Table of Contents for Near Eastern Archaeology 83.1 (March 2020)

You can receive NEA (and other ASOR publications) through an ASOR Membership. Please e-mail the Membership office if you have any questions.

Pp. 4-15: “Tel Burna after a Decade of Work: The Late Bronze and Iron Ages,” by Chris McKinny, Aharon Tavger, Deborah Cassuto, Casey Sharp, Matthew J. Suriano, Steven M. Ortiz, and Itzhaq Shai

As our project at Tel Burna enters the tenth season of excavations, we have compiled a summary of the archaeological finds from 2009–2018. Tel Burna is located in the southern Shephelah in modern-day southern Israel. The Judean Shephelah is comprised of foothills above several east–west valleys that drain the Judean incline in the east to the coastal plain in the west. These valleys were strategic agricultural zones and trade routes throughout history, and in particular during the Late Bronze and Iron Ages. Tel Burna is situated on a natural hill in the middle of Nahal Guvrin, one of the main roads through the Judean Shephelah.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 16-29: “Niğde Kınık Höyük: New Evidence on Central Anatolia during the First Millennium BCE,” by Lorenzo d’Alfonso, Burak Yolaçan, Lorenzo Castellano, Nancy Highcock, Roberta Casagrande-Kim, Maria Elena Gorrini, and Andrea Trameri

The sudden fall of the Hittite Empire at the turn of the thirteenth century BCE is a major case study for political disruptions in the history of the Mediterranean, and it resulted in the profound transformation of central Anatolia, the former Hittite core territory.1 This disruption affected the whole eastern Mediterranean, but nowhere was hit as severely as Hittite Anatolia. Hittite political legacy survived only at the eastern borderlands of the empire—the Upper Euphrates, Malatya, and Karkemiš—and only to the tenth century in northern Syria and south of the Taurus Mountains (fig. 1; Weeden 2013). As for central Anatolia, scholars generally concur that a degree of political complexity was reintroduced only in the eighth century BCE. Famine, mass migrations, and conflicts have been considered the main driving factors behind the sudden decrease in settlement occupation after the fall of the empire.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 30-37: “The Late-Antique Ma‘agan Mikhael B Shipwreck, Israel,” by Deborah Cvikel

The Ma‘agan Mikhael B shipwreck, dated to the seventh–eighth centuries CE, is located about 70 meters off the Mediterranean coast of Israel, at a maximum water depth of 3 meters, buried under 1.5 meters of sand. The excavation of the shipwreck is in progress, and the hull has not yet been excavated completely. The exposed hull remains, comprising the keel, endposts, aprons, framing timbers, hull planks, stringers, bulkheads, and maststep assembly, are in a good state of preservation. The most significant finds are the ceramic sherds and complete amphorae. Other finds include rigging elements, wooden artifacts, organic finds, animal bones, glassware, coins, bricks, and rocks. The dating of this shipwreck makes it an exceptional source of information regarding various aspects of ship construction, seamanship and seafaring, regional economic activity, and daily life in the Levant in late antiquity.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 38-45: “The Dispersal of the Domestic Cat: Paleogenetic and Zooarcheological Evidence,” by Claudio Ottoni and Wim Van Neer

Domestication is one of the most interesting and challenging processes in human and animal evolution. The fundamental change in subsistence strategies from hunting and gathering to farming that took place for the first time in the Levant more than ten thousand years ago profoundly changed human culture and biology, and set the groundwork for population growth, migrations, the rise of civilizations, and wealth disparities (Bocquet-Appel 2011; Gignoux, Henn, and Mountain 2011; Kohler et al. 2017).

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 46-55: “(Un)Dressing Children in the Lachish Reliefs: Questions of Gender, Status, and Ethnicity,” by Kristine Garroway

The Lachish reliefs were once part of Room XXXVI in Sennacherib’s Southwest Palace at Nineveh. R. D. Barnett made the claim that the Lachish reliefs represented an actual event, the siege and destruction of Lachish by Sennacherib in 701 BCE, and was not some stock depiction of the defeat of an enemy city, an assertion that David Ussishkin (2014) has verified. Monumental palace reliefs functioned in a variety of ways, and these reliefs in particular were meant as royal propaganda. Those entering Sennacherib’s palace would see that to resist the power of the Assyrian army was futile (Uehlinger 2003). Since few people could read, it was important that the actions shown on the wall monuments were self-explanatory, and “the participants and location easily recognizable” (Franklin 2001: 261).1 It follows then that the depictions of the people on the reliefs also portray a general picture of the parties involved (Uehlinger 2003: 263).

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

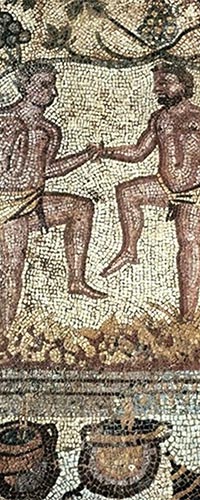

Pp. 56-64: “Wine from the Desert : Late-Antique Negev Viniculture and the Famous Gaza Wine,” by Sára Lantos, Guy Bar-Oz, and Gil Gambash

One of the most prestigious wines of late antiquity was Gaza wine, which, like Ashkelon wine, became popular in the late fourth century and reached peak demand in the second half of the fifth–early seventh centuries CE. The appetite for this and other southern Levantine wines arose as a result of several influential processes, leading among them the growth of the new capital at Constantinople and its positive economic effect on the eastern Mediterranean (Ostrogorsky 2003: 59; van Dam 2010: 77). More specifically, the growing popularity of Christianity, and the rise of both the pilgrimage movement and the ascetic communities, served as efficient platforms for familiarizing the Mediterranean world with wines originating in the Holy Land. With the spread of the ritual of the Eucharist, wine from the Holy Land gained particular sanctity. While the western part of the Mediterranean may have been lost to the empire, the new kingdoms that now controlled the region adopted essential elements of Mediterranean routine and Roman culture, including Christianity, and the wine trade between the eastern and western parts of the Mediterranean continued to prosper regardless of political changes (Chrysos 1997: 18; Pohl 1997; Lebecq 1997; Halsall 2007: 19–22; Brown 1971: 144).

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.