October 2018

Vol. VI, No. 10

Comics, Narrative and the Archaeology of the Ancient Near East

By John Swogger

Archaeologists have always embraced new ways of visually recording and representing the past and the work that they do. In the nineteenth and early-twentieth century, photography was enthusiastically adopted by archaeologists not only as a way of recording excavations and documenting sites, but also as a way of giving public audiences a better idea of what their work entailed.

Sir Flinders Petrie with his camera. (Petrie Museum archive PMF/WFP1/115/5/2)

Sir Flinders Petrie with his camera. (Petrie Museum archive PMF/WFP1/115/5/2)

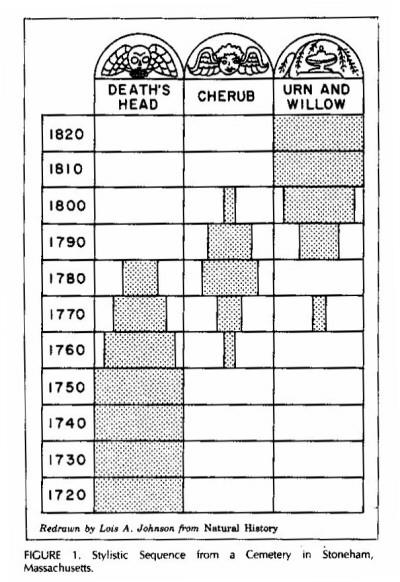

In the middle of the twentieth-century, greater access to x-rays, aerial photography and microscopic photography changed once again the way in which archaeological work and the past was represented. Developments in scientific and statistical analysis of artefacts, soil samples and radiocarbon dates similarly resulted in new ways of viewing the past: through charts, graphs and histograms.

A ‘battleship curve’ of frequency distribution. (http://www.histarch.illinois.edu/plymouth/deathsheadfg1.html)

A ‘battleship curve’ of frequency distribution. (http://www.histarch.illinois.edu/plymouth/deathsheadfg1.html)

Throughout the history of the discipline, various forms of representational media have given greater visibility to the archaeological profession as well as to archaeological research.

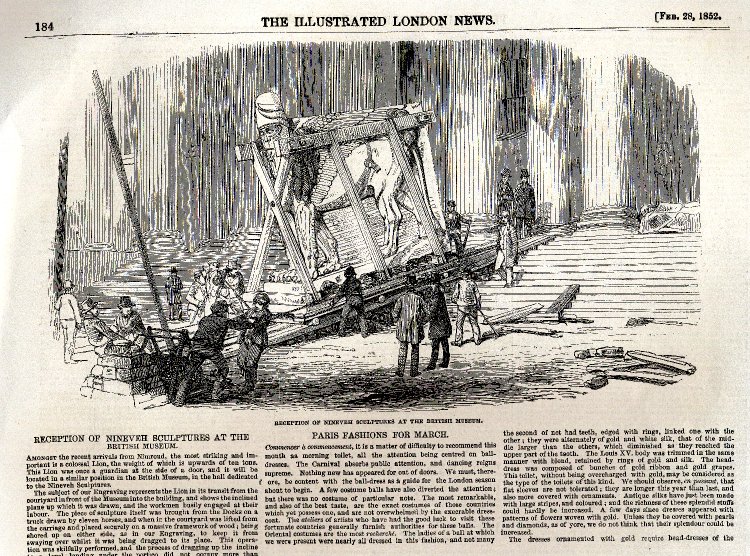

A new medium now also being used for the same reasons are comics. For most people, the term “comics” conjures up images of talking animals or superheroes in capes. But “comics” simply describes a very specific form of illustration in which image and text are closely inter-related. Comics and other forms of graphic narrative have been used for decades to tell non-fiction stories, too. In archaeology, this stretches back, arguably, to nineteenth-century reporting in the Illustrated London News.

Reception of Nineveh sculptures at the British Museum, Illustrated London News, 1852. (http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?assetId=1285510001&objectId=3498943&partId=1)

Reception of Nineveh sculptures at the British Museum, Illustrated London News, 1852. (http://www.britishmuseum.org/research/collection_online/collection_object_details/collection_image_gallery.aspx?assetId=1285510001&objectId=3498943&partId=1)

In the United States, non-fiction newspaper comic strips were used as early as 1926 to tell the history of the state of Texas. In Europe, factual comics were used from the 1960s to teach younger audiences about history and archaeology, through popular educational publications like the Look and Learn magazine.

