WELCOME TO THE ASOR BLOG

WELCOME TO THE ASOR BLOG

The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) is the preeminent society for individuals interested in the archaeology of the eastern Mediterranean and the Biblical Lands. This blog is intended to facilitate ASOR’s mission “to initiate, encourage and support research into, and public understanding of, the cultures and history of the Near East from the earliest times.”

Most Popular ASOR Summer Posts

[Recap]

Summer is coming to an end, and students and teachers are getting back into the groove of the classroom. So, we thought we’d answer that age-old question, “What did you do this summer?” with a look back at the five most popular blog posts on the ASOR Blog.

We had a lot of really great authors contribute to our blog over the last few months. Now the “votes” are in–here are the most clicked on and viewed articles on the ASOR Blog from this summer …

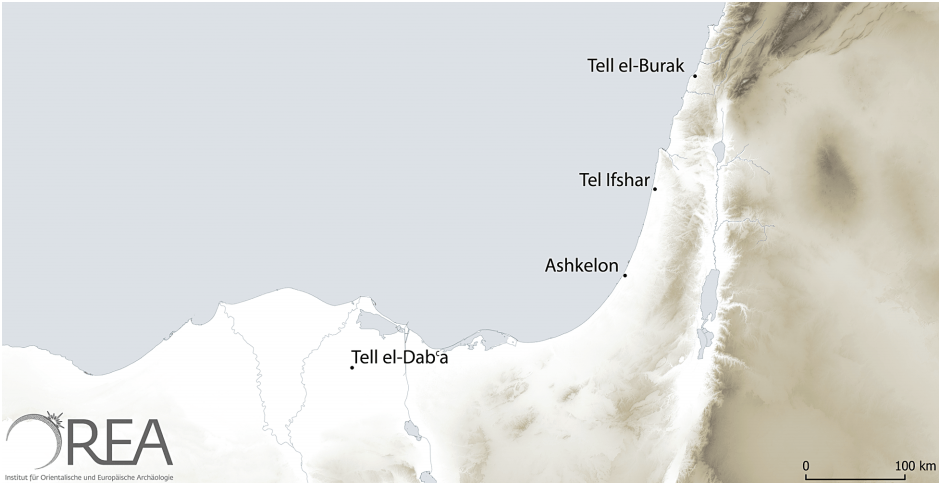

For the past decades, absolute (calendrical) dates for the Middle Bronze Age of the southern and central Levant and its connections with Egypt were hotly debated among archaeologists, Egyptologists, and Biblical scholars. Some researchers, such as William Dever, argued for a high or traditional chronology, that connected the Middle Bronze I period with the 12th Dynasty, the Middle Bronze II with the 13th Dynasty, and the Middle Bronze III with the 15th (or Hyksos) Dynasty. According to this chronological framework, the Middle Bronze I/II transition would fall to c. 1775 BC.

The traditional (high) chronology has been challenged by Manfred Bietak who proposed significant lower calendrical dates for the Middle Bronze Age. Bietak directed the long-term excavations of the Austrian Archaeological Institute Cairo at Tell el-Dab’a, ancient Avaris, the capital of Egypt’s Second Intermediate Period, when northern Egypt was ruled by the Hyksos Dynasty. His excavations revealed a substantial amount of artefacts of Near Eastern provenance and thus, Bietak used the Egyptian historical chronology and the archaeological stratigraphy of Tell el-Dab’a for dating the Middle Bronze Age phases of the southern Levant. According to his (low) chronology, the Middle Bronze I would last until the mid-13th Dynasty, the Middle Bronze II until the mid-15th (Hyksos) Dynasty, and the Middle Bronze III until the early New Kingdom. According to this chronological framework, the Middle Bronze I/II transition would fall to c. 1700 BC, some 75 years later than according to the high chronology.

In recent years, radiocarbon dating has increasingly been used to test the proposed chronologies of the ancient Near East. While scholars from the University of Oxford (Christopher Bronk Ramsey and colleagues) could show that absolute calendrical dates for the Egyptian historical chronology are approximately correct, new radiocarbon sequences from several sites in Egypt and the southern and central Levant now challenge the traditional as well as the low chronological framework.

