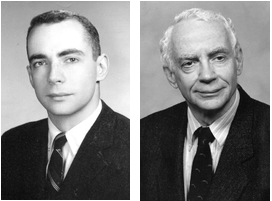

JOHN S. HOLLADAY, JR.: AN APPRECIATION

Timothy P. Harrison

Jack Holladay was a product of the American Midwest, raised in rural Illinois, yet instilled with strong values of cultural diversity and difference, as the son of Presbyterian missionaries called to serve in Thailand and South Asia. Jack’s grounding in the scientific method occurred early in his education, while at the University of Illinois, where he completed a Bachelor of Science in Chemistry/Physics and Zoology. Following graduation, he enlisted in the USAF as a radar observer and flew on all-weather fighter interceptors during the Korean War, a posting he held between 1952 and 1956.

The war would change many things, most notably Jack’s career path. Returning from East Asia, he enrolled at McCormick Theological Seminary in Chicago, earning a Bachelor of Divinity in 1959. It was also at McCormick that Jack first met G. Ernest Wright and was introduced to the exciting developments then taking place in the field of Biblical Archaeology. He followed Wright to Harvard University upon graduating from McCormick, and embarked on a Th.D. under his tutelage at the Harvard Divinity School.

These were formative years, and they set the intellectual framework for the half century of productive scholarship that would follow. The Biblical Archaeology championed by Wright was heavily influenced by the positivist philosophy that dominated the social sciences in American universities during the post-war era. In archaeology, this was expressed through the development of rigorous artifact classification schemes and the reconstruction of ‘culture histories,’ with the aim of identifying broad cultural and social patterns, and ultimately, even the possibility of general ‘laws’ of human cultural behavior. Advances in the natural and physical sciences were also readily adopted and incorporated into the research designs and data collection regimes of archaeological field projects. These innovations found their way into the Shechem Expedition, and with even more enthusiasm, the pioneering Hebrew Union College Expedition to Gezer launched in 1964. However, the Biblical Archaeology advocated by Wright also sought to address historical questions, specifically biblical history, and called for an ambitious approach that involved the analysis of both material culture and textual sources. These converging intellectual trends were deeply influential in giving shape to the research agenda and field methods that would guide Jack’s research over the ensuing decades.

In 1985, following the completion of excavations at Tell el-Maskhuta, Jack’s research endeavors entered a new phase. The next three decades would be devoted to an all-consuming focus on the analysis and synthesis of the rapidly expanding archaeological record for insight into the social and economic institutions of ancient Israel, and in a succession of articles published over the past decade and a half, Jack turned his attention to one of his most abiding interests, the economic foundations of ancient Israelite society. Together, these publications present a richly textured view of the complex economic life of ancient Israel and her neighbors as diminutive nation states navigating for position—and survival—between the great geopolitical powers of the day. Drawing on a wealth of archaeological and textual evidence, Jack highlighted their important role as entrepreneurial agents in the long-distance trade networks and inter-regional economies that fueled the region’s prosperity during the Pax Assyriaca of the late Iron Age.

Perhaps most importantly, though, the exceptional breadth and depth of Jack’s scholarship were matched by a remarkable generosity of spirit. As I experienced in my first encounter, and as his many colleagues and students will attest, Jack exemplified the qualities of the gentleman scholar and teacher: rigorous and uncompromising in his pursuit of knowledge, yet ever generous with associates and nurturing in his mentorship of junior colleagues. This gained more personal meaning for me after I came to Toronto as a newly minted assistant professor. The Near Eastern Studies program in the recently amalgamated Department of Near and Middle Eastern Civilizations was being forcefully downsized at the time through mandatory faculty retirements, of whom Jack was one, in a manner that amounted to an administrative scorched earth policy. Jack provided an ever ready listening ear and much needed counsel during this difficult period of transition as we struggled to keep the program alive, for which I will always be deeply grateful.

Those of us who had the privilege of knowing and working with John S. Holladay, Jr., will be forever the better for it. Jack, may you rest in peace.

* This is an abbreviated version of an appreciation that appeared in Walls of the Prince: Egyptian Interactions with Southwest Asia in Antiquity; Essays in Honour of John S. Holladay, Jr. Leiden: Brill, 2015.