The ability of comics to closely interrelate image and text within a coherent narrative makes them ideal for introducing an audience to an unfamiliar subject. The combination of explanation and visual context can convey significant amounts of information in an easy-to-digest format, meaning a comic can unpick a complex subject without “dumbing it down”.

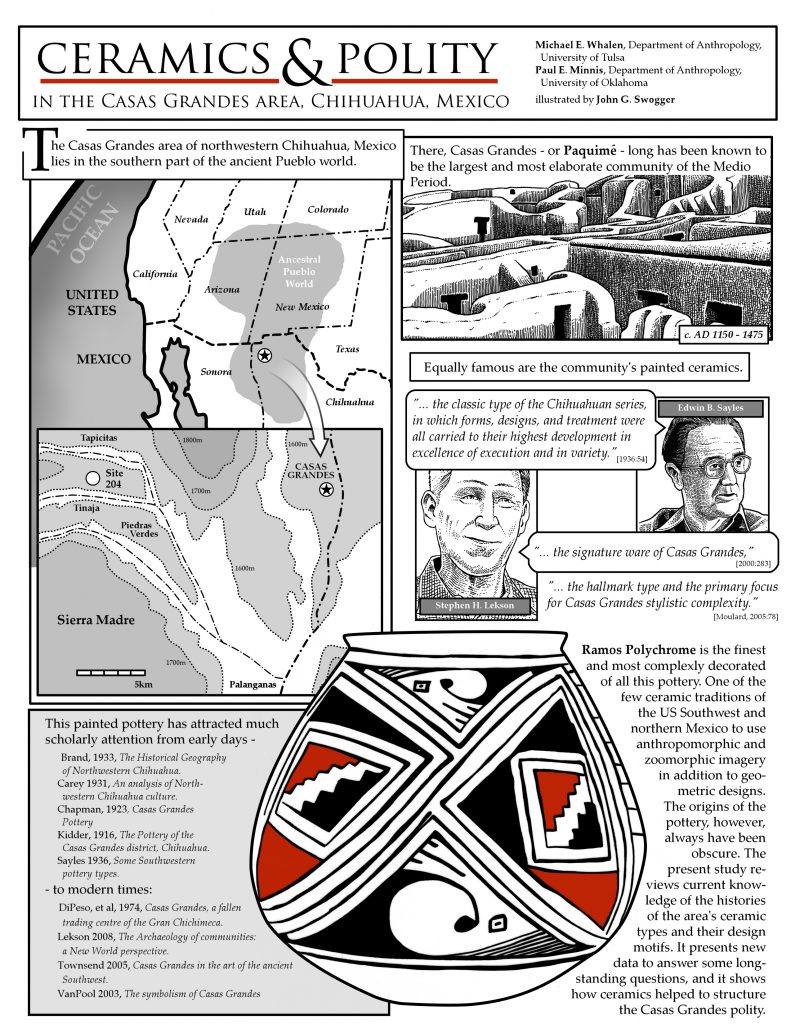

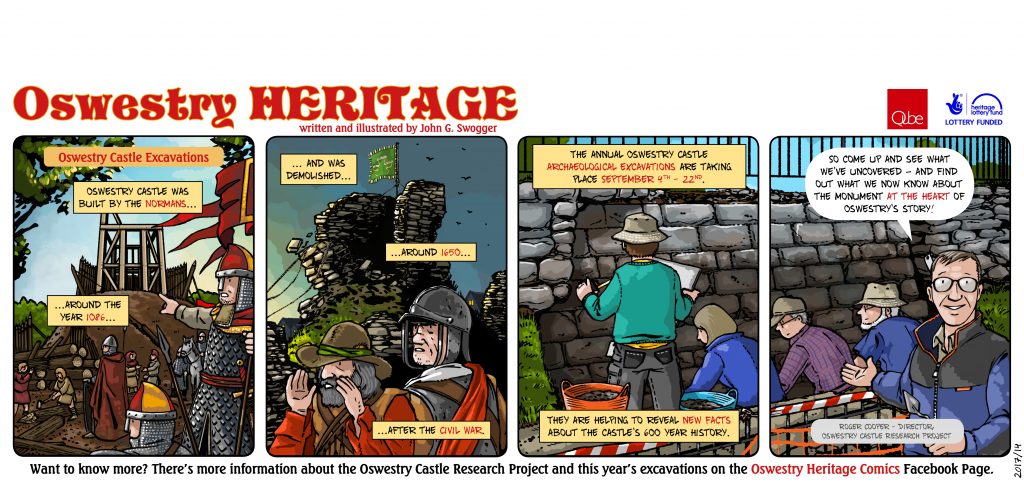

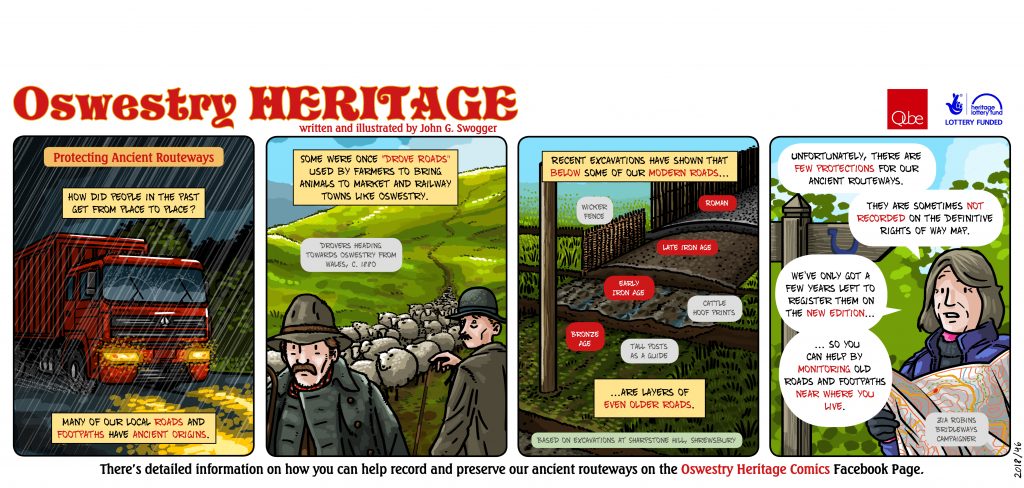

As an archaeological illustrator, I have used informational – or “applied” – comics for the past ten years to explain a wide range of aspects of archaeology: from excavations to landscape surveys, from site preservation to radiocarbon dating, from museum repatriations to community heritage. Comics speak to audiences unfamiliar with archaeology in an engaging and accessible way that makes them ideal for public outreach in a wide range of contexts.

Ceramics, Polity and Comics – Page from the 2015 article in Advances in Archaeological Practice illustrating the “translation” of an article from American Antiquity into a comic. Image courtesy of John Swogger.

Ceramics, Polity and Comics – Page from the 2015 article in Advances in Archaeological Practice illustrating the “translation” of an article from American Antiquity into a comic. Image courtesy of John Swogger.