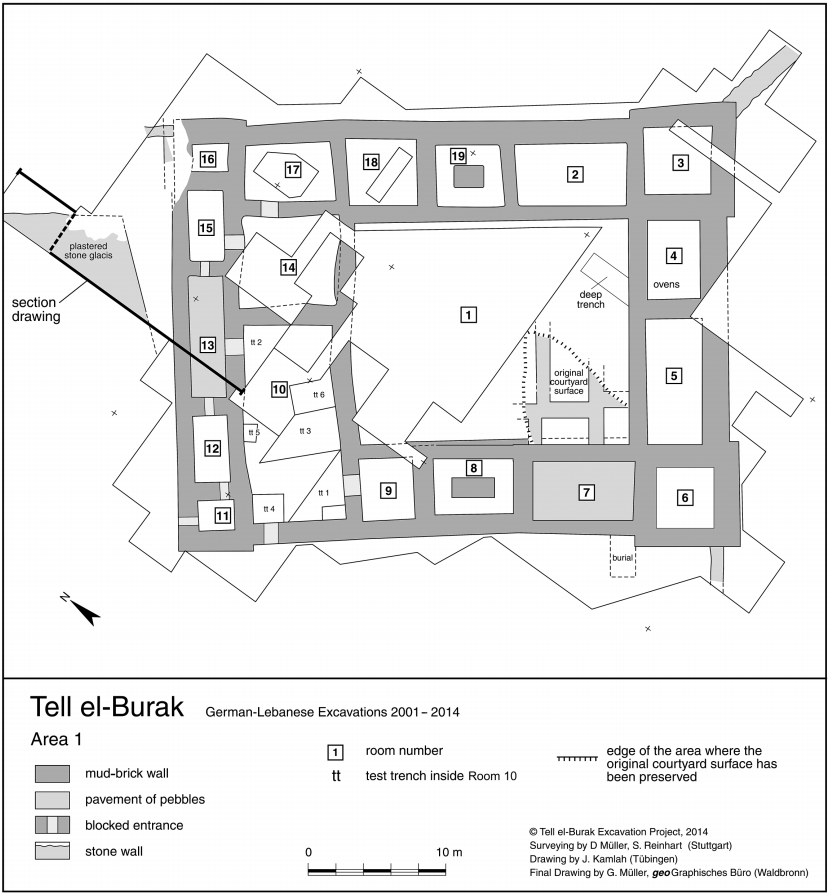

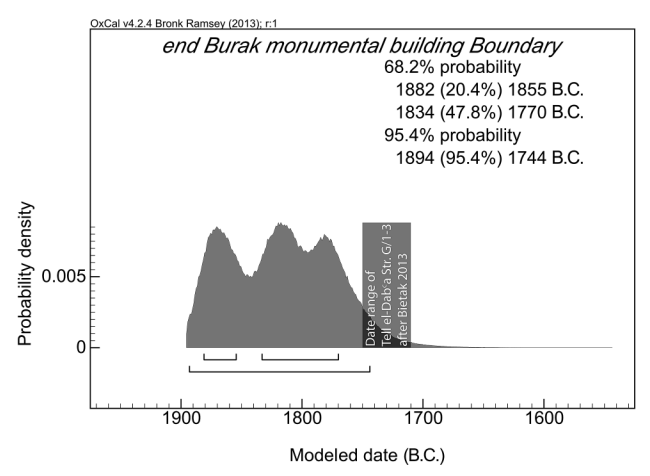

In their current article, Felix Höflmayer and his colleagues present new radiocarbon dating evidence for the Middle Bronze Age site of Tell el-Burak (Lebanon), where a team from the University of Tübingen and the American University of Beirut excavated a monumental mud-brick structure that can be dated to the late Middle Bronze I period. The archaeologists discovered a distinct type of pottery in the layers of the mud-brick building (so-called ridged-neck pithoi) that is also known from the excavations at Tell el-Dab’a and Ashkelon, and according to these excavations, suggested an absolute date in the second half of the 18th century BC.

However, radiocarbon dating of organic samples retrieved from the layers of the mud-brick building provide substantially higher calendrical dates and date the building to the 19th century BC, about 100 years earlier than what could have been expected according to the archaeological parallels at Tell el-Dab’a. But the high dates for Tell el-Burak are not an exception, on the contrary, significantly higher radiocarbon dates have also been produced for the Middle Bronze Age site of Tel Ifshar (modern Israel) and Tell el-Dab’a itself. In fact, all of these sites produced coherent radiocarbon results that challenge the c. 1775 BC or c. 1700 BC date for the transition from Middle Bronze I to Middle Bronze II and suggest a significant higher chronology, where this transition would fall into the 19thcentury BC.

The preliminary results presented in the study challenge the current picture of the Middle Bronze Age eastern Mediterranean and much more data is needed to corroborate the preliminary conclusions outlined in the article by Felix Höflmayer and his colleagues. Future studies will assemble more evidence on this crucial period and once a secure and transparent chronological framework has been achieved, archaeologists, Egyptologists, and Biblical specialists will be able to revise the current narrative of Middle Bronze Age eastern Mediterranean interconnections.

All content provided on this blog is for informational purposes only. The American Schools of Oriental Research (ASOR) makes no representations as to the accuracy or completeness of any information on this blog or found by following any link on this blog. ASOR will not be liable for any errors or omissions in this information. ASOR will not be liable for any losses, injuries, or damages from the display or use of this information. The opinions expressed by Bloggers and those providing comments are theirs alone, and do not reflect the opinions of ASOR or any employee thereof.

WELCOME TO THE ASOR BLOG

WELCOME TO THE ASOR BLOG