December 2019

Vol. 7, No. 12

What Did Jesus Look Like?

By Joan E. Taylor

Everyone knows what Jesus looks like: he is the most painted figure in all of western art, recognized everywhere as having long hair and a beard, a long robe with sleeves (often white) and a mantle (often blue).

But what did he really look like, as a man living in Judaea in the 1st century? This subject has long been of interest. I have already written on John the Baptist and his clothing, but not about Jesus. Nevertheless, over the years, numerous television documentaries have asked me for guidance on dramatizing aspects of ancient life. In order to give them clear directions, I gathered information about what Jesus looked like, or rather, what he is said to have worn. I would like to share this here.

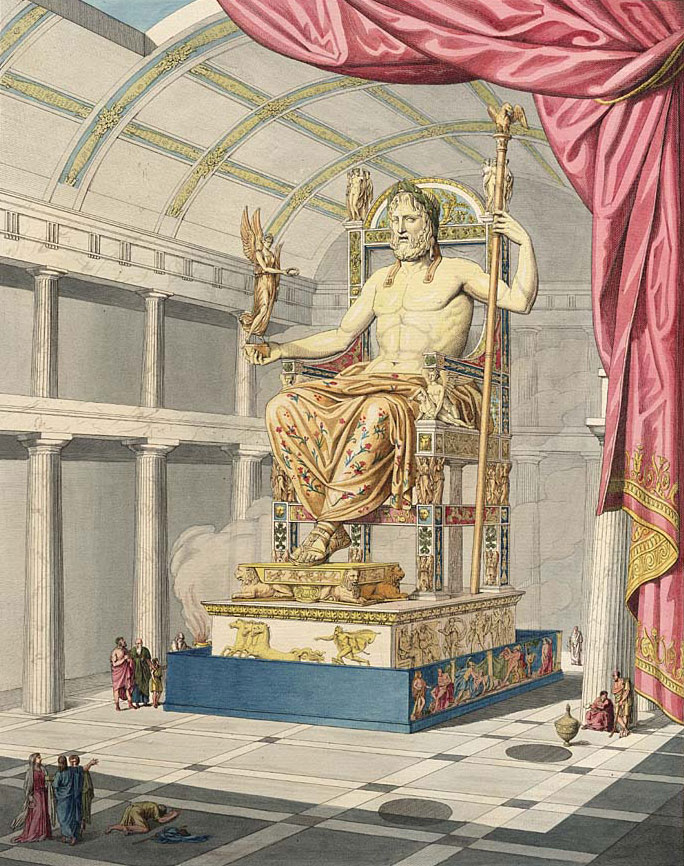

It is worth emphasizing that images of Jesus over time give us clues on how Jesus was imagined in different environments, but say absolutely nothing about what he really looked like. Our images of Jesus were largely created in the Byzantine era (4th-6th centuries). Byzantine images of Jesus were based on the image of a Graeco-Roman deity, for example the famous statue of Olympian Zeus by Phidias in the 4th century BCE.

Zeus in Olympia, by Antoine Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy. (1755-1849) (Wikimedia Commons)

Zeus in Olympia, by Antoine Chrysostome Quatremère de Quincy. (1755-1849) (Wikimedia Commons)

This huge statue was located inside the Temple of Zeus at Olympia in Greece and depicted a long-haired and bearded Zeus on a throne. It was so well-known that the Roman Emperor Augustus had a copy of himself made in the same style, but without the godly long hair and beard. Men in the 1st century rarely had long hair; it was considered either godly or girlie.

Portrait of Augustus created ca. 20–30 BC; the head does not belong to the statue, dated middle 2nd century CE. (Wikimedia Commons)

Portrait of Augustus created ca. 20–30 BC; the head does not belong to the statue, dated middle 2nd century CE. (Wikimedia Commons)

Byzantine artists, looking for iconography that emphasized Jesus’s heavenly rule as cosmic King, drew on such depictions of a deity sitting on a throne – representing his authority over the earth and his coming role as judge. We also then get the godly long hair and beard, because Jesus is like a younger version of Zeus/Jupiter, Neptune or Serapis, just as God as ‘Father’ would in due course be depicted as an older (white-haired) version of the same gods.

