Table of Contents for Near Eastern Archaeology 82.4 (December 2019)

You can receive NEA (and other ASOR publications) through an ASOR Membership. Please e-mail the Membership office if you have any questions.

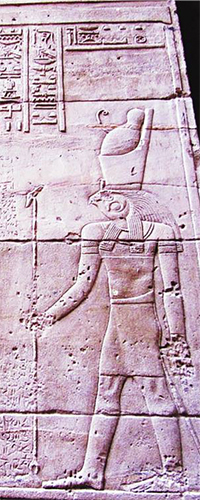

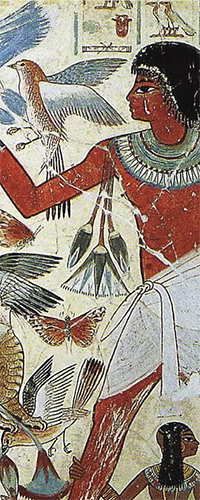

Pp. 200-209: “Milk Libations for Osiris: Nubian Piety at Philae,” by Solange Ashby

During the Roman period, the temples of Philae became a favorite place of pilgrimage for people throughout the Greco-Roman world. Pilgrims came to pray before Isis and her brother-husband Osiris who was buried on the adjacent island of Biga, also known by its Greek name Abaton. Many of these pilgrims left reminders of their pious visits in the form of prayer inscriptions, called proskynemata, which were engraved on the stone walls of the temple complex at Philae. Philae’s numerous temples are located on an island near the first cataract of the Nile, the traditional border between Egypt and Nubia. The Main Temple of Philae, dedicated to the goddess Isis, is oriented toward the south whence come the island’s most consistent visitors: the Nubians. Recovered building blocks and a bark shrine dedicated to Amun indicate that the Kushite king Taharqa was active at Philae during his twenty-six-year reign (690–664 BCE). The last inscriptions of Blemmye priests who traveled to Philae from elsewhere in Nubia were inscribed in 456 CE. Thus, Nubians were active in temple ritual at Philae and the other Egyptian temples of Lower Nubia for a period of more than one thousand years.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 210-215: “Material Evidence of the Early Christian Occupation in the Great Temple of Amun-Ra at Karnak,” by Benjamin Durand

Since 2008, the sector of the Temple of Ptah at Karnak has been subject to an epigraphic, architectural, and archaeological survey (fig. 1). It offers a tremendous opportunity for a diachronic study of the history of occupation in the domain of Amun (Thiers and Zignani 2013). Remains found by Guillaume Charloux in 2015 allow for a closer look at the first occupation of the sector dating back to the Middle Kingdom (Charloux 2017). Likewise, surface structures abandoned at the end of the fourth or middle of the fifth century CE (David 2013, 2017) provide a unique opportunity to gather information about this less-studied period of the area. While in-depth excavation has allowed for a limited peek at the earlier occupation, the surface remains have been cleared and documented in a much more extensive way despite being subjected to long-term human and climatic interference. As a result, all Byzantine remains were excavated as part of the multidisciplinary program conducted in the sector of the Temple of Ptah. The broad extent of the excavation allows for a comprehensive picture, meaning not only a better understanding of the spatial organization of the structures, but also of their function (at least for some of them). Furthermore, the examination of the objects discovered has allowed for the study of the local community and its culture.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

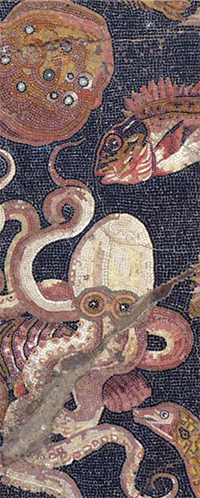

Pp. 216-225: “Bygone Fish: Rediscovering the Red-Sea Parrotfish as a Delicacy of Byzantine Negev Cuisine,” by Gil Gambash, Guy Bar-Oz, Efraim Lev, and Uri Jeremias

In the ancient world, the presence of exotic fish in locations distant from the sea would have signified their importance as luxury foods for social elites. Of special interest in this respect is the Red Sea parrotfish (scarus Sp.), which, while consumed regularly around the Red Sea basin, would have been considered an exotic fish when found at great distances from its point of origin. Recent archaeological excavations in the Negev Desert of the southern Levant have yielded surprising and unprecedented quantities of parrotfish remains, found in the landfills of Byzantine sites located some 200 km from the Red Sea (Tepper et al. 2018; Bar-Oz et al. 2019). These sites (Elusa, Soubeita, Oboda, and Nessana), which date from the fourth through seventh centuries CE, are located along the main system of ancient trade routes that connected the Arabian Peninsula and the Red Sea with the Mediterranean region and Europe (fig. 1). The remains recovered from these sites testify to the historical importance of this fish in Byzantine society and economy, as well as to the development of sophisticated trade networks, which facilitated the supply of Red Sea fish to distant inland locations.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