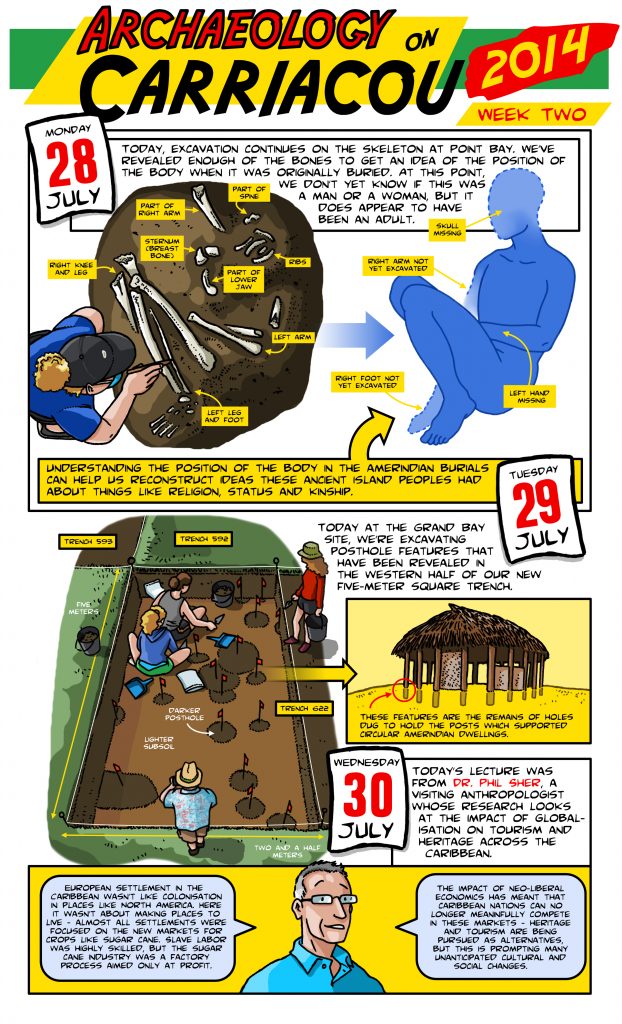

Archaeology on Carriacou – Page from 2011-2014 comic series, published as a set of posters distributed on the island of Carriacou, WI. Image courtesy of John Swogger.

Archaeology on Carriacou – Page from 2011-2014 comic series, published as a set of posters distributed on the island of Carriacou, WI. Image courtesy of John Swogger.

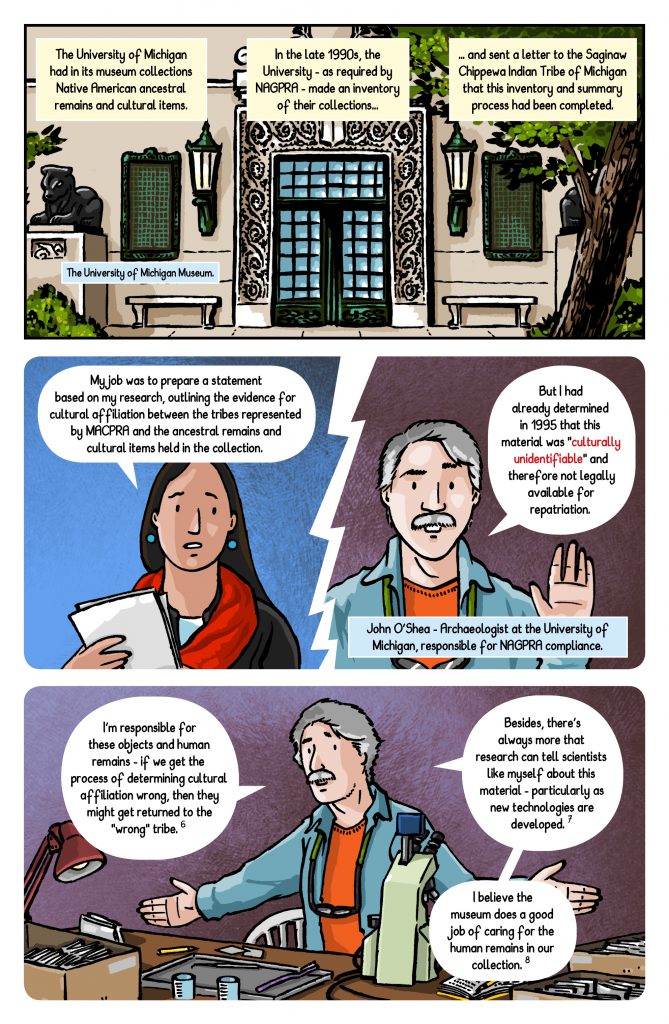

Journeys to Complete the Work – Page from an informational comic about NAGPRA (the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act) aimed at both museums and Native communities explaining how the law works – or, sometimes, doesn’t. Image courtesy of John Swogger.

Journeys to Complete the Work – Page from an informational comic about NAGPRA (the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act) aimed at both museums and Native communities explaining how the law works – or, sometimes, doesn’t. Image courtesy of John Swogger.