As time went on the sun god’s halo was also added to Jesus’s head to show his heavenly nature. The winged victory in the hands of Olympian Zeus was replaced with gesture of blessing, with the Bible held in Jesus’s hand instead of a spear. This iconography of Jesus with long hair, a beard and a halo comes from the 4th century onwards, with Jesus sitting on a heavenly throne, like Olympian Zeus, as cosmic judge of the world: the Alpha and Omega, beginning and end (Revelation 21:5-6, and 22:13). With this in mind we can ‘read’ the apse mosaic from Santa Pudenziana, Rome, dated to the early 5th century CE.

Apsis mosaic of Santa Pudenziana. (Wikimedia Commons)

Apsis mosaic of Santa Pudenziana. (Wikimedia Commons)

Everything here, from the long golden robe to the long hair and beard, has meaning. The point is not to show Jesus as a man of 1st-century Judaea, but to make theological points about Jesus as Christ (King) and divine Son. In this classic Byzantine Jesus, the ‘mini-Zeus’ version, the long robe with baggy sleeves indicates status. By the Byzantine era, royal, ecclesiastical and elite males wore such long robes as seen in depictions of the emperor Justinian and his entourage in the Church of San Vitale in Ravenna.

Court of Emperor Justinian with (right) archbishop Maximian and (left) court officials and Praetorian Guards; Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy. (Wikimedia Commons)

Court of Emperor Justinian with (right) archbishop Maximian and (left) court officials and Praetorian Guards; Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna, Italy. (Wikimedia Commons)

But at the time of Jesus long tunics were usually worn by women, not men. There were exceptions. For a man to wear a stolē, a longer garment, could also indicate high status at this time (e.g. Mark 12: 38; Luke 20: 46) or heavenly raiment (Mark 16: 5; Rev. 6: 11; 7: 9, 13, 14). But Jesus scorned men who advertised their status by wearing these (Mark 12: 38; Luke 20: 46). It is so ironic then that he is often depicted as wearing a longer garment himself.

The earliest extant images of Jesus in Roman catacomb paintings show him as a teacher/philosopher or magus (wonder-worker, with a wand), dressed in the common clothing of the time for a man: a knee length (essentially sleeveless) tunic (chitōn) and a long mantle (himation). He is also beardless and short-haired. We see this in the depiction of Jesus healing a woman with an issue of blood (Mark 5:25-34) in the late 3rd century Catacomb of Peter and Marcellinus.

The healing of a bleeding woman, Rome, Catacombs of Marcellinus and Peter. (Wikimedia Commons)

The healing of a bleeding woman, Rome, Catacombs of Marcellinus and Peter. (Wikimedia Commons)

Jesus was recognizable in these portrayals not because of how he looked but by what he did. The Gospel stories were so familiar to the viewers that they recognized Jesus from what was being shown. Still, for people today, this image of Jesus seems strange. When a picture of Jesus was discovered last year on a 4th/5th century glass paten (Eucharist plate) found in southern Spain, one of the things the media was most interested in was that Jesus was beardless.

Beardless Jesus, Spain. (Huffington Post)

Beardless Jesus, Spain. (Huffington Post)

Did Jesus actually have a beard? As a kind of wandering sage, I think he would have had one, simply because he did not go to barbers. This was also the common appearance of a philosopher; the Stoic philosopher Epictetus considered it appropriately natural. He did not have a beard just because he was a Jew. A beard was not distinctive of Jews in antiquity. While by the time the Babylonian Talmud was written in the 5th-6th centuries beardedness might have been common for Jewish men (b.Shabbat 152a, ‘The glory of a face is its beard’), it was never identified as an indicator of Jews in the 1st century. In fact, one of the problems for oppressors of Jews in the Diaspora was identifying them when they looked like everyone else. However, the Jewish men on Judaea capta coins (issued by Rome after the capture of Jerusalem in 70 CE) are bearded but with short hair; this is probably how Romans imagined Jewish men in Judaea, even if in the Diaspora a Jewish man may have looked like every other guy.

