Table of Contents for Near Eastern Archaeology 83.2 (June 2020)

You can receive NEA (and other ASOR publications) through an ASOR Membership. Please e-mail the Membership office if you have any questions.

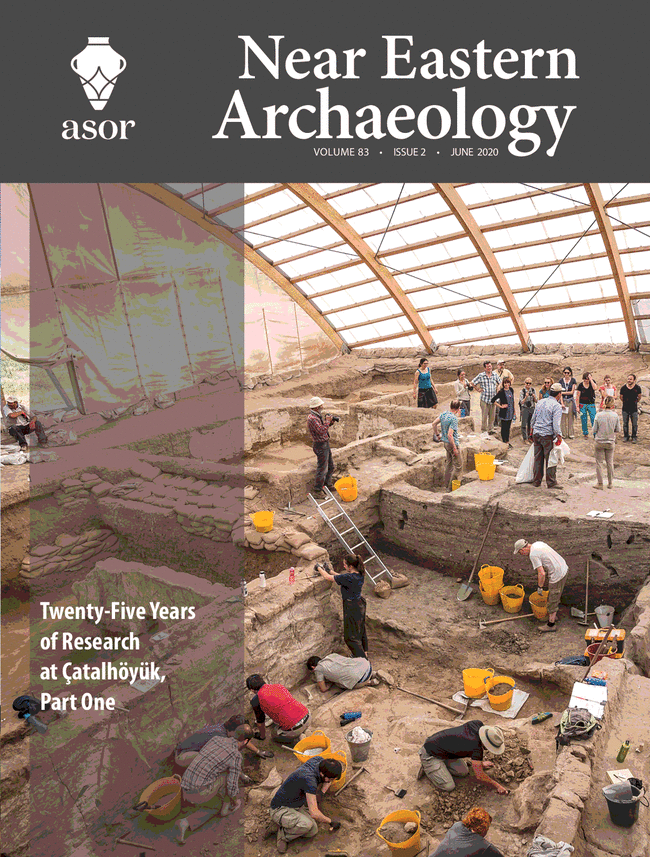

Pp. 72-79: “Twenty-Five Years of Research at Çatalhöyük,” by Ian Hodder

Çatalhöyük is a 9,000 year-old tell site in central Turkey. First excavated by James Mellaart in the 1960s (e.g., 1967), a new project began in 1993 (Hodder 1996, 2000). At first the focus was on surface study and survey, and excavation began in 1995. Excavation ended in 2017 and there was a study season in Catania, Sicily, in 2018. This introduction summarizes the work over the last twenty-five years and describes some of the results outlined in the ensuing articles of this issue of NEA. An additional set of results will be published in the September 2020 issue.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 80-87: “Integrating Magnetic and GPR Survey at Çatalhöyük,” by Kristian Strutt, Stefano Campana, Jessica Ogden, Gianluca Catanzariti, and Gianfranco Morelli

As part of the 2010 and 2012 field seasons at the site of Çatalhöyük, geophysical survey was conducted with the aim of mapping parts of the subsurface remains at the site. While extensive excavations have been conducted on the East Mound, a considerable part of the area of this mound is still largely unknown in terms of the presence of archaeological deposits and possible Neolithic structures.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 88-97: “Çatalhöyük and Its Landscapes,” by Gianna Ayala and John Wainwright

T he landscape surrounding the site of Çatalhöyük has been transformed by centuries of land use and agricultural improvements. The most recent transformations started in the early twentieth century aiming to improve agricultural productivity by carrying out extensive irrigation and land-reclamation programs (Roberts 1990). Irrigation water was brought via the Beyşehir-Sugla canal system which was completed around 1911 (Money 1919), bringing irrigation water from Lake Beyşehir to the south. Further regulation of water supplies in the 1950s and 1960s included the construction of the Apa Dam on the Çarşamba River (completed in 1962) and World Bank support for extending irrigation schemes. Unsurprisingly, archaeological and palaeoenvironmental evidence from Çatalhöyük suggests significantly different environments at the time of occupation from that of the modern landscape. Therefore, it is essential for archaeological interpretations to be underpinned by robust palaeoenvironmental reconstructions.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 98-109: “The Seasonality of Wetland and Riparian Taskscapes at Çatalhöyük,” by Jesse Wolfhagen, Rena Veropoulidou, Gianna Ayala, Dragana Filipović, Ceren Kabukcu, Carla Lancelotti, Marco Madella, Kamilla Pawłowska, Carlos G. Santiago-Marrero, and John Wainwright

Seasonal variation in the natural world of Neolithic Çatalhöyük shaped the organization of daily life and the social world of its residents. Seasonal cycles in climatic patterns, hydrology, growing seasons of wild and domestic plants, and seasonal behaviors of herded, hunted, and gathered animals would have affected the overall productivity of the landscape and consequently the rhythms of social life (e.g., Fairbain et al. 2005; Pels 2010). These created social conceptions of seasonal patterns and activities shaped the ways in which people interacted with their local environments and structured the timing and spatial requirements of everyday tasks.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 110-119: “Common Ground: Reevaluating Open Spaces at Çatalhöyük,” by Justine Issavi, Kamilla Pawłowska, Milena Vasić, and Rena Veropoulidou

Investigations of open spaces within the context of the Southwest Asian Neolithic are varied in approach and in how explicitly they center these spaces within the study. The term “open space,” for this article, refers to any space not covered by an architectural feature such as a roof or other permanent covering. Open spaces have variously been discussed as arenas of daily or utilitarian activities, shared property or communal space, places of ritual, public spaces, courtyards (yards), conduits for movement, or undifferentiated spaces.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 120-128: “Thermal Alterations to Human Remains in Çatalhöyük,” by Cassie E. Skipper, Scott D. Haddow, and Marin A. Pilloud

The Neolithic East Mound at Çatalhöyük, dating to 7100–5950 cal BCE (Bayliss et al. 2015), in central Anatolia is well known as a large, early agricultural village. Like other Neolithic sites in this region, the site had distinct mortuary practices, which at Çatalhöyük are dominated by primary interments beneath house floors, accounting for 83 percent of stratified individuals recovered to date (Haddow et al. in press). While commingling of skeletal elements due to repeated use of house platforms as burial locations is common (Boz and Hager 2013; Haddow, Sadvari et al. 2016), there is also evidence of secondary burial practices including post-interment cranial retrieval and the occurrence of loose and partially articulated skeletal elements moved from a previous location (Haddow and Knüsel 2017). Such observations suggest the practice of delayed burial for certain individuals, a pattern that appears to increase in frequency over time (Haddow et al. in press).

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.