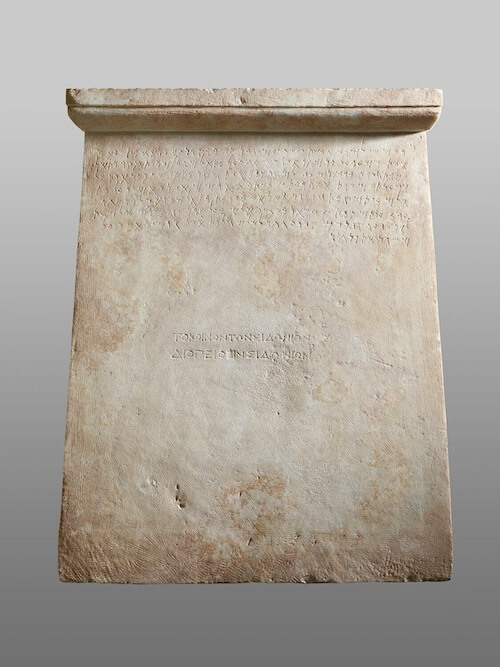

Historical and epigraphic evidence: Written documents from the Late Bronze Age that mention the Mycenaeans are still few and far between. Mycenaeans may have been occasionally mentioned in Egyptian diplomatic correspondence as Tanaju (Danaans) and in Hittite texts as Ahhiyawa (Achaeans). Inscriptions in Egypt (e.g. from Kom el-Hetan) indicate a degree of familiarity on the Egyptian side with destinations in the Aegean. Additionally, some Linear B inscriptions in Mycenaean palaces seem to mention some toponyms in the Mediterranean and the Black Sea area. The available historical and epigraphic material is subject to interpretation, often selective, and thus not able to provide a comprehensive view of Mycenaean trading and traveling activities.

Overall—and partially due to the above-mentioned limitations of archaeological and historical evidence—the degree to which the Mycenaean Greeks conducted long-distance commercial journeys themselves to participate in the metal trade of the period is still disputed. However, there is one corpus of material that has not been given enough attention in the debate: the later mythological tradition.

In my recent book, Towards the Borders of the Bronze Age and Beyond, I analyzed the large corpus of Greek myths that contains evidence of long-distance journeys of Mycenaean pioneering adventurers. Many of the myths are very likely to go back to Bronze Age roots. For instance, in the 8th century BCE, Homer extensively quotes older myths that preceded his account of the Trojan War and which may have been initially transmitted verbally over centuries (following the Oral Theory of Parry and Lord). Potential later distortions and re-interpretations of myths especially during the colonial age of Greece sometimes make it difficult to identify the Bronze Age nuclei. Yet, we still have access to a large corpus of ancient mythological transmission by various mythographers and historiographers over the Archaic, Classical, Hellenistic, and Roman periods of Greece with a high degree of intertextuality.

Papyrus fragment from Tell el-Amarna showing soldiers wearing Mycenaean-style boar tusk helmets, 14th cent. BCE. (British Museum EA74100; ©Trustees of the British Museum)

The transmitted mythical stories of Mycenaean explorers on the metal trading routes of the Late Bronze Age can provide supporting evidence to answer the still-open question of direct Mycenaean involvement in the exchange of goods, especially metals, during the Late Bronze Age. In particular, the analysis of these texts with regard to the regional reach of Mycenaean exploration shows by and large a high degree of consistency with the archaeological evidence.

In the eastern Mediterranean, frequent contact between Mycenaeans and other peoples is embedded in a rich mythological heritage, with the respective older myths mostly focusing on topics of origin and descent. The transmission reveals a high degree of familiarity with the region and its inhabitants and is not consistent with a picture of Mycenaeans only relying on intermediaries for travel and trade. For example, the Bellerophon myth as a “first mover” account with respect to Anatolia coincides broadly with the beginning of Mycenaean expansion abroad. In the myth, transmitted to us by Homer, Bellerophon (son of Glaucus and grandson of Sisyphus) was sent away to Lycia in southwest Anatolia (having gotten into trouble in Corinth and Argos), where he embarks on a number of adventures, such as battling the chimaera.