Judaea capta coin. (Wikimedia Commons)

Judaea capta coin. (Wikimedia Commons)

So what did Jesus really look like? Jesus wore normal clothing, unlike John the Baptist; John’s clothing was sufficiently unusual and Elijah-like to be mentioned (Mark 1:6: “And John was wearing camel hair and a skin girdle around his waist.”) So what was normal for men of 1st-century Judaea?

Important insights into dress and appearance are gained by studies of the Egyptian mummy portraits from the 1st century BCE to the 3rd century CE. These portraits depict a style of clothing and hair that was probably universal in the eastern Mediterranean, including in the region of Judaea. This is also clear from the archaeological discoveries of Masada and the Judaean Desert Caves. The clothing of rich people was mainly distinguished by expensive dyes and fineness of the cloth, but the actual styles were quite similar.

Most men wore a simple short tunic (chitōn), finishing around the knees, as Jesus is depicted wearing in catacomb art. Men were supposed to be ready for action – movement – so they did not usually have long robes; the high status longer garment sometimes worn by the elite advertized leisure. To be really active you would ‘gird your loins’ by tucking your chitōn up by pulling it through your legs and tying it.

A chitōn invariably had two bands of color that ran from the shoulder to the hem, front and back. These are seen in many examples from excavations in sites close to the Dead Sea, where textiles have been well preserved, especially from Nahal Hever and Masada.

On top of the tunic a man would wear a himation or mantle, a large piece of colored woolen material. A woman who wanted to be healed touched Jesus’s himation (Mark 5:27). There was also a type of fine linen mantle/wrap called a sindōn, but Jesus only wore one of these in death (Mark 15:46).

Jesus did not wear white. This color was distinctive, requiring bleaching, and in Judaea it was associated with the Essenes (Josephus, War 2:123), a legal school of Judaism who followed a strict interpretation of the law and a life of community and extreme purity. It is also associated with heavenly attire (Mark 16:5; Rev. 19:14). The difference between Jesus’ regular clothing and bright, white clothing is described specifically during the Transfiguration scene where we are told that Jesus’ clothing (here himatia) became ‘glistening, intensely white, as no fuller on earth could bleach them’ (Mark 9.3). He is thus transformed into wearing the shining garb of angels.

Jesus would probably have worn un-dyed wool for his tunic and a dyed mantle. It is clear from clothing found in Masada and the caves by the Dead Sea that clothing was often very highly colored. The ordinary people of Jesus’ time loved color, and their clothing has beautiful shades of red, green, and types of purple designed to imitate the colors favoured by the wealthy. Their cloth was durable, and they did not wear earthy hues but vibrant ones, especially for their himatia.

Textile fragment from Masada. (Wikimedia Commons)

Textile fragment from Masada. (Wikimedia Commons)

Textile fragment from Masada. (Wikimedia Commons)

Textile fragment from Masada. (Wikimedia Commons)

We are told additionally about Jesus’s clothing during his execution, when it is divided among soldiers (Mark 15:24; Matt. 27:35; Luke 23:34; John 19:23-24). Jesus is said in the Gospel of John (19:23-24) to have worn a chitōn (tunic) and himatia (mantles), plural. The soldiers did not want to rip his chitōn, since it was made as one piece of cloth. It could not be separated out into pieces as was sometimes the case, so they cast lots for which soldier would take it. This is curious because one person described as wearing a seamless garment is the high priest (Josephus, Ant. 3:161). Was John trying to make some hidden allusion to the high priest? Or was he simply recording a peculiarity of Jesus’s tunic? I favor the latter, because in this Gospel Jesus’s clothing is very carefully described.

