PRESERVING NORTHERN IRAQ’S CULTURAL HERITAGE

A Panel Discussion Sponsored by the Smithsonian Institution and the US Department of State

Remarks by Susan Ackerman, ASOR President

Iraq – and especially ancient Iraq – has long been a focus of ASOR’s study. ASOR ran an archaeological research institute in Baghdad from 1923 until we were forced to close for political reasons in 1969, and this institute sponsored multiple excavations in both northern and southern Iraq. It also helped sponsor the Iraq Surface Survey project, which investigated between 1500 and 1800 archaeological sites.

In the 1990’s, following the 1991 Gulf War, ASOR came to express greater awareness about the vulnerability of Middle Eastern archaeological resources. In a 1995 statement, we noted our concerns about the ways in which warfare, the looting of sites, the theft of artifacts, and the illicit trade in antiquities could threaten the archaeological record, and we set forth standards for ourselves to address these dangers. We articulated a commitment that ASOR members would “take every precaution to insure that parts of the archaeological record for which they are responsible are . . . to the extent possible, protected from the eventuality of warfare” and likewise a commitment that ASOR members would “not participate . . . in the buying and selling of artifacts illegally excavated or exported from the country of origin” and that we would “refrain from activities that enhance the commercial value of such artifacts . . . for example, publication, authentication, or exhibition.”

Today, we remain adamant that ASOR publications and its annual meeting will not be used for presentations of such illicit material. An important part of our work today, moreover, includes the ASOR Cultural Heritage Initiatives program, or ASOR CHI, which is dedicated to preserving and protecting the cultural heritage of the Near East and wider Mediterranean and to raising awareness of its degradation.

ASOR CHI came into being in August 2014, when ASOR entered into a cooperative agreement with the US Department of State to document the current condition of cultural heritage sites in Syria and northern Iraq and assess future restoration, preservation, and protection needs. The funding for the first twenty-eight months of this project has recently been supplemented by new monies that will cover the period through March 2018. We are especially pleased that this new funding includes increased support for in-country preservation and restoration projects.

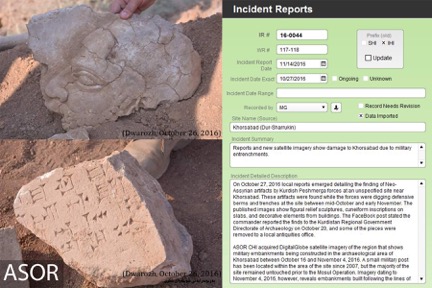

Not surprisingly, though, given the conflict situations that have prevailed in the regions on which ASOR CHI has focused, the initiative’s primary work so far has not been in-country preservation and restoration projects, but intensive monitoring, reporting, and fact-finding regarding the current condition of cultural heritage sites in Syria and northern Iraq. We collect information by using satellite imagery, by searching media sources, including social media, and through in-country informants.

The numbers are staggering. Our inventory of cultural heritage sites in Syria and northern Iraq now includes 13,000 archaeological, religious, and secular sites, as well as museums, libraries, and historic districts. We have conducted 9000 satellite assessments of sites in this inventory, completed 750 detailed condition assessments, made 4150 heritage observations, and compiled and archived 10,000 media entries on cultural heritage incidents and assets. These voluminous data have allowed us to estimate that, at a minimum, 1300 cultural heritage sites in Syria and northern Iraq have sustained damage since the start of our work in August 2014, with 915 of these incidents occurring in the fifteen-month period between September 2015 and December 2016. The damage is overwhelmingly due to intentional destruction and military explosives – and this is especially true in northern Iraq.