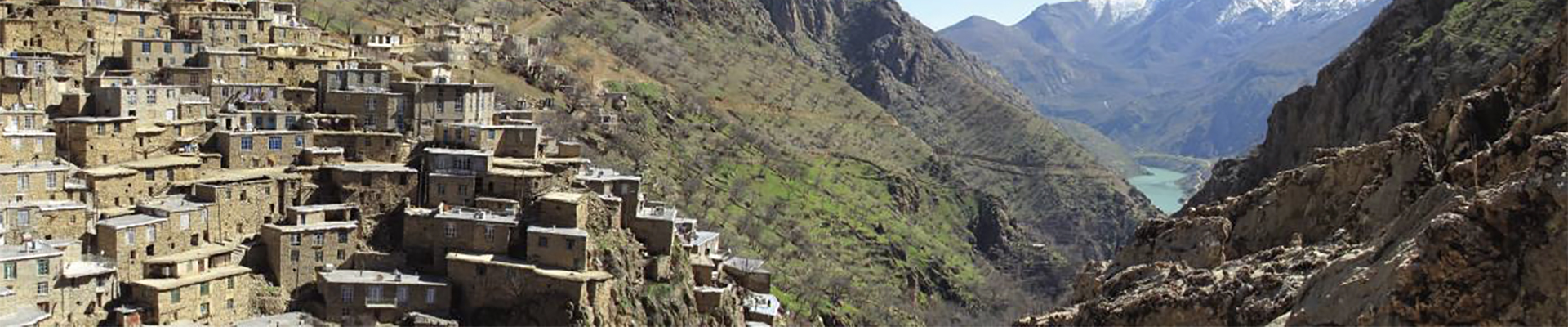

Pp. 226-235: “Rescuing the Paleolithic Heritage of Hawraman, Kurdistan, Iranian Zagros,” by Fereidoun Biglari and Sonia Shidrange

The last two decades have seen a significant development in the field of rescue archaeology in Iran due to the increasing legal protection of archaeological sites in areas that are threatened by rapid urban and rural development. The construction of numerous dams, used for irrigation, hydropower, and other purposes in different parts of the country forced the Iranian Center for Archaeological Research (ICAR) to take action and organize rescue projects. Except for a few projects in the Khuzestan and Fars regions (Wright 1979; Tsuneki and Zeidi 2008), these rescue projects have been focused mainly on excavation of mound sites, which is not surprising given that they are the most common site type in the alluvial plains of Iran. As a result, archaeological salvage projects have predominantly contributed information on late prehistoric and historic periods. The construction of Darian Dam on the Sirwan River in the Central Western Zagros, where archaeological deposits are better preserved in cave and rockshelter contexts, have allowed us to explore such sheltered sites in the framework of a dam salvage project.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 236-247: “Hala Sultan Tekke, Cyprus: A Late Bronze Age Trade Metropolis,” by Peter M. Fischer

The ancient city of Hala Sultan Tekke, which flourished in the Late Bronze Age, that is, from approximately 1650 to 1150 BCE, is situated on the southeastern coast of Cyprus west-southwest of the Larnaca Salt Lake near Larnaca Airport (fig. 1). Today’s salt lake, which is isolated from the open sea, was a protected bay of the Mediterranean in the Late Bronze Age and thus provided convenient anchorage—the basis for trade and the wealth of the city. The city is named after the nearby famous mosque, which has its roots in the seventh century CE. The mosque was built in the area where, according to a local tradition, Umm Haram, a relative or nurse of the prophet Mohammed, died.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.

Pp. 248-255: “Papyrus and the Pharaoh’s Treasure: An Ecological Perspective,” by John Gaudet

Many factors have been cited to explain how and why Egypt developed so quickly in ancient times. The Nile water, the annual inundation with its life-nourishing sediment, the warm climate, and a system of natural barriers to invasion all helped. Other hydraulic civilizations had some or all of these resources, but a unique resource stood out in Egypt. As it happened, that nation was the only one among early hydraulic civilizations in which the giant aquatic sedge papyrus (figs. 1–2) grew and prospered.

ASOR Members with online access: navigate to the token link email sent to you before attempting to read this article. Once you have activated your member token, click here to access the above article on The University of Chicago Press Journals’ website.