The Roman soldiers divided Jesus’s mantles (himatia) into four shares (John 19:23), indicating that he was wearing two mantles each made of two pieces of cloth that could be separated. This is especially interesting. One of the himatia was probably a tallith or prayer shawl. This was traditionally made of undyed creamy-colored woollen material with blue-striped edges and fringes, which would be drawn over the head when praying. While there were no fringed mantles found in the caves by the Dead Sea, there was blue wool with fringes (tzitzith), possibly used to make them.

Since talliths are defined as distinctive clothing for Jewish men, worn either singly or with another mantle for warmth, there seems no reason to doubt that Jesus wore one. Indications that Jesus wore a regular mantle as well as the tallith mantle are found not only at the crucifixion scene but also on another occasion: Jesus takes off his mantles, himatia, when he washes the feet of his disciples (John 13:4, 12). Here there is a distinction made between the mantles he took off and the tunic he kept on. The Gospel of John, therefore, provides a specific indication of what Jesus wore which correlates with the presentation of the night of Passover eve as cold (John 18:18, 25, cf. Mark 14:24). Jesus would have worn a mantle for warmth along with a distinctively Jewish tallith, as other Jewish men would have worn in cold weather. In wearing two mantles, one of which was a tallith, Jesus’s clothing would have identified him as a Jew like any other.

On his feet? Jesus would have worn sandals. In the desert caves close to the Dead Sea and Masada sandals from the time of Jesus have come to light. They were very simple, with the soles of thick pieces of leather sewn together, and the upper parts made of straps of leather going through the toes.

Sandals from Masada. (The Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

Sandals from Masada. (The Institute of Archaeology, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

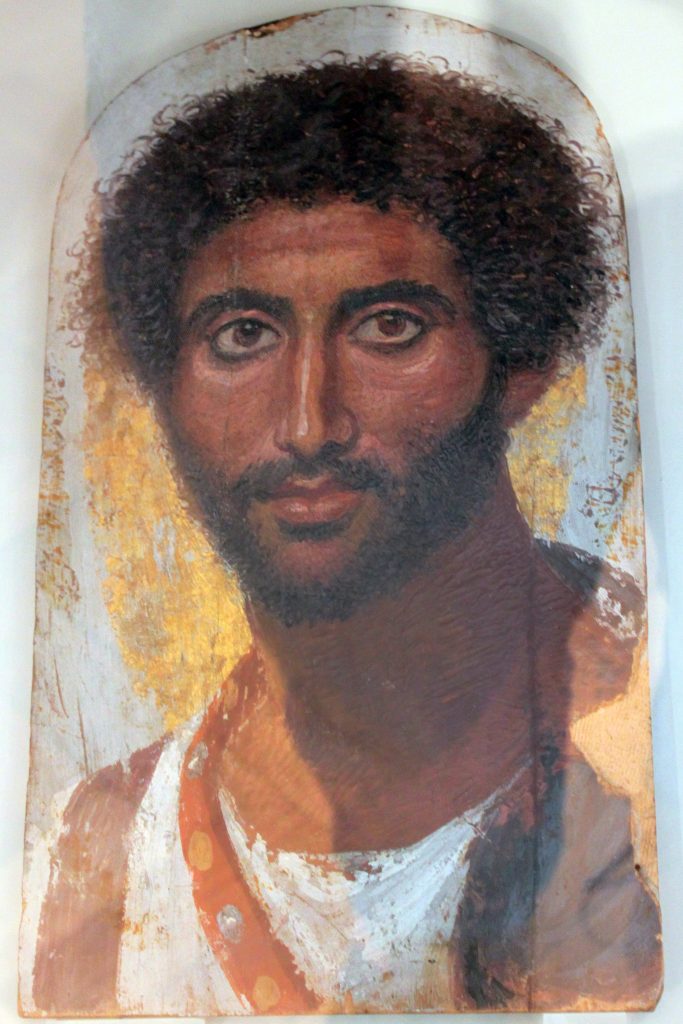

And what about Jesus’s face? In the mummy portraits, the people were Greek-Egyptian, but there was a large Jewish population also in Egypt and some ethnic mixing. Their faces, so realistic, are the closest we have to photographs of the people of Jesus’s own time and place.