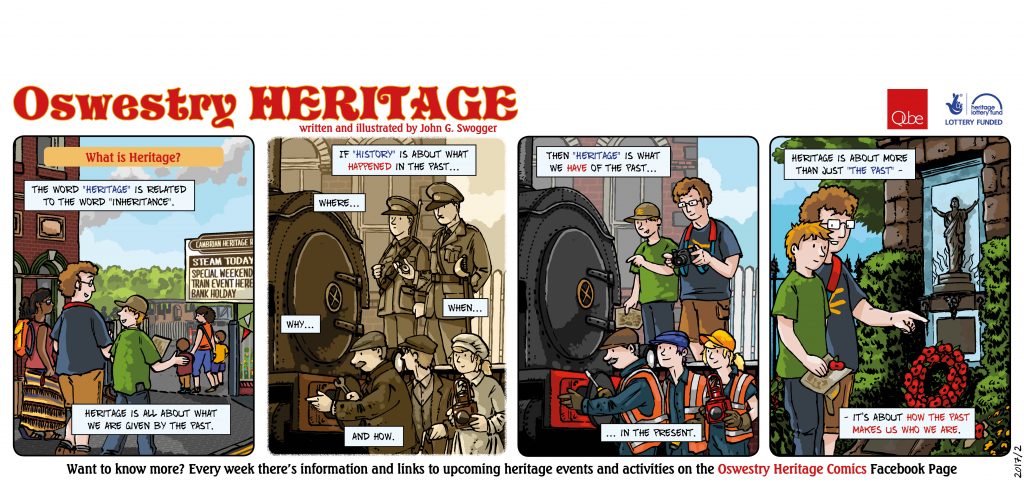

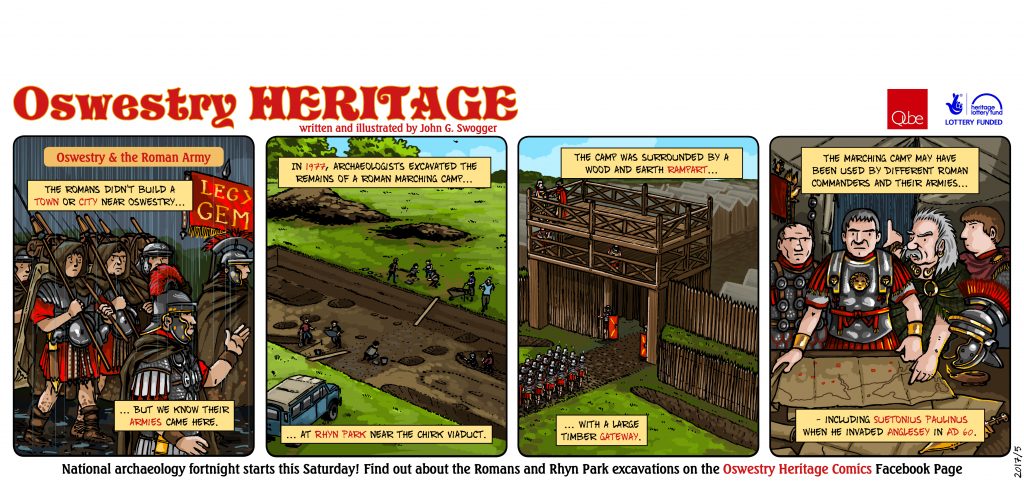

What is Heritage?, Oswestry and the Romans, Oswestry Castle Excavations, Ancient Routeways – Four strips from the series “Oswestry Heritage Comics”, published in the Oswestry & Border Counties Advertizer and on Facebook, Sept. 2016 – June 2018. Project supported by the UK Heritage Lottery Fund. Images courtesy of John Swogger.

Aehtwelighu – Example of a graphic abstract illustrating discussion of cross-border relationships around Offa’s Dyke during the Anglo-Saxon period. Image courtesy of John Swogger.

Aehtwelighu – Example of a graphic abstract illustrating discussion of cross-border relationships around Offa’s Dyke during the Anglo-Saxon period. Image courtesy of John Swogger.

I have created comics about research projects and excavations that have been put up as posters on community noticeboards and local businesses; I have created comics about prehistoric sites that have been used as educational hand-outs for school visits; and I have created comic strips about local heritage, history and archaeology that have been published in local newspapers. Significantly, in all these cases, I have been able to use comics to talk about archaeology in places like shops and supermarkets, schools and local papers – not just museums, visitor centres and archaeological sites. In other words, using comics for public outreach has genuinely allowed me to “reach out” to audiences that might not otherwise engage with archaeological research at all.

