Table of Contents for Near Eastern Archaeology 82.3 (September 2019)

You can receive NEA (and other ASOR publications) through an ASOR Membership. Please e-mail the Membership office if you have any questions.

Pp. 132-139: “Exile and Return of the First Temple Vessels: Competing Postexilic Perspectives and Claims of Continuity,” by Debra Scoggins Ballentine

Jerusalem’s destruction and the Babylonian exile were catalysts for the composition and redaction of much Judean literature. Authors wrestled with disruption of cultus and the uncertainty of returnees having to sort out their place—both physical spaces and abstract social places—back in Jerusalem and Judah. Stories about the temple vessels feature competing claims about their fate: that they were dismantled or left intact during the exile; that they were stored in a Babylonian temple or used as Babylonian wine goblets; that they were returned to Jerusalem with divine protection; and even that they were temporarily displaced once back in Jerusalem. These varied fates reflect competition between groups and individuals—both historical figures and literary characters—such as Jeremiah, Daniel, Ezra, and Nehemiah. Postexilic authors employed stories about the vessels to privilege particular forms of ritual, endorse select groups and ideologies, and undercut alternative positions.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 140-147: “Another Temple, Another Vessel: Josephus, the Arch of Titus, and Roman Triumphal Propaganda,” by Nathaniel DesRosiers

In 71 CE, the year after the destruction of the second Jerusalem temple, the victorious emperor Vespasian and his son Titus, commander of the Judean

campaign, celebrated their success with a victory triumph through the streets of Rome. Josephus provides a full account of the event in The Jewish War 7.123–58, lingering in particular on his description of the spoils of the Temple as they were paraded through the streets. He states: “The spoils were piled in heaps, but prominent above all were the spoils from the temple in Jerusalem, these included a golden table many talents in weight and a lampstand likewise made of gold” (JW 7.148).

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 148-155: “When Yosa Meshita Took the Temple Menorah: A Rabbinic Legend,” by Steven Fine

The rabbis of late antiquity were well aware that after the destruction of the Second Temple the most precious “sacred vessels” had been taken to Rome. Classical rabbinic literature records numerous legends of the destruction including discussions of the fate of the sacred vessels, including “a golden menorah.” At times preserving distant memories of the war, these stories are most significant for the ways that later generations lived with and interpreted the continuing meaning of this national trauma. In this essay I will employ anthropological/folklore approaches better to understand rabbinic texts. That is, I examine the human characters who wrote, performed, heard, and read these traditions in late antiquity (Hasan-Rokem 2003; Fine in press). I focus on the authorship and reception of rabbinic tradition by late antique audiences by undertaking a “thick description” of a story preserved in Genesis Rabbah, a collection of homiletical midrashim assembled in the Galilee near the turn of the fifth century CE. I focus on the treason of a certain Yosa Meshita, suggesting contexts in which this tale “lived,” situating it within the world in which it was authored, performed, and achieved its literary form.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 156-163: “Facing the Holy Ark, in Words and in Images,” by Steven D. Fraade

The ark of the covenant was central to the plan of the Jerusalem Temple and the wilderness tabernacle before it, as the vessel was located in the structures’ holiest, innermost domain. Despite its importance, the ark of the covenant was invisible to virtually all Israelites. Even while the ark was being assembled, disassembled, and transported in the wilderness, the Levitical Kohathites were instructed to shield it from view, including their own (Num 4:5–20). One of the chief obligations of Aaron and his descendants was to deny access to anyone else, including the Levites, to the Holy of Holies, which housed the ark alone, or risk death (Num 18:1–7, 22–23).

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 164-171: “When Is a Menorah Not Just a Menorah? Rethinking Menorah Graffiti in Jewish Mortuary Contexts,” by Karen B. Stern

Hundreds of representations of menorahs have been uncovered from across the ancient world, throughout Egypt, Asia Minor, the Black Sea, Malta, North Africa, Europe, Arabia, Judaea, Palaestina, and Syria. Studied intently by historians, these depictions testify to the symbol’s historical importance, longevity, and myriad uses in antiquity. Many scholars have speculated that the menorahs evoke messianic ideas or those of resurrection; others argue that they signify divine presence or the cosmos at large. Recurring representations of menorahs in modern Jewish religious contexts, in all cases, have assured that the menorah remains the most recognizable of all the temple vessels to modern audiences.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

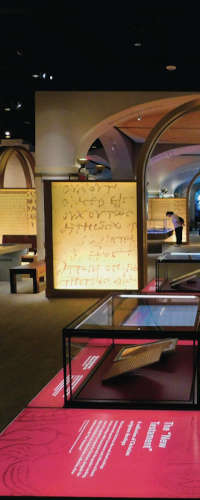

Pp. 172-178: “Remembering the Destruction(s) of the Temple at the Museum of the Bible,” by Cavan Concannon

Tucked away on the fifth floor of the Museum of the Bible (MOTB) in Washington, DC is a worn stone, weighing roughly a ton. Unlike most museum exhibits, this one invites visitors to touch its rough surface. The stone would be unremarkable but for what it was made to support: the terrace of the Second Temple in Jerusalem. The stone is on loan to the MOTB as part of an exhibit called “The People of the Land: History and Archaeology of Ancient Israel” by the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA). It once formed part of the Western Wall, the massive terrace that supported Herod the Great’s expansion of the Second Temple complex. As visitors touch this piece of the “temple,” they accept the MOTB’s invitation to a pilgrimage experience. As one evangelical news site put it, “It’s an opportunity to get a glimpse of the Holy Land without visiting the Middle East” (Stahl and Mitchell 2017).

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 179-185: (Exhibit Review) “The World Between Empires, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,” by Stephanie Lynn Budin

This past March I had the grand opportunity to visit this exhibit curated by Blair Fowlkes-Childs and Michael Seymour, which ran from March through June 2019. The intent of the exhibit was twofold. On the one hand it provided a survey of the various cities, states, and societies that populated the Middle East between the great empires of Rome to the west and Parthia to the east (thus the title of the exhibit), ranging in date from the first century BCE to the mid-third century ce. Of particular interest was how these communities situated between dominant and domineering cultures formed their own identities through the mixture of indigenous and imported traditions, and how these identities were expressed. Thus the placard welcoming visitors to the exhibit reads: Following a journey along ancient trade routes across the Middle East, the exhibition explores how local life and culture were shaped by diverse cities and communities, and how identities were expressed through art.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 186-189: “Third Workshop on Gender, Methodology, and the Ancient Near East: Enhancing Networking and Consolidating an Initiative,” by Katrien De Graef, Agnès Garcia-Ventura, Anne Goddeeris, and Saana Svärd

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above report on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.