Mummy Portrait of a young officer with sword belt, Berlin. (Wikimedia Commons)

Mummy Portrait of a young officer with sword belt, Berlin. (Wikimedia Commons)

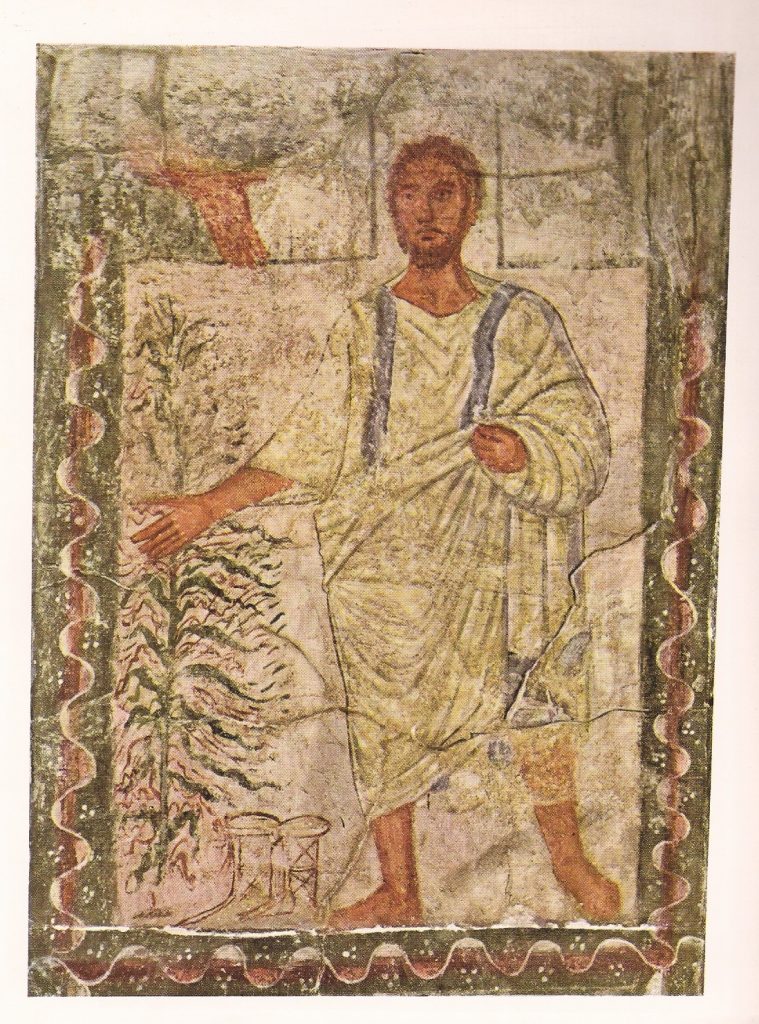

If we are to imagine Jesus then, as a Jew of his time, the mummy paintings provide a good clue to his appearance. However, there is one other place to look: to the synagogue Dura Europos, dating from the early 3rd century. The depiction of Moses on the walls of the synagogue of Dura-Europos is probably the closest fit, I think, since it shows how a Jewish sage was imagined in the Graeco-Roman world. Moses is shown in undyed clothing, appropriate to tastes of ascetic masculinity (eschewing color), and his one mantle is a tallith, since one can see tassels (tzitzith). This image is a far more correct as a basis for imagining the historical Jesus than the adaptations of the Byzantine Jesus that have become standard.

Moses and the burning bush, Dura Europos synagogue wall painting. (Wikimedia Commons)

Moses and the burning bush, Dura Europos synagogue wall painting. (Wikimedia Commons)

Joan Taylor is Professor of Christian Origins and Second Temple Judaism at King’s College London.

Apsis mosaic of Santa Pudenziana. (Wikimedia Commons)

Apsis mosaic of Santa Pudenziana. (Wikimedia Commons)