Table of Contents for Bulletin of ASOR 379 (May 2018)

You can receive BASOR (and other ASOR publications) through an ASOR Membership. Please e-mail the Membership office if you have any questions.

Pp. 1-18: “The Kingdom of Geshur and the Expansion of Aram-Damascus into the Northern Jordan Valley: Archaeological and Historical Perspectives,” by Omer Sergi and Assaf Kleiman

Fragmented texts in the Hebrew Bible mention a kingdom named Geshur, usually in contexts that denote its independent existence and relations with King David’s royal court (e.g., 2 Sam 3:3; 13:37–38; 14:32; 15:8). Scholars investigating the history of this kingdom have frequently commented on the ambiguous and non-informative

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 19-41: “Late 1st-Millennium B.C.E. Levantine Dog Burials as an Extension of Human Mortuary Behavior,” by Helen Dixon

Simple dog burials, dating primarily to the second half of the 1st millennium B.C.E. (Persian–Hellenistic periods [ca. 6th–1st centuries B.C.E.]), have been excavated at more than a dozen Levantine sites, ranging from a handful of burials to more than 1,000 at Ashkelon. This study systematizes previously discussed canine interments, distinguishing intentional whole burials from other phenomena (e.g., dogs found in refuse pits), and suggests a new interpretation in light of human mortuary practice in the Iron Age II–III-period (ca. 10th–4th centuries B.C.E.) Levant. The buried dogs seem to be individuals from unmanaged populations living within human settlements and not pets or working dogs. Frequent references to dogs in literary and epigraphic Northwest Semitic evidence (including Hebrew, Phoenician, and Punic personal names) indicate a complex, familiar relationship between dogs and humans in the Iron Age Levant, which included positive associations such as loyalty and obedience. At some point in the mid-1st millennium B.C.E., mortuary rites began to be performed by humans for their feral canine “neighbors” in a manner resembling contemporaneous low-energy–expenditure human burials. This behavioral change may represent a shift in the conception of social boundaries in the Achaemenid–Hellenistic-period Levant.

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

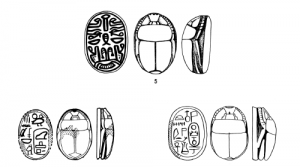

Pp. 43-54: “Evidence for Middle Bronze Age Chronology and Synchronisms in the Levant: A Response to Höflmayer et al. 2016,” by Daphna Ben-Tor

In a recent article published in the Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 375, Felix Höflmayer and his colleagues present a set of radiocarbon data from

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 55-85: “Archaeology and Conservation of the Middle Phrygian Gate Complex at Gordion, Turkey,” by Semih Gönen, Richard F. Liebhart, Naomi F. Miller and Elspeth R. M. Dusinberre

In 2016, a project was undertaken at Gordion, Turkey, to stabilize and conserve the remains of a rubble platform built early in the Middle Phrygian period (ca. 800–700

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

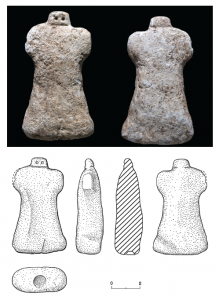

Pp. 87-102: “Human Figurines from the Region of Tel Halif in Light of Schematic Representations in the Chalcolithic Cultures of the Southern Levant,” by Ianir Milevski, Nimrod Getzov and Amir Ganor

This article presents a newly discovered figurine of chalky limestone found at a cave close to Tel Halif in the northern Negev during salvage excavations conducted after

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 103-112: “A Double Abecedary? Halaḥam and ʾAbgad on the TT99 Ostracon,” by Thomas Schneider

This article attempts to advance the debate on the terms inscribed on an ostracon of the Egyptian 18th Dynasty from the excavation of Theban Tomb 99, suggested by Ben Haring to contain the first historical attestation of the Halaḥam sequence. It presents new etymologies for the words listed on the two sides of the document, all of them in Egyptian syllabic writing. The obverse contains at least the five initial consonants of the Halaḥam sequence; the words of the acrostic may form a mnemonic verse. Additionally, the reverse side may provide the first historical attestation of the beginning of the second and historically more consequential ancient alphabet sequence, the ʾAbgad. This sheds important new light on the history of the Semitic alphabets and Egyptian knowledge of alphabetic ordering in the 15th century B.C.E.

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 113-152: “Distancing the Dead: Late Chalcolithic Burials in Large Maze Caves in the Negev Desert, Israel,” by Uri Davidovich, Micka Ullman, Boaz Langford, Amos Frumkin, Dafina Langgut, Naama Yahalom-Mack, Julia Abramov and Nimrod Marom

The Late Chalcolithic of the southern Levant (ca. 4500–3800 b.c.e.) is known for its extensive use of the subterranean sphere for mortuary practices. Numerous natural

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 153-169: “Climate, Settlement History, and Olive Cultivation in the Iron Age Southern Levant,” by Israel Finkelstein and Dafina Langgut

In this article, we suggest a palaeo-climate reconstruction of the Iron Age based on pollen diagrams for sediment cores extracted from the center of the Sea of Galilee and from the Zeʾelim ravine on the western shore of the Dead Sea. We describe three pollen zones that roughly correspond to the Iron Age I, Iron Age IIA, and Iron Age IIB–C. Pollen Zone 1 (ca. 1100–950 b.c.e.) is characterized by high arboreal and olive pollen percentages in both records, representing relatively wet climate conditions and intense olive cultivation in the regions west of the lakes. Pollen Zones 2 (ca. 950–750 b.c.e.) and 3 (ca. 750–550 b.c.e.) are typified by a profound reduction in olive cultivation. Based on Mediterranean tree pollen percentages in the Sea of Galilee record and sediment characteristics in the Zeʾelim profile, climate conditions still seem to have been humid, albeit slightly less than in Pollen Zone 1. The low arboreal pollen in Pollen Zones 2 and 3 in the Zeʾelim diagram is probably the result of intense human influence on the natural vegetation in the Judaean highlands. The lowest olive pollen values during the Bronze and Iron Ages were documented in both records at ca. 700 b.c.e., possibly the outcome of depopulation as a result of deportation and the succeeding abandonment of olive orchards. These and other trends discussed in the article show that climate is only one of the factors that influenced settlement processes and economic trends in antiquity.

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

Pp. 171-195: “Neolithic Kritou Marottou-Ais Giorkis, Cyprus—Living in the Uplands,” by Alan Henri Simmons, Katelyn DiBenedetto and Levi Keach

For many years, the “Neolithic Package” was believed to be a latecomer to the Mediterranean islands. The oldest Neolithic remains were those from the Cypriot aceramic

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

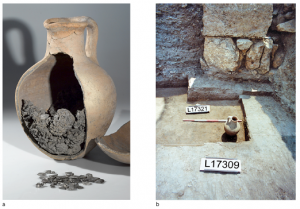

Pp. 197-228: “Four Iron Age Silver Hoards from Southern Phoenicia: From Bundles to Hacksilber,” by Tzilla Eshel, Naama Yahalom-Mack, Sariel Shalev, Ofir Tirosh, Yigal Erel and Ayelet Gilboa

Iron Age silver in the Levant has attracted scholarly attention regarding its function as currency. Scholars debate whether hacksilber can be interpreted as representing a

Click here to access the above article on JSTOR (ASOR membership with online access and/or subscription to JSTOR Current Content required).

To view the entire issue, including book reviews, on JSTOR, click here.