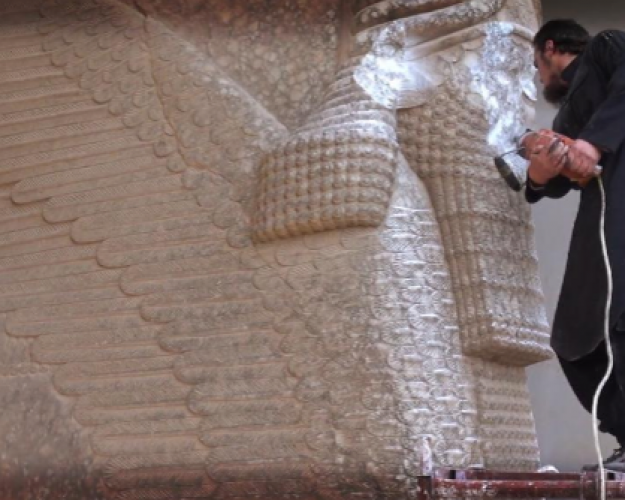

Particularly of concern in northern Iraq is the so-called Islamic State’s targeting of Islamic heritage and ancient Mesopotamian, Hellenistic, and Roman-era sites for destruction and also theft. All of us probably carry in our heads images of ISIS’s intentional destruction of the ancient Mesopotamian palace at Nimrud and probably also carry in our heads images of ISIS’s intentional destruction of Mesopotamian, Hellenistic, and Roman-era antiquities at the Mosul Museum and of the destruction of remains from the ancient Mesopotamian capital city of Nineveh. ASOR CHI has also been able to help US authorities document a pattern of theft, whereby ISIS – by issuing looting permits in the territories it controls and by imposing a 20% tax on antiquities traders – facilitates the plundering of archeological sites and then supports itself with the proceeds (estimated in a recent Wall Street Journal report to be in the range of $88 million/year).

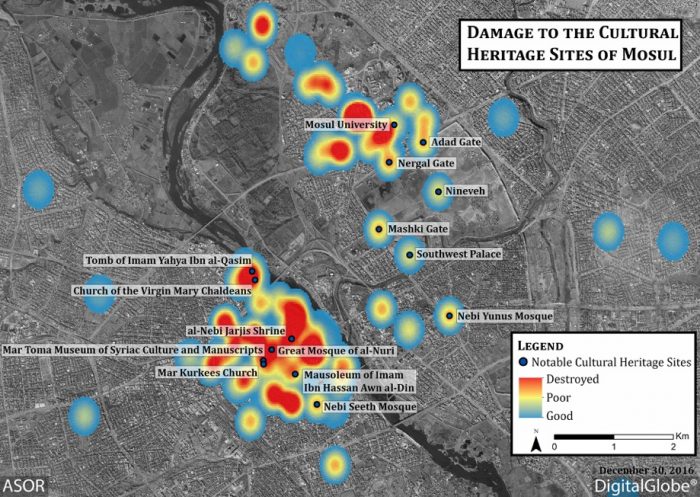

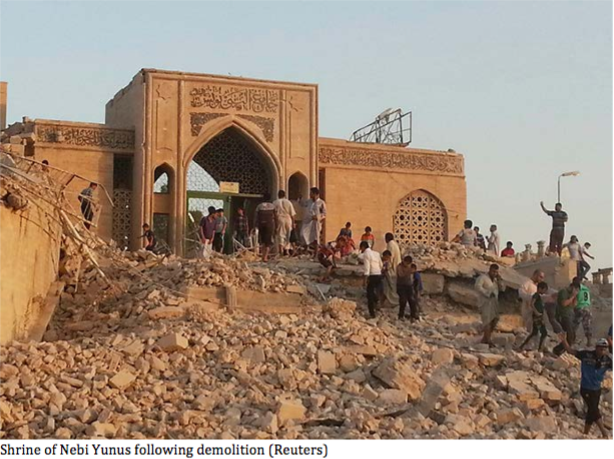

But while western media has tended to focus on these attacks that plunder and destroy ancient heritage, it is important that we realize that increasingly, ISIS’s destructive acts have been directed toward late antique, medieval, early modern, and even more modern religious sites. Indeed, on a map ASOR CHI has produced showing damage to cultural heritage sites in Mosul, all but one of the sites marked as damaged in the southern half of the city is a religious site that, at the time of its incurring damage, was still in use by a modern community of faith. These sites include Christian churches and Islamic shrines, tombs, and mausoleums considered heretical according to ISIS ideology – for example, the shrine of Nebi Yunus, or the Prophet Jonah, which was destroyed by ISIS in July 2014. These destructions serve primarily to advance the ISIS policy of cultural cleansing and the erasure of Iraq’s rich cultural diversity.

It’s all been just mind-bogglingly depressing. But let me end on a hopeful note, by telling you of an ASOR CHI project that is just beginning, through a grant funded by the Whiting Foundation. This funding supports digital preservation of textual collections housed in Mosul, including Islamic manuscripts, cuneiform tablets, and architectural and monumental inscriptions. At ASOR, we are extremely gratified to be able to undertake this work of preservation instead of focusing so extensively on documenting destruction; we are also extremely gratified that the Whiting funding will pay to train local heritage professionals to do the digitization work. We thereby preserve not only a particularly precious part of Mosul’s intellectual and cultural legacy, but also we also support the empowerment and enhanced financial well-being of ASOR’s members, colleagues, and friends in northern Iraq. We demonstrate, finally, the power of public-private partnerships, as our Department of State cooperative agreement and the capacity we have built in order to fulfill that agreement’s terms have helped us attract private funding dedicated to protecting northern Iraq’s rich cultural heritage.