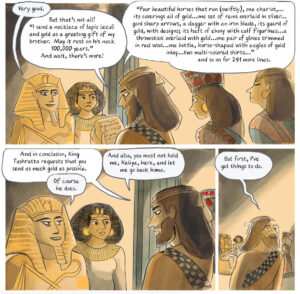

Regarding contacts with Egypt, the mythological tradition of Belus and Agenor (transmitted, e.g., by Apollodorus) depicts genealogical ties between rulers of Egypt and the Levant, likely referencing the Second Intermediate period when a dynasty of Semitic origin ruled the Nile Delta. Actually, the mythical transmission indicates earlier direct visits of Mycenaeans to the Nile (from ca. 1550 BCE onwards) compared with the existing archaeological and historical record—mythological contacts predate the archaeological and historical evidence by about a century.

The mythological record for the areas in the western Mediterranean in terms of topics is different and focuses on explorations and “first movers”. Geographical targets are often metal production areas in the various regions. For example, the mythological record contains references to the establishment of a metal trading colony on Sardinia, such as in the stories about Herakles and his nephew Iolaus told by Diodorus Siculus. There are also references to trips to the Iberian Peninsula by the heroes Perseus and Heracles just at the point in time when (in historical terms) the trading route on the Atlantic Ocean began to open up again (i.e. from ca. 1350 BCE onwards).

As for other regions, Italy is an interesting lacuna in terms of “first mover” or exploration myths, as archaeological evidence shows that it was relatively well-known to the Mycenaeans. In the Black Sea region, archaeological materials of Mycenaean origin are relatively scarce, although this may be due in part to the limits of modern archaeological exploration. The myth of Phrixus and Helle (children of Athamas, king of Boiotia, as told by Apollodorus) points to Mycenaean travel to the Pontic region. Based on genealogical chronology, Phrixus and Helle should be placed around 1250 BCE. Access to the Black Sea may have been a relatively late event in Mycenaean history and only possible after political and nautical obstacles were cleared.

Further destinations of metal supply, like northern Europe (Hyperborea), may even have been known to the Mycenaeans indirectly via contacts with other traders and travelers. A considerable amount of scholarly speculation regarding direct contacts between Mycenaeans and Britain via the “Atlantic route” is still not backed up by sufficient archaeological evidence.

A common thread among many of the connected myths are frequent metaphors about “flying” to remote destinations (e.g. Pegasus, the Ram of Phrixus, Daidalos’ wings, Perseus’ flying Sandals). These metaphors may stand in for a new type of fast-moving ship, which allowed the Mycenaeans access to faraway destinations. Based on literary and other evidence, it has been estimated that these ships, the standard size being the “pentekonter” with 50 rowers, could theoretically travel up to 200km a day in ideal conditions. An average of 50 to 80km/day for long distances seems more likely, taking into consideration crew fatigue and rest. The colorful language used in the mythological tales may help to express the wonder at the long distance of these journeys felt by a sedentary population at home.

In sum, a holistic view of Mycenaean overseas contacts that includes the mythological heritage shows clear evidence of Mycenaean long-distance travel and exploration contained within the corpus of Greek myths, with a focus towards the metal supply centers of the age in Sardinia, southern Iberia, and the Black Sea area. Combined with the archaeological evidence, this helps strengthen the case for Mycenaean long-distance trade in the Bronze Age and points to where future work should continue.

Jörg Mull is the author of Towards the Borders of the Bronze Age and Beyond: Mycenaean Long Distance Travel and its Reflection in Myth (Sidestone Press 2022). He studied Greek and Latin and holds a Doctorate in Economics.

How to cite this article

Mull, J. 2023. “What Can Mythological Narratives tell us about Mycenaean Long-Distance Trade in the Bronze Age?” The Ancient Near East Today 11.2. Accessed at: https://anetoday.org/mull-myth-narrative-trade/.

Want to learn more?

Osiris Must Die – Understanding the Practice of “Menacing the Gods” in Ancient Egyptian Magic

Post a comment