November 2019

Vol. 7, No. 11

Judeans and Goddesses at Elephantine

By Collin Cornell

“Elephantine” is an English adjective describing monumental size—“like an elephant.” It is also the proper name for an island in the Nile River, whose shape supposedly resembles an elephant. This island, measuring less than half a square kilometer (or 118 acres), was the site of an ancient fortress that guarded the southern border of Egypt.

Map showing location of Elephantine. (http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-3589153/It-paid-royal-servant-Ancient-Egypt-Stunning-tombs-pharaohs-butlers-opened-following-restoration-elaborate-paintings.html)

Map showing location of Elephantine. (http://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-3589153/It-paid-royal-servant-Ancient-Egypt-Stunning-tombs-pharaohs-butlers-opened-following-restoration-elaborate-paintings.html)

Aerial view of Elephantine today. (https://static0.traveltek.net/uploaded/2015/10/1445000606.JPG)

Aerial view of Elephantine today. (https://static0.traveltek.net/uploaded/2015/10/1445000606.JPG)

During the late sixth and fifth centuries BCE (525-404 BCE), the Persian Empire occupied Egypt. They also took over management of the island fortress on Elephantine. Instead of replacing the garrison with Persian soldiers, the Empire decided to keep the mercenary force that had already been there on payroll. These troops included a variety of peoples—Greeks and central Asians, but mostly Aramaic-speakers from Syria and Judea.

The latter community of Judeans maintained a temple to their god, YHW, on the island. This fact alone has made them particularly interesting to scholars of Israelite religion and early Judaism. What does it mean that Judeans who were contemporaries of the biblical Ezra and Nehemiah had their own temple for YHW—in seeming violation of the Pentateuch’s laws that limit the worship of YHWH to one place? Did they just not know about the Pentateuch, and if so, what would that entail for its development and ascendancy?

Passover letter. (http://cojs.org/wp-content/uploads/2008/04/Passover_Letter_Front.jpg)

Passover letter. (http://cojs.org/wp-content/uploads/2008/04/Passover_Letter_Front.jpg)

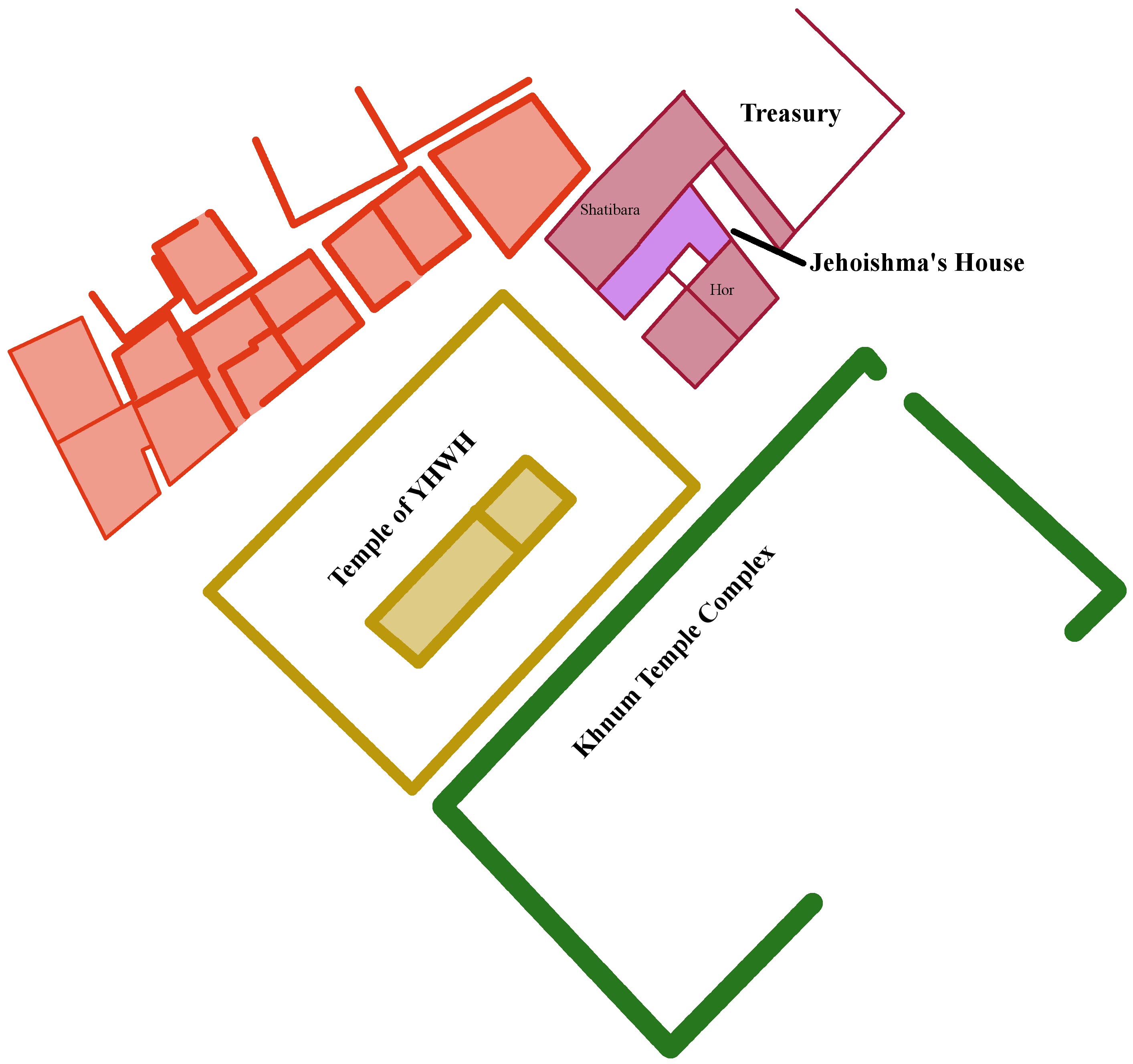

Map of Elephantine temples. (https://gatesofnineveh.files.wordpress.com/2015/01/elephantine.jpg)

Map of Elephantine temples. (https://gatesofnineveh.files.wordpress.com/2015/01/elephantine.jpg)

Even more intriguing are clues left in the Aramaic writings that have survived from this Judean military unit: possible allusions to a goddess named Anat. One administrative document lists contributions of silver given to the YHW temple, but it also indicates that some of the moneys received were dedicated to “Anat-bethel.” Another document, a court record from a dispute over the ownership of a donkey, shows that a Judean man swore an affidavit by “Anat-YHW.”