But public audiences are only half of the story. I have also used comics to talk to academic audiences and other archaeologists. The principles that make comics so useful for public outreach also make them useful for talking to audiences of one’s own peers. They can be used to quickly explain background concepts that guide research, communicate effectively with staff and students on fieldwork projects, and engage with interdisciplinary scholars. And I have used such comics to create graphic abstracts for academic papers, to report on the results of research projects, to de-complicate highly technical statistical and analytical approaches, and to illustrate multi-layered social and cultural interpretations. They can supply a much-needed narrative and contextual framework to data provided by excavation, lab analysis, and remote sensing – and even technological visualisation techniques such as 3D scanning and LIDAR. I made this argument in an article in the Society for American Archaeology’s journal Advances in Archaeological Practice a few years ago – in the form of a comic, of course!

Critical response to my argument has been positive, but still cautious. “Narrative” still suggests “fiction” to many; “comics” suggest something for children. But modern comics are a sophisticated, mature medium, capable of talking seriously about complex and even contentious issues. Authors like Joe Sacco and Art Spiegelman have used comics to talk about the war in Bosnia and the Holocaust; graphic autobiographers such as Peter Dunlap-Shohl have used comics to recount his diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease. Such narratives are not aimed at children – nor are they dependent upon gratuitous use of “drama” to make their point.

The growing realisation among archaeologists and anthropologists that comics are a sophisticated and nuanced medium for communicating complex information has resulted in a diverse range of follow-on projects and commissions undertaken for academic clients: comics about heritage and immigration in Scandinavia, comics about the repatriation of ancestral remains to Native American nations, comics used to recruit students to university research projects, and comics as graphical abstracts for academic papers. These are comics designed to meet the communication needs of archaeological scholars, demonstrating that – at least in some quarters – the medium’s unique potential for communication beyond public outreach is starting to be recognised.

Although I have worked as an archaeological illustrator all over the world, my background is in the archaeology of the ancient Near East: I was site illustrator for over a decade for the Çatalhöyük Research Project in Anatolia, and have worked on material from Göbekli Tepe, Jericho and have excavated in the Sudan. I am familiar with the issues that make communicating information about the ancient near east to both public and local audiences difficult: the complexity and great time-depth of the archaeology, the convoluted historical, contemporary and political contexts of sites, and the sometimes remote and unfamiliar nature of the way in which archaeological work is carried out.

But it seems to me, too, that the archaeology of the ancient Near East suffers from an additional problem in its public outreach: that of “representational fatigue”. Audiences are perhaps now so used to seeing photographs, paintings, cutaway drawings and 3D models – even filmed reconstructions – of the ancient Near East that I wonder if they have stopped really “seeing” the information they contain. These ways of representing have become so familiar to people that they may think they already know all there is to know about the subject, making it harder to communicate the importance or impact of new research.

Perhaps those who work with this material – whether in the field, in the lab, in the academy or in the museum – could benefit from a new way of taking about their results, process and research? An unexpected way – a way that prompts audiences (both public and academic) to think again about what they think they know about the archaeology of the ancient Near East?

John Swogger is a freelance archaeological illustrator, specialising in finds and reconstruction illustrations for excavation projects, museums and for publication. He was site illustrator for the Çatalhöyük Research Project in Turkey for almost ten years, and now works on sites in the Caribbean, the Pacific, and in Serbia.

Sir Flinders Petrie with his camera. (Petrie Museum archive PMF/WFP1/115/5/2)

Sir Flinders Petrie with his camera. (Petrie Museum archive PMF/WFP1/115/5/2) A ‘battleship curve’ of frequency distribution. (

A ‘battleship curve’ of frequency distribution. (

Journeys to Complete the Work – Page from an informational comic about NAGPRA (the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act) aimed at both museums and Native communities explaining how the law works – or, sometimes, doesn’t. Image courtesy of John Swogger.

Journeys to Complete the Work – Page from an informational comic about NAGPRA (the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act) aimed at both museums and Native communities explaining how the law works – or, sometimes, doesn’t. Image courtesy of John Swogger.

Aehtwelighu – Example of a graphic abstract illustrating discussion of cross-border relationships around Offa’s Dyke during the Anglo-Saxon period. Image courtesy of John Swogger.

Aehtwelighu – Example of a graphic abstract illustrating discussion of cross-border relationships around Offa’s Dyke during the Anglo-Saxon period. Image courtesy of John Swogger.