If the Judeans on Elephantine worshipped a goddess like Anat alongside YHW, this would raise important questions about the profile of early Judaism. Was this kind of religious practice—which the Hebrew Bible condemns—widespread, or even commonplace, among Judeans of this era? How would this reality affect our understanding of the Bible’s emergence as the religious norm for Judaism? After more than a century of academic discussion about the texts from Elephantine, there is little consensus about the presence or significance of goddess veneration by Judeans living there.

What scholarly investigations of the goddess have not examined are non-textual data from Elephantine. The same excavations that found Aramaic papyri also uncovered a number of figurines. Some of them, hewn rather roughly from wood, picture a grotesque dwarf-god. Others made by placing clay into a mold feature a naked woman lying on a bed. One of these clay objects, a plaque, shows a naked woman standing between two pillars, with a smaller child by her side.

Plaque figurine, British Museum E16026. (https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=315001&partId=1&searchText=1885,1010.29&page=1)

Plaque figurine, British Museum E16026. (https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details.aspx?objectId=315001&partId=1&searchText=1885,1010.29&page=1)

Plaque figurine, AN1292122001001, © Ashmolean Museum, University of Oxford. Photography by British Museum staff. (https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/publications/online_research_catalogues/catalogue_image.aspx?objectId=3444805&partId=1&searchText=DC.*&orig=/research/publications/online_research_catalogues/russian_icons/catalogue_of_russian_icons.aspx&sortBy=catNumber&numPages=12¤tPage=6&catalogueOnly=True&catparentPageId=35374&output=bibliography/!!/OR/!!/8909/!//!/Naukratis:+Greeks+in+Egypt/!//!!//!!!/&asset_id=1292122001)

Naked female figure standing in niche or shrine, British Museum EA68861. (https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?assetId=1469097001&objectId=123468&partId=1)

With few exceptions, scholarship on the religion of Elephantine Judeans has forgotten about these female figurines. In concert with other, more recent discoveries, however, these objects offer a fresh vantage point into the matter of the Judean goddess. Archaeologists have found numerous other examples of terracotta plaques embossed with the motif of a woman standing between pillars. These pillars are usually understood as columns at the entrance of a temple. Indeed, one such plaque was recovered from the interior of a Philistine temple in Gaza—the very same temple, apparently, that the bas-relief pillars and architrave on the plaque represent in miniature. Many more plaques with similar design originated in Egypt during the same time period when Judeans staffed the island fortress. Egyptologists commonly interpret the woman on such plaques, sometimes with a child beside her as on the Elephantine exemplar, as a goddess. The temple façade within which she stands may evoke an actual, real-life shrine in her honor.

These findings are suggestive with regard to the Judeans of Elephantine. A shrine plaque unearthed from their living quarters on the island images a woman, likely a goddess, inside of a temple, which may recollect an identifiable, local temple. But this evidence is circumstantial at best; no definite connection can be drawn between this terracotta artifact and the Judeans in particular, since they made their home in a multicultural mercenary community. Perhaps this plaque belonged to a Phoenician merchant who took up temporary residence on the island, or to an Aramean comrade-in-arms.

But another line of inquiry reshapes the issue of the object’s proprietorship. In several Aramaic legal texts, the Dutch scholar Bob Becking observes that inhabitants of the fortress accept oaths taken in the name of someone else’s god. For example: one document, a divorce proceeding, splits assets between the ex-wife, a Judean woman, and her ex-husband, an Egyptian. The Judean ex-wife takes an oath that some of their properties are hers—but, notably, she swears by her ex-husband’s deity, the local goddess named Sati. Some have taken this as an indication that the she has “converted” to her husband’s religion, or that her religious practice is “syncretistic.”

But Becking denies these categories. Instead, the Judean woman respects that the name of the Egyptian goddess taps into real divine power, which could threaten her if she reneges on her oath. Similarly, another court proceeding addresses a property dispute between two men, one a Judean and the other a central Asian. The Judean takes an oath in the name of YHW—and the central Asian accepts it as binding. Although YHW was not his god, he believed that this name actually invoked the divine realm. Similarly, even if a Phoenician or an Aramean made or used the shrine plaque, Becking’s argument would mean that their Judean neighbors would likely have recognized this object—and other figurines—as a true point of access to divine power and blessing.

In the end, then, the forgotten figurines do not resolve the question of goddess worship among the Judeans of Elephantine, let alone in early Judaism more broadly. But they do show that Judeans lived cheek-by-jowl with clay images of a goddess. Taken together with the textual data—allusions to Anat by Judeans, not to mention a biblical text like Jeremiah 44, which condemns Judeans resident in Egypt for venerating the Queen of Heaven—this fact increases the probability that Judeans revered a goddess. But even if they did not, their colleagues on the island did—and the Judeans likely believed in her divine power.

Collin Cornell is visiting assistant professor for the School of Theology at Sewanee: The University of the South.